Whatever will they think of next?

Whatever will they think of next?

Facebook is in court yet again over the Cambridge Analytica scandal, and one of their lawyers made a most revealing assertion :

There is no invasion of privacy at all, because there is no privacy

Now on one level, this is literally true. Facebook's lawyer went on to say that:

Facebook was nothing more than a "digital town square" where users voluntarily give up their private information

The issue is a mismatch in expectations. Users have the option to disclose information as fully public, or variously restricted: only to their friends, or to members of certain groups. The fact that something is said in the public street does not mean that the user would be comfortable having it published in a newspaper, especially if they were whispering into a friend’s ear at the time.

Legally, Facebook may well be in the right (IANAL, nor do I play one on the Internet), but in terms of users’ expectations, they are undoubtedly in the wrong. However, for once I do not lay all the blame on Facebook.

Mechanisation and automation are rapidly subverting common-sense expectations in a number of fields, and consequences can be wide-reaching. Privacy is one obvious example, whether it is Facebook’s or Google’s analysis of our supposedly private conversations, or facial recognition in public places.

For an example of the reaction to the deployment of these technologies, the city of San Francisco, generally expected to be an early adopter of technological solutions, recently banned the use of facial recognition technology. While the benefits for law enforcement of ubiquitous automated facial recognition are obvious, the adoption of this technology also subverts long-standing expectations of privacy – even in undoubtedly public spaces. While it is true that I can be seen and possibly recognised by anyone who is in the street at the same time as me, the human expectation is that I am not creating a permanent, searchable record of my presence in the street at that time, nor that such a record would be widely available.

To make the example concrete, let’s talk for a moment about numberplate recognition. Cars and other motor vehicles have number plates to make them recognisable, including for law enforcement purposes. As technology developed, automated reading of license plates became possible, and is now widely adopted for speed limit enforcement. Around here things have gone a step further, with average speeds measured over long distances.

The problem with automated enforcement is that it is only as good as it is programmed to be. It is true that hardly anybody breaks the speed limit on the monitored stretches of motorway any more – or at least, not more than once. However, there are also a number of negative consequences. Lane discipline has fallen entirely by the wayside since the automated systems were introduced, with slow vehicles cruising in the middle or even outside lanes, with empty lanes on the inside. The automated enforcement has also removed any pressure to consider what is an appropriate speed for the conditions, with many drivers continuing to drive at or near the speed limit even in weather or traffic conditions where that speed is totally unsafe. Finally, there is no recognition that, at 4am with nobody on the roads, there is no need to enforce the same speed limit that applies at rush hour.

Human-powered on-the-spot enforcement – the traffic cop flagging down individual motorists – had the option to modulate the law, turning a blind eye to safe speed and punishing driving that might be inside the speed limit but unsafe in other ways. Instead, automated enforcement is dumb (it is, after all, binary) and only considers the single metric it was designed to consider.

There are of course any number of problems with a human-powered approach as well; members of ethnic or social minorities all have stories involving the police looking for something – anything – to book them for. I’m a straight white cis-het guy, and still once managed to fall foul of the proverbial bored cops, who took my entire car apart looking for drugs (that weren’t there) and then left me by the side of the road to put everything back together. However, automated enforcement makes all of these problems worse.

Facial recognition has documented issues with accuracy when it comes to ethnic minorities and women – basically anyone but the white male programmers who created the systems. If police start relying on such systems, people are going to have serious difficulties trying to prove that they are not the person in the WANTED poster – because the computer says they are a match. And that’s if they don’t just get gunned down, of course.

It is notoriously hard to opt out of these systems when they are used for advertising, but when they are used for law enforcement, it becomes entirely impossible to opt out, as a London man found when he was arrested for covering his face during a facial recognition trial on public streets. A faulty system is even worse than a functional one, as its failure modes are unpredictable.

