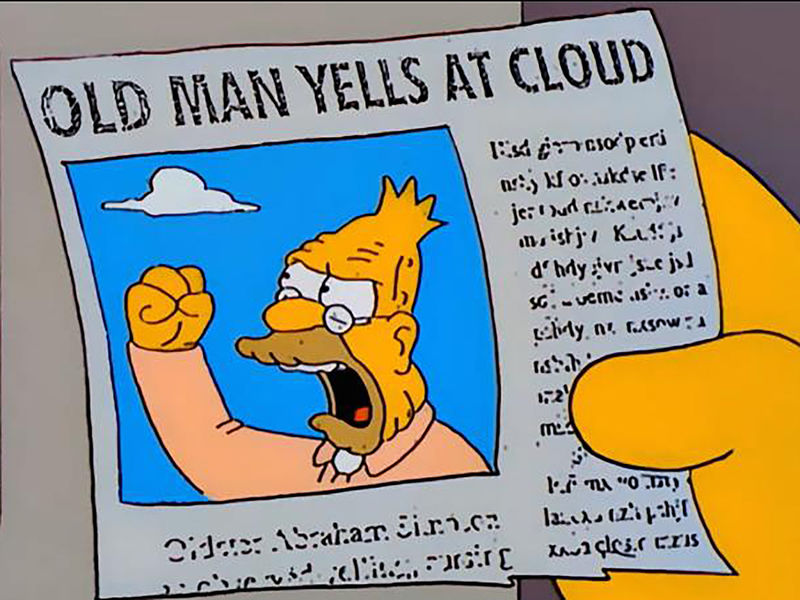

Young people these days, am I right?

We have fallen upon evil times,

And the world has waxed very old and wicked.

Politics are very corrupt.

Children are no longer respectful to their parents.

Author: Naram Sin, King of Chaldea. Date: 3800 B.C.1

I don’t know how long is too long to be in sales, but I have now been doing it for long enough that I can look down at young whippersnappers and their naivety.

Today’s example is actually a perfect storm of sorts, involving Silicon Valley VCs, a Bitcoin startup, and large enterprise processes. I was listening to the a16z podcast, which as usual is about equally irritating and enlightening. The guest on this particular episode was one Adam Ludwin, whose claim to fame is as the founder of a Bitcoin - sorry, blockchain startup, called Chain.

I find the techno-utopianism of everything associated with Bitcoin to be jarring at the best of times, but Ludwin and Chain have an interesting angle on it. Instead of enabling drug dealers and software extortionists, they are trying to enable large financial institutions to carry out their business using the blockchain, instead of the weird semi-analogue hodgepodge of processes that banks run on today.

I’m not going to get too deeply into what Chain are up to - if you want to find out about that, you can go listen to the episode. What I found jarring was his surprise at what he found when selling into those large financial institutions. Anyone who has spent time selling into large enterprises could have told him this, but apparently he had to learn it the hard way.

For the benefit of everyone else, here are a couple of key points.

Executive Sponsorship

Nothing gets done without buy-in from the CEO. (direct link to relevant quote in podcast)

NO REALLY STOP THE PRESSES HOLD THE FRONT PAGE

Let’s get real: moving anything that is currently working to unproven technology such as the blockchain is going to require strong executive sponsorship. This is not unique to the financial industry, either. Whenever there is an existing process in place that works, however creakily, there is resistance to any proposed solution.

There is nothing inherently wrong with this resistance: the existing process has been refined over time and is well understood, including its failure modes. The proposed new solution, however, is by definition unproven, and will almost certainly require a period of acclimatisation before it becomes as reliable as what went before, let along delivering additional value.

Graphic stolen from Ben Evans

The people who are least likely to see the problem with the way things have always been done are the people who are in charge of that existing process. They are trapped on a local maximum, and while they may accept the theoretical existence of higher maxima elsewhere, to reach them they would have to cross a valley of lower service, lower user satisfaction, possibly lower bonuses, and even perhaps place their jobs at risk.

This is why the most fearsome competitor that you face when pitching anything transformative is not That Other Company, but the Do-Nothing Corporation. You need a very good answer to the question "why do anything?" before you can even get to "why do this?", "why now?", and eventually, "why do it with this company?".

