In Apple-watching circles, there has long been some significant frustration about Apple's App Store policies. Whether it's the opaque approvals process, the swingeing 30% cut that Apple takes out of any purchase, or the restrictions on what types of apps and pricing models are even allowed, developers are not happy.

It was not always this way: when the iPhone first launched, there was no App Store. Everying was supposed to be done with web apps. Developers being developers, people quickly worked out how to "jailbreak" their iPhones to install their own apps, and a thriving unofficial marketplace for apps sprang up. Apple, seeing this development taking place out of their control, relented and launched an official App Store. The benefit of the App Store was that it would do everything for developers: hosting, payment process, a searchable catalogue, everything. Remember, the App Store launched in 2008, when all of that was quite a bit harder than it is today, and would have required developers to make up-front investments before even knowing whether their apps would take off — without even thinking about free apps.

With the addition of in-app purchase (IAP) the next year, and subscriptions a couple of years after that, most of the ingredients were in place for the App Store as we know it today. The App Store was a massive success, trumpeted by Apple at every opportunity. In January, Apple said that it paid developers $60 billion in 2021, and $260 billion since the App Store launched in 2008. Apple also reduced its cut from 30% to 15%, initially for the second year of subscriptions, but later for any developer making less than $1M per year in the App Store.

What's Not To Like?

This all sounds very fine, but developers are up in arms over Apple's perceived high-handed or even downright rapacious behaviour when it comes to the App Store. Particular sticking points are requirements that apps in the App Store use only Apple's payment system, and that apple’s own in-app purchasing mechanism be used for any digital experience offered to groups of people. The first requirement touched off a lawsuit from Epic, who basically wanted to have their own private store for in-game purchases, and the second resulted in some bad press early in the pandemic when Apple started doing things like chasing fitness instructors who were providing remote classes while they were unable to offer face-to-face sessions.

The bottom line is that many of these transactions simply do not have a 30% margin in the first place, let alone the ability to still make any profit after giving Apple a 30% (or even a 15%) cut. This might seem to be a problem for developers, but not really for anyone else — but what gave this issue resonance beyond the narrow market of iOS developers is that the world has moved on since 2008.

Hosting an app and setting up payment for it is easy and cheap these days, thanks to the likes of AWS and Stripe. Meanwhile, App Store review is capricious, while also allowing through all sorts of scams, generally based on subscriptions — what is becoming known as fleeceware.

The long and the short of it is that public opinion has shifted against Apple, with proceedings not just in the US, but in Korea, Japan, and the Netherlands too. Apple are being, well, Apple, and refusing to budge except in the most minor and grudging ways.

Here is my concern, though: this situation is being looked at as a simple conflict between Apple and developers. In all the brouhaha, nobody ever mentions another very important perspective: what do users want?

Won't Somebody Think Of The Users?

Developers rightly point out that the $260B that Apple trumpeted having paid them was money generated by their apps, not Apple's generosity, and that a big part of the reason users buy Apple's devices is the apps in the App Store. However, that money was originally paid by users, and we also have opinions about how the App Store should work for our needs and purposes.

First of all, I want all of the things that developers hate. I want Apple's App Store to be the only way of getting apps on iPhones, I want all subscriptions to be in the App Store, and I want Apple's IAP to be the only payment method. These are the factors that make users confident in downloading apps in the first place! Back when I had a Windows machine, it was just accepted that every twelve months or so, you'd have to blow away your operating system and reinstall it from scratch. Even if you were careful and avoided outright malware, bloat and cruft would take over and slow everything to a crawl — and good luck ever removing anything. Imagine a garden that you weed with a flamethrower.

The moment Apple relaxed any of the restrictions on app installation and payment, shady developers would stampede through — led by Epic and Facebook, who both have form when it comes to dodgy sideloading. It doesn't matter what sort of warnings Apple put into iOS; if that were to become how people get their Fortnight or their WhatsApp, they would tap through any number of dialogues without reading them, just as fast as they can tap. And once that happens, all bets are off. Subscriptions to Epic's games or to whatever dodgy thing in Facebook's platform would not be visible in users' App Store profiles, making it all too easy for money to be drained out, through forgetfulness and invisibility if not outright scams.