Systems rely on data, and data storage is also problematic. I recently had to get a government-issued electronic ID. Normally this should be a simple online application, but I kept getting weird errors, so I went to the office with my (physical) ID instead. There, we realised that the problem was with my place of birth. I was born in what was then Strathclyde, but this is no longer an option in up-to-date systems, since the region was abolished in 1996. However, different databases were disagreeing, and we were unable to move forward. In the end, the official effectively helped me to lie to the computer, picking an acceptable jurisdiction in order to move forwards in the process – and thereby of course creating even more inaccuracies and inconsistency. So much for "the computer is always right"… Remember, kids: Garbage In, Garbage Out!

The final argument comes down, as it always does with privacy, to the objection that "there’s nothing to fear if you haven’t done anything wrong". Leaving aside the issues we just discussed around the possibility of running into problems even when you really haven’t done anything wrong, the issue is with the definition of "wrong". Social change is often driven by movement in the grey areas of the law, as well as selective enforcement of those laws. First gay sex is criminalised, so underground gay communities spring up. Then attitudes change, but the laws are still on the books; they just aren’t enforced. Finally the law catches up. If algorithms actually are watching all of our activity and are able to infer when we might be doing something that’s frowned upon by some1, that changes the dynamic very significantly, in ways which we have not properly considered as a society.

And that’s without even considering where else these technologies might be applied, beyond our pleasant Western bubble. What about China, busy turning Xinjiang into an open-air prison for the Uyghur minority? Or "Saudi" Arabia, distributing smartphone apps to enable husbands to deny their wives permission to travel?

Expectations of privacy are being subverted by scale and automation, without a real conversation about what that means. Advertisers and the government stick to the letter of the law, but there is no recognition of the material difference between surveillance that is human-powered, and what happens when the same surveillance is automated.

Photo by Glen Carrie and Bryan Hansonvia Unsplash

And remember, the algorithms may not even be analysing your own data, which you carefully secured and locked down. They may have access to data for one of your friends or acquaintances, and then the algorithm spots a correlation in patterns of communication, and associates you with them. Congratulations, you now have a shadow profile. And what if you are just really unlucky in your choice of local boozer, so now the government thinks you are affiliated with the IRA offshoot du jour, when all you were after was a decent pint of Guinness? ↩

Yesterday was the LinkedIn equivalent of a birthday on Facebook: a new job announcement. I am lucky enough to have well-wishers1 pop up from all over with congratulations, and I am grateful to all of them.

With a new job comes a new title – fortunately one that does not feature on this list of the most ridiculous job titles in tech (although I have to admit to a sneaking admiration for the sheer chutzpah of the Galactic Viceroy of Research Excellence, which is a real title that I am not at all making up).

The new gig is as Director, Field Initiatives and Readiness, EMEA at MongoDB.

Why there? Simply put, because when Dev Ittycheria comes calling, you take that call. Dev was CEO at BladeLogic when I was there, and even though I was a lowly Application Engineer, that was a tight-knit team and Dev paid attention to his people. If I have learned one thing in my years in tech, it’s that the people you work with matter more than just about anything. Dev’s uncanny knack for "catching lightning in a bottle", as he puts it, over and over again, is due in no small part to the teams he puts together around him – and I am proud to have the opportunity to join up once again.

Beyond that, MongoDB itself needs no presentation or explanation as a pick. What might need a bit more unpacking is my move from Ops, where I have spent most of my career until now, into data structures and platforms. Basically, it boils down to a need to get closer to the people actually doing and creating, and to the tools they use to do that work. Ops these days is getting more and more abstract, to the point that some people even talk about NoOps (FWIW I think that vastly oversimplifies the situation). In fact, DevOps is finally coming to fruition, not because developers got the root password, but because Ops teams started thinking like developers and treating infrastructure as code.

Between this cultural shift, and the various technological shifts (to serverless, immutable infrastructure, and infrastructure as code) that precede, follow, and go along with them, it’s less and less interesting to talk about separate Ops tooling and culture. These days, the action is in the operability of development practices, building in ways that support business agility, rather than trying to patch the dam by addressing individual sources of friction as they show up.