People in upper management, on the other hand, are there specifically to take a strategic view, accepting tactical defeats in the name of the ultimate strategic victory. If you want to change anything that is required for a company to operate, you will need strong executive sponsorship: someone who not only knows the current state, but understands why it cannot continue, and is willing to engage with you to investigate alternatives.

What is tricky for many people just getting into enterprise sales is that the initial pattern often looks the same with and without sponsorship: an evaluation, a proof of concept, a pilot project, or an engagement with the innovation lab. There will be meetings with architects, CTOs, requests for this and that, strategy sessions, deep dives, and workshops.

The key point, though, is that precisely none of this frenzied activity will actually lead to a deal and a production implementation without that executive sponsorship. Green sales people can waste a lot of time and resources going through these motions and not achieve any results because they missed that all-important first step.

On the other hand, once you have a sponsor who can make things happen for you, the evaluation will go that much more smoothly. Partly this is because you can call on your executive sponsor to sort out the inevitable brown M&Ms sorts of problems, but mostly it is because they will clarify what is an actual business requirement versus technical curiosity or "nice to have" feature.

So far so good, right? Well, if it were that simple, everyone would be doing it. The other issue is that it can be difficult to find anyone that has visibility into the whole process - which is the other point I want to discuss.

Distributed Knowledge

"At any given institution, it’s very very rare to find someone who actually knows how the whole thing works." (direct link to relevant quote in podcast)

This is something else that people don’t always get when they begin dealing with large organisations. Very few people have visibility into the whole problem2. Here is an example from my own past:

Years ago, I was the tech guy on a team selling to a mobile telco. As part of our business case, we were trying to quantify the impact of downtime on a system that activated SIM cards. We had some numbers from IT, but they were incomplete. We rounded them out with some numbers from the helpdesk, but we kept feeling we were missing something. Finally, the sales guy stopped off at a couple of corner shops that sold the SIM cards, and found that the impact was far greater than anyone imagined. It turned out that the shops rarely activated the SIM cards with the customer in the shop, but did them all in a batch at closing time. This created the overload spikes which were taking the central system down, but it also meant that the downtime was costing far more than anyone imagined.

In that situation, when we asked the IT team, they described the part of the problem that they saw. Actually, it was more complex than that; we had to speak to a number of dedicated teams within IT, from servers, to databases, to middleware, to networks - but at least we were able to find people within IT who did have visibility across the IT parts of the problem. The main point, though, is that as far as IT was concerned, everything was fine. The parts that they saw were doing fine, all of their indicators were in the green except for a couple, and they believed themselves to be on track to address those.

Support had an idea that something was wrong, but it was only at certain times, and at other times everything was fine, so the problem seemed to be contained.

Meanwhile, in the corner shops, customers were getting frustrated and picking up the competitors’ SIM cards instead, because they could actually activate those and use them to make phone calls.

It turned out that literally nobody within the company understood the entire end-to-end process. This was a core business process: we were dealing with a mobile telco, and the process we were analysing was the activation of new subscriber SIM cards. One of the key metrics that the company measured itself against was churn, the difference between customers acquired versus those lost to their competition - so customer acquisition was a critical step, and yet nobody truly understood the entire process of how new customers were acquired.

What I learned is that this is normal. The sorts of processes that modern business runs on are too complex to be understood in their entirety - not when there are a hundred and one other tasks demanding people’s attention. When selling to these organisations, we need to ensure that we understand what we are proposing that they replace - and this means talking to many different people, because nobody sees the whole picture.

People working inside complex processes are busy with individual trees, and not necessarily focusing on the entire forest. Vice versa, if we are to propose that foresters change how they manage their trees, we had better have a pretty comprehensive picture of why.

Anyway, if you are a brash startup planning to sell into large corporations, just be aware that there is a lot going on inside those buildings - and much of it even makes sense, if you take the time to understand it. Selling to enterprise is different from selling to consumers or SMB, and needs to be approached with different tools.

Image by Jakub Sejkora via Unsplash

-

Yes, I know it’s apocryphal, but it’s still a good quote! ↩

-

Which is also why I tend not to believe any conspiracy theory requiring perfect functioning of a large bureaucracy. Getting the whole mass pointed vaguely in the same direction is so hard that any claim of additional agility or intelligence simply beggars belief. ↩