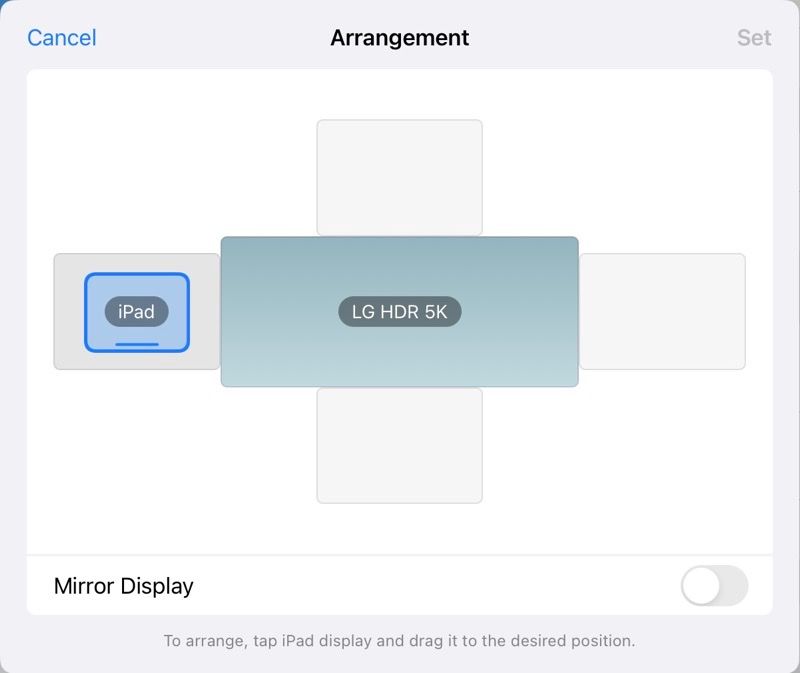

Other Examples: The Mac

People sometimes bring up the topic of the Mac App Store, which operates along the same notional lines as the iOS (and iPadOS) App Store, but without the same problems. The Mac App Store is actually a great example, but not for the reasons its proponents think. On the Mac, side-loading — deploying apps without going through the Mac App Store — is very much a thing, and in fact it is a much bigger delivery channel than the Mac App Store itself. The problem is that it is also correspondingly harder to figure out what is running on a Mac, or to remove every trace of an app that the user no longer wants. It's nowhere near as bad as Windows, to be clear, but it's also not as clean-cut as iOS, where deleting an app's icon means that app is gone, no question about it.

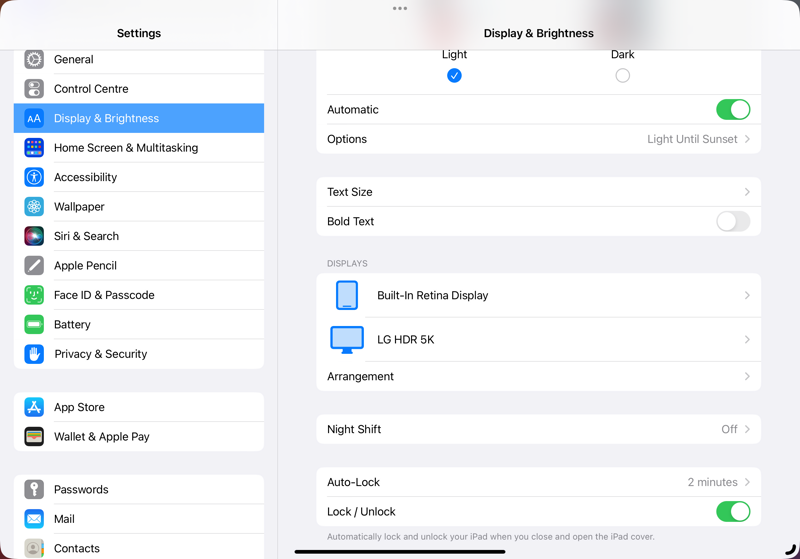

On the Mac, technical users have all sorts of tools to manage this situation, and that extra flexibility also has many other benefits, making the Mac a much more capable platform than iOS (and iPadOS — sigh). But many more people own iPhones and iPads than own Macs, and they are comfortable using those devices precisely because of the sandboxed nature of the experience. My own mother, who used to invite me to lunch and then casually mention that she had a couple of things she needed me to do on the computer, is fully independent on her iPad, down to and including updates to the operating system. This is because the lack of accessible complexity gives her confidence that she can't mess something up by accident.

More Examples: Google

Over the pandemic, I have had the experience of comparing Google's and Apple's family controls, as my kids have required their own devices for the first time for remote schooling. We have a new Chromebook and some assorted handed-down iPads and iPhones (without SIM cards). The Google controls are ridiculously coarse-grained and easily bypassed — that is, when they are not actively conflicting with each other: disabling access to YouTube breaks the Google login flow… In contrast, Apple lets me be extremely granular in what is allowed, when it is allowed, and for how long. Once again, this is possible because of Apple's end-to-end control: I can see what apps are associated with each kid's account, and approve or decline them, enforce limits, and so on. I don't want to have to worry that they will subscribe to a TikTok creator or something, outside the App Store, and drain my credit card, possibly with no way to cancel or get a refund.

What Now?

Good developers like Marco Arment want to build a closer relationship with customers and manage that process themselves. I do trust Marco to use those tools ethically — but I don't trust Mark Zuckerberg with the same tools, and this is an all-or-nothing decision. If it's the price it takes to keep Mark Zuckerberg out of my business, then I'd rather have the status quo.

All of that said, I do think Apple are making things harder on themselves. Their unbending attitude in the face of developers' complaints is not serving them well, whether in the court of public opinion or in the court of law. I do hope that someone at Apple can figure out a way to give enough to developers to reduce the noise — cut the App Store take, make app review more transparent, enable more pricing models, perhaps even refunds with more developer input, whatever it takes. There are also areas where the interests of developers and users are perfectly aligned: search ads in the App Store are gross, especially when they are allowed against actual app names. It's one thing (albeit still icky) to allow developers to pay to increase their ranking against generic terms, like "podcast player"; it's quite another to allow competing podcast players to advertise against each other by name. Nobody is served by that.

If Apple does not clear up this mess themselves, the risk is that lawmakers will attempt to clear it up for them. This could go wrong in so many ways, whether it's specific bad policies (sideloading enforced by law), or a patchwork of different regulations around the world, further balcanising the experience of users based on where they happen to live.

Everyone — Apple, developers, and users — want these platforms to (continue to) succeed. For that to happen, Apple and developers need to talk — and users' concerns must be heard too.

🖼️ Photos by Neil Soni on Unsplash