Last time I wrote about ChatGPT, I was pretty negative. Was I too harsh?

The reason I was so negative is that many of the early demos of ChatGPT focus on feats that are technically impressive ("write me a story about a spaceman in the style of Faulkner" or whatever), but whose actual application is at best unclear. What, after all, is the business model? Who will pay for a somewhat stilted story written by a bot, at least once the novelty value wears off? Actual human writers are, by and large, not exactly rolling in piles of dollars, so it's not as if there is a huge profit opportunity awaiting the first clever disrupter — quite apart from the moral consequences of putting a bunch of humans out of a job, even an ill-paying one.

Instead, I wanted to think about some more useful and positive applications of this technology, ones which also have the advantage that they are either not being done at all today, or can only be done at vast expense and not at scale or in real time. Bonus points if they avoid being actively abusive or enabling ridiculous grifts and rent-seeking. After all, with Microsoft putting increasing weight behind Open AI, it's obvious that smart people smell money here somewhere.

Summarise Information (B2C)

It's more or less mandatory for new technology to come with a link to some beloved piece of SF. For once, this is not a Torment Nexus-style dystopia. Instead, I'm going right to the source, with Papa Bill's Neuromancer:

"Panther Moderns," he said to the Hosaka, removing the trodes. "Five minute precis."

"Ready," the computer said.

Here's a service that everyone wants, as evidenced by the success of the "five-minute explainer" format. Something hits your personal filter bubble, and you can tell there is a lot of back story; battle lines are already drawn up, people are several levels deep into their feuds and meta-positioning, and all you want is a quick recap. Just the facts, ma'am, all sorts of multimedia, with a unifying voiceover, and no more than five minutes.

There are also more business-oriented use cases for this sort of meta-textual analysis, such as "compare this quarter's results with last quarter's and YoY, with trend lines based on close competitors and on the wider sector". You could even link with Midjourney or Stable Diffusion to graph the results (without having to do all the laborious cutting and pasting to get the relevant numbers into a table first, and making sure they use the same units, currencies, and time periods).

Smarter Assistants (B2C)

One of the complaints that people have about voice assistants is that they appear to have all the contextual awareness of goldfish. Sure, you can go to a certain amount of effort to get Siri, Alexa, and their ilk to understand "my wife" without having to use the long-suffering woman's full name and surname on each invocation, but they still have all the continuity of an amnesiac hamster if you try to continue a conversation after the first interaction. Seriously, babies have a far better idea of object persistence (peekaboo!). The robots simply have no way of keeping context between statements, outside of a few hard-coded showcase examples.

Instead, what we want is precisely that continuity: asking for appointments, being read a list, and then asking to "move the first one to after my gym class, but leave me enough time to shower and get over there". This is the sort of use case that explains why Microsoft is investing so heavily here: they are so far behind otherwise that why not? Supposedly Google has had this tech for a while and just couldn't figure out a way to introduce it without disrupting its cash-cow search business. And Apple never talks about future product directions until they are ready to launch (with the weird exception of Project Titan, of course), so it may be that they are already on top of this one. Certainly it was almost suspicious how quickly Apple trotted out specific support for Stable Diffusion.

Tier Zero Support (B2B)

Back in the day, I used to work in tech support. The classic division of labour in that world goes something like this:

- Tier One, aka "the phone firewall": people who answer telephone or email queries directly. Most questions should be solved at this level.

- Tier Two: these are more expert people, who can help with problems which cannot be resolved quickly at Tier One. Usually customers can’t contact Tier Two directly; their issues have to be escalated there. You don't want too many issues to get to this level, because it gets expensive.

- Tier Three: in software organisations, these are usually the actual engineers working on the product. If you get to Tier Three, your problem is so structural, or your enhancement request is sufficiently critical, that it's no longer a question of helping you to do something or fixing an issue, but changing the actual functioning of the product in a pretty major way.

Obviously, there are increasing costs at each level. A problem getting escalated to Tier Two means burning the time of more senior and expert employees, who are ipso facto more expensive. Getting to Tier Three not only compounds the monetary cost, but also adds opportunity costs: what else are those engineers not doing, while they work on this issue? Therefore, tech support is all about making sure problems get solved at the lowest possible tier of the organisation. This focus has the happy side-effect of addressing the issue faster, and with fewer communications round-trips, which makes users happier too.