More specifically to me, my particular skill set works best in large organisations, where I can go between different groups and carry ideas and insights with me as I go. I’m a facilitator; when I’m doing my job right, I break information out of silos and spread it around, making sure nobody gets stuck on an island or perseveres with some activity or mode of thinking that is no longer providing value to others. Coming full circle, this fluidity in my role is why I tend to have fuzzy, non-specific job titles that make my wife’s eyes roll right back in her head – mirroring the flow I want to enable for everyone around me, whether colleagues, partners, or users.

It’s all about taking frustration and wasted effort out of the working day, which is a goal that I hope we can all get behind.

Now, time to blow away my old life…

Incidentally, this has been the first time I’ve seen people use the new LinkedIn reactions. It will be interesting to watch the uptake of this feature. ↩

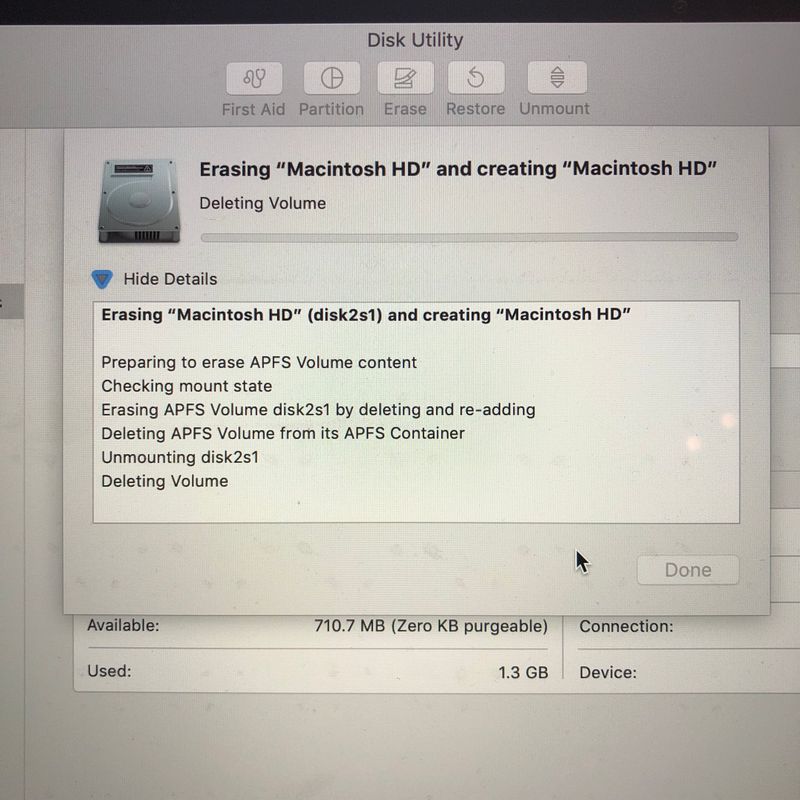

Now here’s an interesting document: "A Measurement Study of Server Utilization in Public Clouds". Okay, it’s from 2011, but otherwise seems legit.

Basically it’s a study of total CPU utilisation in both AWS and Azure (plus a brief reference to GoGrid, a now-defunct provider acquired by Datapipe, who in turn were acquired by Rackspace). The problem is that very few people out there are doing actual studies like this one; it’s mostly comparisons between on-prem and remote clouds, or between different cloud providers, rather than absolute utilisation. However, it’s interesting because it appears to undermine one of the biggest rationales for a move to the cloud: higher server utilisation.

Note that Y-axis: utilisation is peaking at 16%.

The study’s conclusion is as follows:

Apparently, the cost of a cloud VM is so low that some users choose to keep the VM on rather than having to worry about saving/restoring the state.

