At this time of year, with the nights drawing in, thoughts turn inevitably to… AWS' annual Las Vegas extravaganza, re:Invent. This year I'm attending remotely again, like it's 2020 or something, which is probably better for my liver, although I am definitely feeling the FOMO.

Day One: Adam Selipsky Keynote

I skipped Monday Night Live due to time zones, but as usual, this first big rock on the re:Invent calendar is a barrage of technical updates, with few hints of broader strategy. That sort of thing comes in the big Tuesday morning keynote with Adam Selipsky.

Last year was his first time taking over after Andy Jassy's ascension to running the whole of Amazon, not just AWS. This year’s delivery was more polished, plus it looks like we have seen the last of the re:Invent House Band. Adam Selipsky himself though was still playing the classics, talking up the benefits of cloud computing for cost savings and using examples such as Carrier or Airbnb to allude to companies' desire to be agile with fewer resources.

Still, it's a bit of a double-take to hear AWS still talking about cloud migration in 2022 — even if, elsewhere in Vegas, there was a memorable endorsement of migration to the cloud from Ukraine's Minister for Digital Transformation. Few AWS customers have to contend with the sorts of stress and time pressure that Mykhailo Fedorov did!

In the keynote, the focus was mostly on exhortations to continue investing in the cloud. I didn't see Andy Jassy's signature move of presenting a slide that shows cloud penetration as still being a tiny proportion of the market, but that was definitely the spirit: no reason to slow down, despite economic headwinds; there's lots more to do.

Murdering the Metaphors

We then got to the first of various metaphors that would be laboriously and at length tortured to breaking point and beyond. The first was space exploration, and admittedly there were some very pretty visuals to go with the point being belaboured: namely, that just like images captured in different wavelengths show different data to astronomers, different techniques used to explore data can deliver additional results.

There were some good customer examples in this segment: Expedia Group making 600B predictions on 70 Petabytes of data, and Pinterest storing 1 Exabyte of data on S31. That sort of scale is admittedly impressive, but this was the first hint that the tempo of this presentation would be slower, with a worse ratio of content to time than we had been used to in the Jassy years.

Tools, Integration, Governance, Insights

This led to a segment on the right tools, integration, and governance for working with data, and the insights that would be possible. The variety of tools is something I had focused on in my report from re:Invent 2021, in which I called out AWS' "one database engine for each use case" approach and questioned whether this was what developers actually wanted.

Initially, it seemed that we were getting more of the same, with Amazon Aurora getting top billing. The metrics in particular were very much down in the weeds, mentioning that Aurora offered 1/10 the cost of commercial DBMS, while also having up to 3x performance of PostgreSQL and 5x the performance of MySQL2.

We then heard about how customers also need analytics tools, not just transactional ones, such as EMR, MSK, and Redshift for high performance on structured data - 5x better price performance than "other cloud data warehouses" (a not-particularly-veiled dig at Snowflake, here — more of a Jassy move, I felt).

The big announcement in this section was OpenSearch Serverless. This launch means that AWS offers serverless options for all of its analytics services. According to Selipsky, "no-one else can say that". However, it is worth checking the fine print. In common with many "serverless" offerings, OpenSearch Serverless has a minimum spend of 4 OCUs — or $700 in real money. Scaling to zero is a key requirement and expectation of serverless, so it is disappointing to see so many offerings like this one that devolve to elastic scalability on top of a fixed base. Valuable, to be sure, but not quite so revolutionary.

ETL Phone Home

Then things got interesting.

Adam Selipsky made an example of a retail company running its operations on DynamoDB and Aurora and needing to move data to Redshift for analysis. This is exactly the sort of situation I decried in last year's report for The New Stack: too many single-purpose databases, leaving users trying to copy data back and forth, with the attendant risk of loss of control over their data.

It seems that AWS product managers had been hearing the same feedback that I had, but instead of committing to one general-purpose database, they are doubling down on their best-of-breed approach. Instead, they enabled federated query in Redshift and Athena to query other services — including third-party ones.

The big announcement was zero-ETL integration between Aurora and Redshift. This was advertised as being "near real time", with latency measured in seconds — good enough for most use cases, although something to be aware of for more demanding situations. The integration also works with multiple Aurora instances all feeding into one Redshift instance, which is what you want. Finally, the integration was advertised as being "all serverless", scaling up and down in response to data volume.

Take Back Control

So that's the integration — but that only addresses questions of technical complexity and maybe cost of storage. What about governance? Removing the need for ETL from one system into another does remove one big issue, which is the creation of a second copy of the data without the access controls and policy enforcement applied to the original. However, there is still a need to track metadata — data about the data itself.

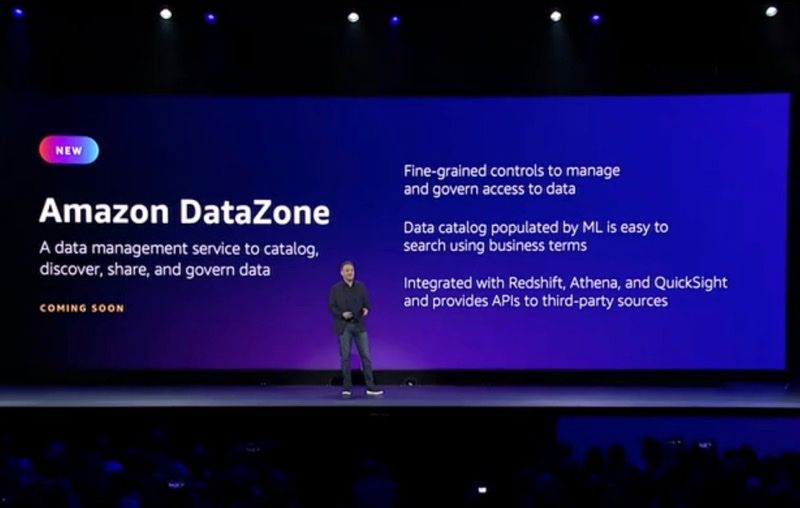

Enter Amazon DataZone, which enables users to discover, catalog, share, and govern data across organisations. What this means in practice is that there is a catalog of available data, with metadata, labels, and descriptions. Authorised consumers of the data can search, browse, and request access, using existing tools: Redshift, Athena, and Quicksight. There is also a partner API for third-party tools; Snowflake and Tableau were mentioned specifically.