It's a classic win-win scenario — so why not make it even better? That's what the Powers That Be decided to do where I was. They added a "Tier Zero" of support, that was outsourced (to humans), with the idea that they would address the huge proportion of queries that could be answered simply by referring to the knowledge base.

So how did this go? Well, it was such a disaster that my notoriously tight-fisted employers ended up paying to get out of the contract early. But could AI do better?

In theory, this is not a terrible idea. Something like ChatGPT should be able to answer questions based on a specific knowledge base, including past interactions with the bot. Feed it product docs, FAQs, and forum posts, and you get a reasonable approximation of a junior support engineer. Just make sure you have a way for a user to pull the rip-cord and get escalated to a human engineer when the bot gets stuck, and why not?

One word of caution: the way I moved out of tech support is that I would not only answer the immediate question from a customer, but I would go find the account manager afterwards and tell them their customer needed consulting, or training, or more licenses, or whatever it was. AI might not have the initiative to do that.

Another drawback: it's hard enough to give advice in a technical context, but at least there, a command will either execute or not; it will give the expected results, or not (and even then, there may be subtle bugs that only manifest over time). Some have already seized on other domains that feature lots of repetive text as opportunities for ChatGPT. Examples include legal contracts, and tax or medical advice — but what about plausible-but-wrong answers? If your chatbot tells me to cure my cancer with cleanses and raw vegetables, can I (or my estate) sue you for medical malpractice? If your investor agreement includes a logic bug that exposes you to unlimited liability, do you have the right to refuse to pay out? Fun times ahead for all concerned.

Formulaic Text (B2B)

Another idea for automated text generation is to come up with infinite variations on known original text. In plain language, I am talking about A/B testing website copy in real time, rewriting it over and over to entice users to stick around, interact, and with any luck, generate revenue for the website operators.

Taken to the extreme, you get the evil version, tied in with adtech surveillance to tweak the text for each individual visitor, such that nobody ever sees the same website as anyone else. Great for plausible deniability, too, naturally: "of course we would never encourage self-harm — but maybe our bot responded to something in the user's own profile…".

This is the promise of personalised advertising, that is tweaked to be specifically relevant to each individual user. I am and remain sceptical of the data-driven approach to advertising; the most potent targeted ads that I see are the same examples of brand advertising that would have worked equally well a hundred years ago. I read Monocle, I see an ad for socks, I want those socks. You show me a pop-up ad for socks while I am trying to read something unrelated, I dismiss it so fast that I don't even register that it's trying to sell me socks. It's not clear to me that increasing smarts behind the adtech will change the parameters of that equation significantly.

De-valuing Human Labour

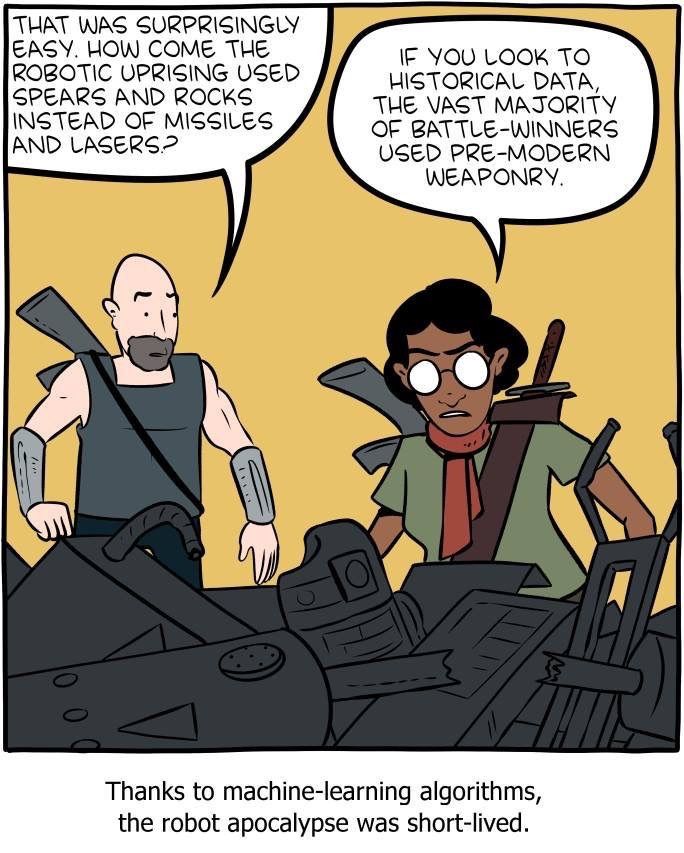

These are the use cases that seem to me to be plausible and defensible. There will be others that have a shorter shelf life, as illustrated in Market For Lemons:

What happens when every online open lobby multiplayer game is choked with cheaters who all play at superhuman levels in increasingly undetectable ways?

What happens when, from the perspective of the average guy, "every girl" on every dating app is a fiction driven by an AI who strings him along (including sending original and persona-consistent pictures) until it's time to scam money out of him?

What happens when, from the perspective of the average girl, "every guy" on the internet has become weirdly dismissive and hostile, because he's been conditioned to think that any girl that seems interested in him must be fake and trying to scam money out of him?

What happens when comments sections on every forum gets filled with implausibly large consensus-building hordes who are able to adapt in real time and carefully slip their brigading just below the moderator's rules?

What these AI-enabled "growth hacks" boil down to is taking advantage of a market that has already outsourced labour and creativity to (human) non-employees: multiplayer games, user-generated content, and social media in general. Instead of coming up with a storyline for your game, why not just make users pay to play with each other? Instead of paying writers, photographers, and video makers, why not just let them upload their content for free? And with social media, why not just enable users to live vicariously through the fantasy lives of others, while shilling them products that promise to let them join in?

Now computers can deliver against those savings even better — but only for a short while, until people get bored of dealing with poor imitations of fellow humans. We old farts already bailed on multiplayer games, because it's no fun spending my weekly hour of gaming just getting ganked repeatedly by some twelve-year-old who plays all day. Increasingly, I bailed on UGC networks: there is far more quantity than quality, and I would rather pay for a small amount of quality than have to sift through the endless quantity.

If the pre-teen players with preternaturally accurate aim are now actually bots, and the AI-enhanced influencers are now actually full-on AIs, those developments are hardly likely to draw me back to the platforms. Any application of AI tech that is simply arbitrage on the cost of humans without factoring in other aspects has a short shelf life.

Taken to its extreme, this trend leads to humans abdicating the web entirely, leaving the field to AIs creating content that will be ranked by other AIs, and with yet more AIs rewarding the next generation of paperclip-maximising content-producing AIs. A bleak future indeed.

So What's Next?

At this point, with the backing of major players like Microsoft and Apple, it seems that AI-enabled products are somewhat inevitable. What we can hope for is that, after some initial over-excitement, we see fewer chatbot psychologists, and more use cases that are concrete, practical, and helpful — to humans.