I wonder if this study would bring any substantially different results if repeated in 2019, with all the talk of serverless and other models that are much less dependent on maintaining state. It is plausible that in 2011 most workloads, even in public clouds, were the result of "lifting and shifting" older architectures onto new infrastructure. The interesting question would be, how many of those are still around today, and how many production workloads have been rearchitected to take advantage of these new approaches.

This is not just an idle question, although there is plenty of scope for snarkily comparing monolithic VMs to mainframes. Cloud computing, especially public cloud, has been able to claim the mantle of Green IT, in large part because of claims of increased utilisation – more business value per watts consumed. If that is not the case, many organisations may want to re-evaluate how they distribute their workloads. Measuring processor cycles per dollar is important and cannot be ignored, but these days the big public cloud providers are within shouting distance of one another on price, so other factors start to enter into the equation – such as environmental impacts.

Image by Samuel Zeller via Unsplash

This story is amazing on so many levels. International banking intrigue on the Eurostar, court cases, huge companies’ deals in jeopardy… It has everything!

The whole story (and associated court case) stems from an episode of shoulder surfing on Eurostar. The Lazard banker working on Iliad’s attempted takeover of T-Mobile US was not paying attention to the scruffy dude sitting beside him on the train. Unfortunately for him, that scruffy dude worked for UBS, and was able to put two and two together (with the assistance of a colleague).

If the Lazard banker had traded on this information, it would have been considered insider trading. However, the judge determined that the information gathered by shoulder-surfing was not privileged, as the UBS banker could not be considered an "insider" (warning, IANAL).

This is why you do not conduct sensitive conversations in trains, airport lounges, and the like. Also, if you are working on information this momentous, one of those screen protectors is probably a worthwhile investment. I have seen and overheard so much information along these lines, although unfortunately I am never in a position to take advantage of any of it.

As usual, humans are the weakest link in any security policy. This is particularly humorous since today I found that, at some point over the Easter break, corporate IT has disabled iCloud Drive on our Macs. Dropbox and my personal login to Google Drive / File Stream / whatever-it’s-called-this-week all still work though…

A particularly paranoid form of security audit would include shadowing key employees on their commutes or business travel to see how well company information is protected. But probably not. It’s much easier just to install annoying agents on everybody’s machines, tick that box, and move on.

Image is a still from this excellent video by ENISA.

There has been a bit of a Twitterstorm lately over an article (warning: Business Insider link), in which the executive managing editor of Insider Inc., who "has hired hundreds of people over 10 years", describes her "easy test to see whether a candidate really wants the job and is a 'good egg'": Did they send a thank-you email?

This test has rightly been decried as a ridiculous form of gatekeeping, adding an unstated requirement to the hiring process. Personally I would agree that sending a thank-you note is polite, and also offers the candidate an opportunity to chase next steps and confirm timelines. However, I would not rule out a candidate just because I didn’t receive such a note – and I have also received overly familiar notes which actively put me off those candidates.

The reason these unstated rules are so important is because of the homogenising effect that they tend to have. Only people who are already familiar with "how things are done" are going to be hired or have a career, perpetuating inequality.

This effect has been borne out in a study recently summarised in The Atlantic:

The name that we gave to the culture there was "studied informality" —nobody wore suits and ties, nobody even wore standard business casual. People were wearing sneakers and all kinds of casual, fashionable clothes. There was a sort of "right" way to do it and a "wrong" way to do it: A number of people talked about this one man — who was black and from a working-class background — who just stood out. He worked there for a while and eventually left. He wore tracksuits, and the ways he chose to be casual and fashionable were not the ways that everybody else did.

There were all kinds of things, like who puts their feet up on the table and when they do it, when they swear — things that don’t seem like what you might expect from a place full of high-prestige, powerful television producers. But that was in some ways, I think, more off-putting and harder to navigate for some of our working-class respondents than hearing "just wear a suit and tie every day" might have been. The rules weren't obvious, but everybody else seemed to know them.

I have seen this mechanism in action myself – in much more trivial circumstances, I hasten to add.

