Why is security so hard?

Since I no longer work in security, I don’t have to worry about looking like an ambulance-chasing sales person, and I can opine freely about the state of the world.

The main problem with security is the intersection of complexity and openness. In the early days of computers there was a philosophical debate about the appropriate level of security to include in system design. The apex of openness was probably MIT’s Incompatible Time-Sharing System, which did not even oblige users to log on - although it was considered polite to do so.

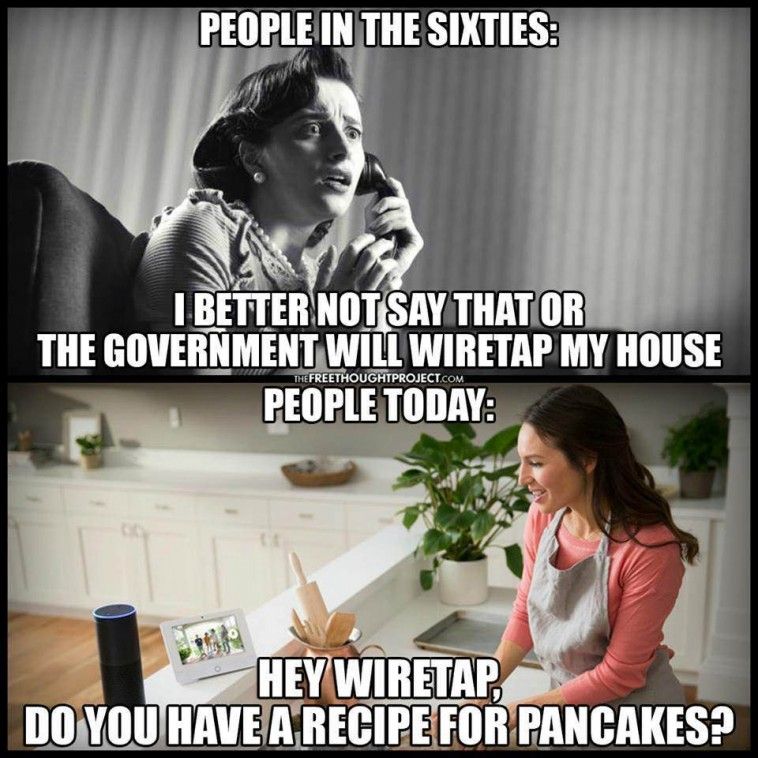

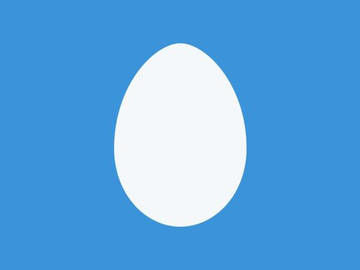

I will just pause here to imagine that ethos of openness in the context of today’s social media, where the situation is so bad that Twitter felt obliged to change its default user icon because the "egg" had become synonymous with bad behaviour online.

By definition, security and openness are always in opposition. Gene "Spaf" Spafford, who knows a thing or two about security, famously opined that:

The only truly secure system is one that is powered off, cast in a block of concrete and sealed in a lead-lined room with armed guards - and even then I have my doubts.

Obviously, such a highly-secure system is not very usable, so people come up with various compromises based on their personal trade-off between security and usability. The problem is that this attempt to mediate between two opposite impulses adds complexity to the system, which brings its own security vulnerabilities.

Ultimately, IT security is a constant Red Queen’s Race, with operators of IT systems rushing to patch the latest flaws, knowing all the while that more flaws are lurking behind those, or being introduced with new functionality.

Every so often, maintainers of a system will just throw up their hands, declare a system officially unmaintainable, and move to something else. This process is called "End of Life", and is supposed to coincide with users also moving to the new supported platform.

Unfortunately this mass upgrade does not always take place. Many will cite compatibility as a justification, and certainly any IT technician worth their salt knows better than to mess with a running system without a good reason. More often, though, the reason is cost. In a spreadsheet used to calculate the return on different proposed investments, "security" falls under the heading of "risk avoidance"; a nebulous event in the future, that may become less probable if the investment is made.

For those who have not dealt with many finance people, as a rule, they hate this sort of thing. Unless you have good figures for both the probability of the future event and its impact, they are going to be very unhappy with any proposed investment on that basis.

The result is that old software sticks around long after it should have been retired.

As recently as November 2015, it emerged that Paris’ Orly airport was still operating on Windows 3.1 - an operating system that has not been supported since 2001.

The US military still uses 8" floppy disks for its ICBMs:

"This system remains in use because, in short, it still works," Pentagon spokeswoman Lt Col Valerie Henderson told the AFP news agency.

And of course we are still dealing with the fallout from the recent WannaCry ransomware worm, targeting Windows XP - an operating system that has not been supported since 2014. Despite that, it is still the fourth most popular version of Windows (behind Windows 7, Windows 10, and Windows 8.1), with 5.26% share.

Get to the Point!

It’s easy to mock people still using Windows XP, and to say that they got no more than they deserved - but look at that quote from the Pentagon again:

"This system remains in use because, in short, it still works"

Windows XP still works fine for its users. It is still fit for purpose. The IT industry has failed to give those people a meaningful reason to upgrade - and so many don’t, or wait until they buy new hardware and accept whatever comes with the new machine.