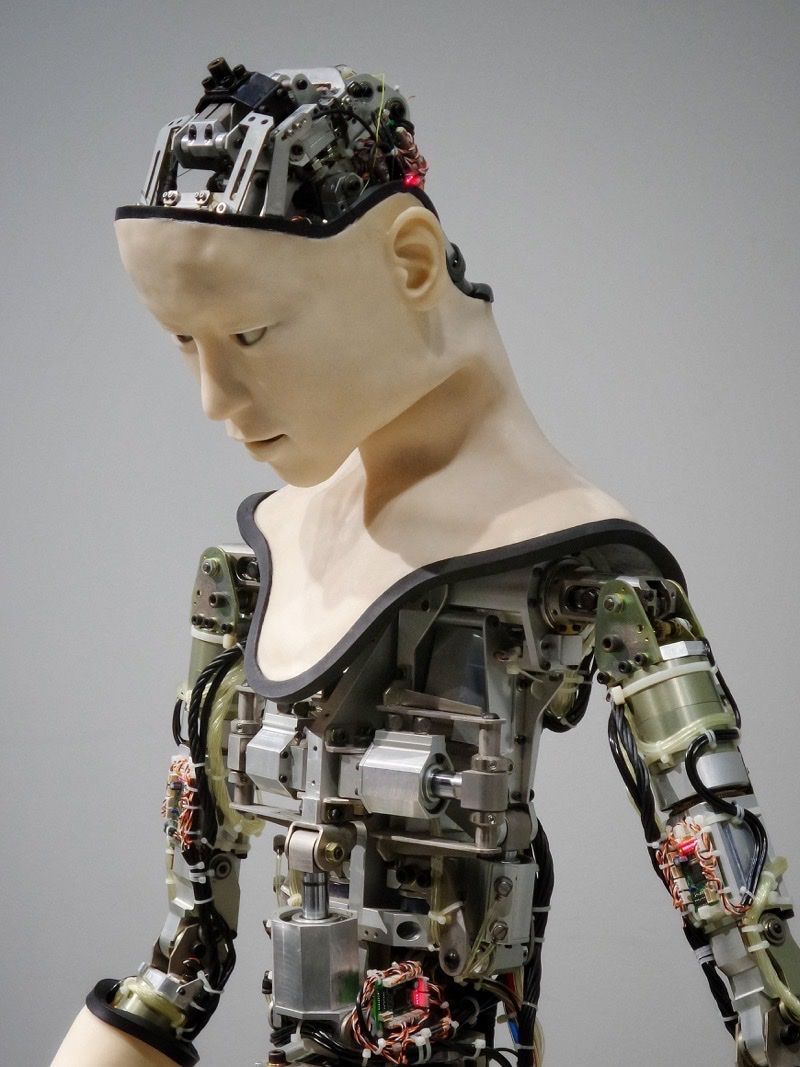

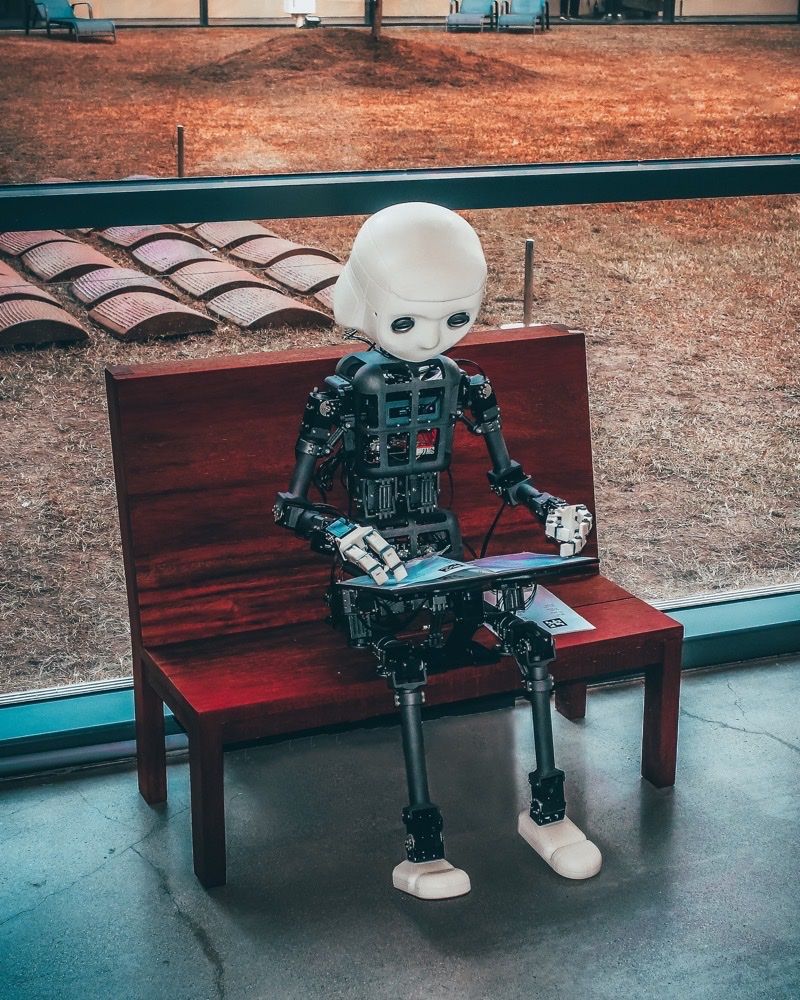

🖼️ Photos by Andrea De Santis and Charles Deluvio on Unsplash