One day I was in the office and unexpectedly had to attend a customer meeting at short notice. I was wearing a shirt and a jacket, but I had no tie and had on jeans and sneakers. I apologised to the customer, and there was no issue.

On the other hand, it happened to me to visit a "cool" cloud company in my normal business warpaint, and was told in the lift to remove my tie as "otherwise they won't listen to you"…

Let's not even get into the high-school sociological aspects of people wearing the wrong shoes. Distinctions between suits are subtle, but it's obvious when someone is wearing cheap sneakers versus branded ones.

Instead of unstated and unspoken implicit rules like these, it is much better to have clear and explicit ones, which everyone can easily conform to, such as wearing a suit and tie (or female equivalent – and yes, I know that is its own minefield):

In fact, suits & ties are actually the ultimate nerd apparel. You have to put some effort into shopping, sure, and they tend to cost a bit more than a random vendor T-shirt and ancient combats, but the advantage is that you can thereafter completely forget about wondering what to wear. You can get dressed in the dark and be sure that the results will be perfectly presentable. If you want you can go to a little bit more effort and inject some personality into the process, but the great thing is that you don’t have to. By wearing a suit & tie, you lead people to pay attention to what you say and do, not to what you are wearing. And isn’t that the whole point?

Another unstated gatekeeping mechanism is "culture fit". This is all but explicitly saying "I only want to hire people from my social/class background, and will exclude candidates with a different background".

Uhoh, This content has sprouted legs and trotted off.

Here I do think there is some subtlety that is worth exploring. I attempted to respond to the tweet above, but expressed myself poorly (always a risk on Twitter) and did not communicate my point well.

First of all, there is a collision here between "is this person like me" and "would I want to spend time socially with this person". I feel that the sort of people who do this implicit gatekeeping would indeed only want to associate with people from the same background as them, and so this question becomes problematic in that context.

However, some of the reactions to the original tweet appeared to me to take the objection too far, stating that looking for social compatibility at work was ipso facto wrong. Having made several friends through work, I disagree with that view. In fact, I would go so far as to say that my work friendships are influenced in no small part by the fact that my friends are good at their job, and the factors that make them good professionals are also the factors that make them good friends: intelligent, trustworthy, honest, high EQ, and so on.

The correlation is of course not 1:1; I have known many successful and effective professionals who are not my friends. However, by excluding these factors entirely from the decision matrix, I see a particular failure mode, namely the fallacy that only people with abrasive personalities are effective, and therefore all people with abrasive personalities are good hires because they will be effective. It is not surprising that those sorts of people do not make friends at work.

The particular weight placed upon these factors may vary depending on which role in an organisation is being looked at. Customer-facing positions, where it is important to establish and maintain a rapport, may place particular emphasis on high EQ, for instance.

Somehow it never seems to cut the other way: “sorry, we have a diverse bunch of interesting people with cool hobbies, while you have the personality of wet cardboard and suck the will to live out of anyone nearby”. Culture fit tends to mean everyone has the culture of yogurt.

— Dominic 🇪🇺🇺🇦🏳️🌈 (@dwellington) April 10, 2019

Of course the opposite failure mode is the one where everybody looks the same, dresses the same, went to the same schools – and only hires people exactly like them. This is why explicit rules and failsafes in the process are important, to avoid "culture fit" becoming – or remaining, if we’re honest – a fig leaf used to cloak institutional racism and classism.

As ever, the devil is in the details.

Images by Kelly Sikkema and Hunters Race via Unsplash

Having now put the first 2000km on my Giulia, across city, motorway, and twisty Alpine road, here are some first impressions and comparisons with the late lamented Beast.

Quite apart from all the differences inherent in going from a lardy SUV to a lithe sports saloon that weighs about as much as one of my old Cayenne’s doors, there is also more than a decade of evolution separating the two cars, so there are all sorts of changes to take into account. Overall though I am just so happy with my choice; the thing looks just perfect, subtle but aggressive, a brawler in an impeccably tailored Italian suit. The gamble with the paint colour paid off, despite looking nothing like the picture in the online configurator! It shifts between grey and blue, with bronze accents in the sunlight, and looks far better than that description – although the full effect doesn’t quite come across in pictures.