The Obligatory AI & ML Segment

I was not the only attendee to note that AWS spent an inordinate amount of time on AI & ML, given AWS' relatively weak position in that market.

Now we're back to talking about Machine Learning®. I'm growing relatively annoyed at the constant overhyping of this market segment in which @awscloud is notably behind its competition, and am starting to take the gloves off as a result.

— Corey Quinn (@QuinnyPig) November 29, 2022

Adam Selipsky talked up the "most complete set of machine learning and AI services", as well as claiming that Sagemaker is the most popular IDE for ML. A somewhat-interesting example is ML-powered forecasting: take a metric on a dashboard and extend it into the future, using ML to include seasonal fluctuations and so on. Of course this is only slightly more realistic than just using a ruler to extend the line, but at least it saves the time needed to make the line look credibly irregular.

More Metaphors

Then we got another beautiful video segment, which Adam Selipsky used to bridge somehow from underwater exploration to secure global infrastructure and GuardDuty. The main interesting announcement in this segment was Amazon SecurityLake, a "dedicated data lake to combine security data at petabyte scale". Data in the lake can be queried with Athena, OpenSearch, and Sagemaker, as well as third-party tools.

It didn’t sound like there was massive commitment to this offering, so the whole segment ended up sounding opportunistic. The whole thing reminded me of Tim Bray's recent tale of how AWS never did get into blockchain stuff: as long as people are going to do something, you might as well make it easy.

In this case, what people are doing is dumping all their logs into one place in the hope that they can find the right algorithm to sift them with and find interesting patterns that map to security issues. The most interesting aspect of SecurityLake is that it is the first tool to support the new Open Cybersecurity Schema Framework format. This is a nominally open format (Cisco and Splunk were mentioned as contributors), but it is notable that the examples in the OCSF white paper are all drawn from AWS services. OCSF is a new format, only launched in August 2022, so ultimate adoption by the industry is still unclear.

Trekking Towards The End

By this point in the presentation I was definitely flagging, but there was another metaphor to torture, this time about polar exploration. Adam Selipsky contrasted the Scott and Amundsen expeditions, which seemed in remarkably poor taste, what with all the ponies and people dying — although the anecdote about Amundsen bringing a tin-smith to make sure his cans of fuel stayed sealed was admittedly a good one, and the only non-morbid part of the whole segment. Anyway, all of this starvation and death — of the explorers, I mean, not the keynote audience, although if I had gone before breakfast I would have been regretting it by this point — was in service of making the point that specific tools are better than general ones.

We got a tour of what felt like a large proportion of AWS' 600+ instance types, with shade thrown at would-be Graviton competitors that have not yet appeared, more ML references with Inferentia chips, and various stories about HPC. Here it was noticeable that the customer example use case uses Intel Xeon chips, despite all of those earlier Graviton references.

One More Metaphor

OH MY GOD. @aselipsky just spent (no joke) 5-7 minutes talking about the power of imagination. Animated well produced video on it. It's clearly building to something huge, what is it what is it what is it...

— Corey Quinn (@QuinnyPig) November 29, 2022

It's talking about Amazon Connect, the @awscloud contact center thing.

There was one more very pretty video on imagination, but it was completely wasted on supply chains and call centres.

There was one last interesting offering, though, building on that earlier point about governance and access. This was AWS Clean Rooms, a solution to enable secure collaboration on datasets without sharing access to the underlying data itself. This is useful when working across organisational boundaries, because instead of copying data (which means losing control over the copy), it reads data in place, and thereby maintains restrictions on that data. Quicksight, Sagemaker, and Redshift all integrate with this service at launch.

There was one issue hanging over this whole segment, though. The Clean Rooms example was from advertising, which leads to a potential (perception of) conflict of interest with Amazon's own burgeoning advertising business. Like another new service, AWS Supply Chain, it's easy to imagine this offering being a non-starter simply because of the competitive aspect, much like retailers prefer to work with other cloud providers than AWS.

Turn It To Eleven

All in all, nothing earth-shattering — certainly nothing like Andy Jassy's cavalcade of product announcements, upending client and vendor roadmaps every minute or so. Maybe that is as it should be, though, for an event which is in its eleventh year. And this may well be why Adam Selipsky opted for a different approach to "the cloud is still in its infancy", when it is so clearly a market that is maturing fast. In particular, we are seeing a maturation in the treatment of data, from a purely technical focus on specific tasks to a more holistic lifecycle view. This shift is very much in line with the expectations of the market; however, at least based on this keynote, AWS is playing catch-up rather than defining the field of competition. In particular, all of the governance tools only work with analytical (OLAP) tools, not with real-time transactional (OLTP) tools. That would be a truly transformative move, especially if it can be accomplished without too much of a performance penalty.

The other thing that is maturing is AWS' own approach, moving inexorably up the stack from simple technical building blocks to full-on turnkey business applications. This shift does imply a change in target buyers, though; AWS' old IT audience may have been happy to swipe a credit card, read the docs, and start building, but the new audience they are quoting with Supply Chain and Clean Rooms certainly will not. It will be interesting to watch this transformation take place.