Those upgrades do not come nearly as frequently as they used to, though. In the late Nineties and early Oughts, I upgraded my PC every eighteen months or so (as funds permitted), because every upgrade brought huge, meaningful differences. Windows 95 really was a big step up from Windows 3.1. On the Mac side, System 7 really was much better than System 6. Moving from a 486 to a Pentium, or from 68k to PowerPC, was a massive leap. Adding a 3dfx card to your system made an enormous difference.

Vice-versa, a three-year-old computer was an unusable pile of junk. Nerds like me installed Linux on them and ran them side by side with our main computers, but most people had no interest in doing such things.

These days, that’s no longer the case. For everyday web browsing, light email, and word processing, a decade-old computer might well still cut it.

That’s not even to mention institutional use of XP; Britain’s NHS, for instance, was hit quite hard by WannaCry due to their use of Windows XP. For large organisations like the NHS, the direct financial cost of upgrading to a newer version of Windows is a relatively small portion of the overall cost of performing the upgrades, ensuring compatibility of all the required software, and retraining literally hundreds of thousands of staff.

So, users have weak incentives to upgrade to new, presumably more secure, versions of software; got it. Should vendors then be obliged to ship them security patches in perpetuity?

Zeynep Tufekci has argued as much in a piece for the New York Times:

First, companies like Microsoft should discard the idea that they can abandon people using older software. The money they made from these customers hasn’t expired; neither has their responsibility to fix defects.

Unfortunately, it’s not that simple, as Steven Bellovin explains:

There are two costs, a development cost $d and an annual support cost $s for n years after the "warranty" period. Obviously, the company pays $d and recoups it by charging for the product. Who should pay $n·s?

The trouble is that n can be large; the support costs could thus be unbounded.

Can we bound n? Two things are very clear. First, in complex software no one will ever find the last bug. As Fred Brooks noted many years ago, in a complex program patches introduce their own, new bugs. Second, achieving a significant improvement in a product's security generally requires a new architecture and a lot of changed code. It's not a patch, it's a new release. In other words, the most secure current version of Windows XP is better known as Windows 10. You cannot patch your way to security.

Incentives matter, on the vendor side as well as on the user side. Microsoft is not incentivised to do further work on Windows XP, because it has already gathered all the revenue it is ever going to get from that product. From a narrowly financial perspective, Microsoft would prefer that everyone purchase a new license for Windows 10, either standalone or bundled with the purchase of new hardware, and migrate to that platform.

Note that, as Steven Bellovin points out above, this is not just price-gouging; there are legitimate technical reasons to want users to move to the latest version of your product. However, financial incentives do matter, a lot.

This is why if you care about security, you should prefer services that come with a subscription.

If you’re not Paying, you’re the Product

Subscription licensing means that users pay a recurring fee, and in return, vendors provide regular updates, including both new features and fixes such as security patches.

As usual, Ben Thompson has a good primer on the difference between one-off and subscription pricing. His point is that subscriptions are better for both users and vendors because they align incentives correctly.

From a vendor’s perspective, one-off purchases give a hit of revenue up front, but do not really incentivise long-term engagement. It is true that in the professional and enterprise software world, there is also an ongoing maintenance charge, typically on the order of 18-20% per year. However, that is generally accounted for differently from sales revenue, and so does not drive behaviour to nearly the same extent. In this model, individual sales people have to behave like sharks, always in motion, always looking for new customers. Support for existing customers is a much lower priority.

Vice versa, with a subscription there is a strong incentive for vendors to persuade customers to renew their subscription - including by continuing to provide new features and patches. Subscription renewal rates are scrutinised carefully by management (and investors), as any failure to renew may well be symptomatic of problems.

Users are also incentivised to take advantage of the new features, since they have already paid for them. When upgrades are freely available, they are far more likely to be adopted - compare the adoption rate for new MacOS or iOS versions to the rate for Windows (where upgrades cost money) or Android (where upgrades might not be available, short of purchasing new hardware).

This is why Gartner expects that by 2020, more than 80 percent of software vendors will change their business model from traditional license and maintenance to subscription.

At Work - and at Home, Too

One final point: this is not just an abstract discussion for multi-million-euro enterprise license agreements. The exact same incentives apply at home.

A few years ago, I bought a cordless phone that also communicated with Skype. From the phone handset, I could make or answer either a POTS call, or a Skype voice call. This was great - for a while. Unfortunately the hardware vendor never upgraded the phone’s drivers for a new operating system version, which I had upgraded to for various reasons, including improved security.

For a while I soldiered on, using various hacks to keep my Skype phone working, but when the rechargeable batteries died, I threw the whole thing in the recycling bin and got a new, simpler cordless phone that did not depend on complicated software support.

A cordless phone is simple and inexpensive to replace. Imagine that had been my entire Home of the Future IoT setup, with doorbells, locks, alarms, thermostats, fridges, ovens, and who knows what else. "Sorry, your home is no longer supported."

With a subscription, there is a reasonable expectation that vendors will continue to provide support for the reasonable lifetime of their products (and if they don’t, there is a contract with the force of law behind it).

Whether it’s for your home or your business, if you rely on it, make sure that you pay for a subscription, so that you can be assured of support from the vendor.