The Giulia also manages to pull off that trick that 911s have of feeling special even at parking speeds, and keeps it up all the way to the rev limiter – not that I have explored that too much yet, as I wanted to run the motor in somewhat gently. The good feeling is due in no small part to the mass of the engine being entirely behind the line of the front axle, contributing to that perfect weight distribution.

The lightness and sensitivity of the steering are a huge part of this "specialness", but it’s a feeling that is woven throughout the car, from the way the instruments are angled towards the driver, to the seats that offer a perfectly judged combination of comfort and firm bolsters holding you in place. The DNA modes also help, with a switch into Dynamic feeling like a shot of adrenaline straight into the driver’s veins, vision turning red at the edges in sync with the instruments.

I did miss the air suspension from the Beast on some of the broken cobbled surfaces in Milan, but apart from that I far prefer the Giulia’s sporty setup, which even in standard mode appears to have deep-seated religious objections to any roll in the body. In sport mode it adds a well-judged firmness without becoming crashy – in other words, it’s still comfortable on the straights, and then sends the car around corners absolutely flat.

Mostly my impressions from the test drive were confirmed in spades. It’s a taut, agile car; the engine is very willing even in automatic mode, but also rewards use of the paddles. A four-cylinder engine is inherently never going to sound as good as a V8, but the Beast was not especially vocal, while I suspect the Alfa team had a few meetings with the team that tunes the exhausts over at Abarth. It’s not nearly as bombastic as those little 500s, but the Giulia’s twin exhausts still manage to sound pretty fruity when you push on a bit.

One place where the Chrysler part of Fiat-Chrysler shows through is the very American-sounding beep which goes off if you change lanes without indicating. The lane departure warning can easily be turned on and off from a button on the end of one of the stalks, which is a very Italian touch that is convenient on a twisty mountain road where you're frequently crossing back and forth across the centre line.

There is also radar cruise control, which does a pretty decent job of keeping its distance from traffic. It could be better, as while the distance is adjustable, even the minimum distance is still quite far away, especially by the standards of Italian motorways. The system is also quite eager to drop a cog to accelerate back up to speed, which is not necessary at all. When I’m on the cruise control, by definition I’m in no hurry! Anyway, this feature is mostly helpful, but only with light traffic. In even moderate traffic, it’s too eager to back off, then surge back up to speed – not very relaxing.

The same radar sensor also drives a forward collision warning system, which, yes, I have already heard triggered. I was already braking, but it automatically activated the hazard lights when the warning fired, which could be useful when doing a full emergency stop.

The dashboard screen is gorgeous but not touch sensitive, which is initially disconcerting when trying to navigate CarPlay. After a month of use I think I actually prefer doing it through the clickwheel, as it’s much easier to get things done without taking my eyes off the road. The usual steering wheel buttons also help, with play/pause, cue, and volume buttons all present and correct. The other two ICE-related buttons are used to hang up on a call, and to trigger Siri, so I don’t really miss touching the screen at all.

On that note, it is so good to have physical controls in the cabin for functions like climate control. I don’t need to take my eyes off the wheel to make it cooler or warmer; there is a lovely tactile wheel that I can twist around a little or a lot, and know right away whether my action was registered. There’s also a physical control between the seats for the ICE, with volume, play/pause, forward/back, and screen off functions – very useful for the passenger, while the driver is probably best served using the steering wheel controls.

Bottom line, I absolutely love my Giulia. If you’re in the market for something similar, I highly recommend it. If you’re not up for the Veloce setup that I got (or for the full-beans Quadrifoglio monster!), you can get most of the same goodness on the Super, with the same two-litre motor in a milder 200bhp tune. Take a test drive, you won’t regret it!