The Internet is outraged by… well, a whole lot of things, as usual, but in particular by Apple. For once, however, the issue is not phones that are both unexciting and unavailable, lacking innovation and wilfully discarding convention, and also both over- and under-priced. No, this time the issue is apps, and in particular VPN apps.

Authoritarian regimes around the world (Russia, "Saudi" Arabia, China, North Korea, etc) have long sought to control their populations' access to information in general, and to the Internet in particular. Of course anyone with a modicum of technical savvy - or a friend, relative, or passing acquaintance willing to do the simple setup - can keep unfettered access to the Internet by going through a Virtual Private Network, or VPN.

A VPN does what it says on the tin: it creates a virtual network that connects directly with an endpoint somewhere else; importantly, somewhere outside the authoritarian regime's control. As such, VPNs have always existed in something of a grey area, but now China (the People's Republic, not that other China) has gone ahead and formally banned their use.

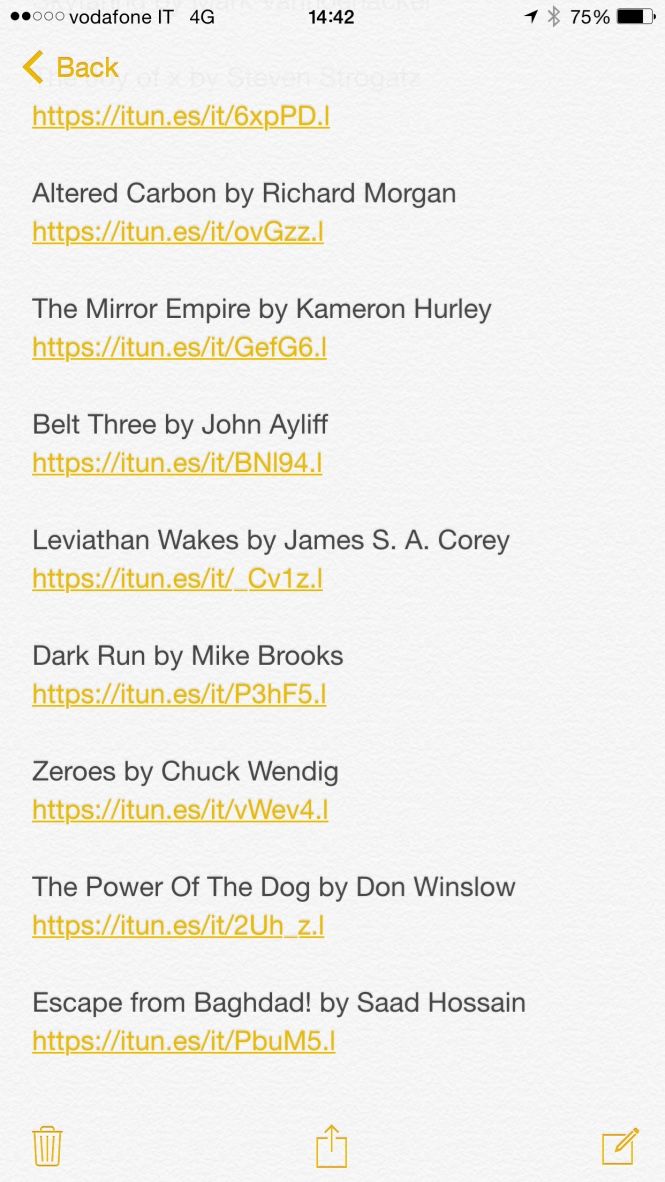

In turn, Apple have responded by removing unregistered VPN apps (which in practical terms means all of them) from their App Store in China. In the face of the Internet's predictable outrage, Apple provided this bald statement (via TechChrunch):

Earlier this year China’s MIIT announced that all developers offering VPNs must obtain a license from the government. We have been required to remove some VPN apps in China that do not meet the new regulations. These apps remain available in all other markets where they do business.

Now Apple do have a point; the law is indeed the law, and because they operate in China, they need to enforce it, just as they would with laws in any other country.

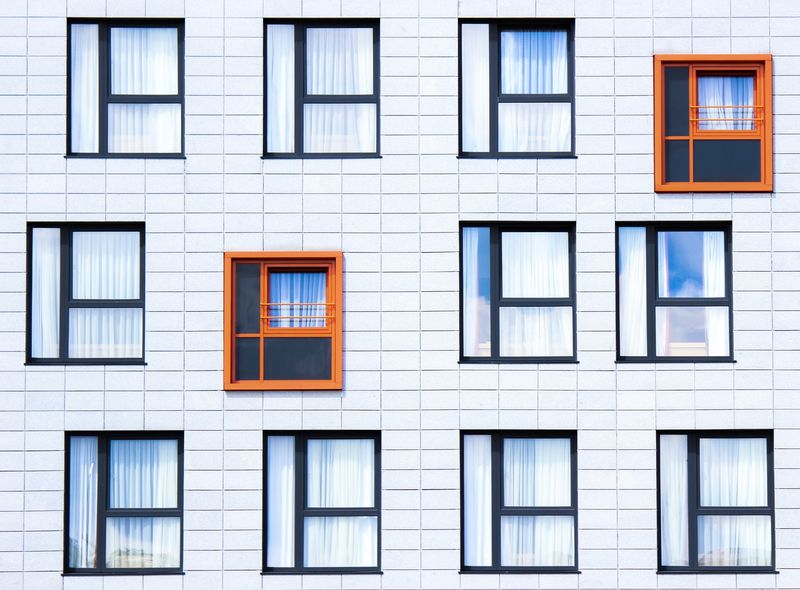

Here's the rub, though. By the regionalised way they have set up their App Store service, they have made themselves unnecessarily vulnerable to this sort of arm-twisting by unfriendly governments. Last time I wrote about geo-fencing and its consequences, the cause of the day was Russia demanding removal of the LinkedIn app, and China (them again!) demanding removal of the New York Times app. As I wrote at the time, companies like Apple originally set up the infrastructure for these geographic restrictions to enable IP protection, but the same tools are being repurposed for censorship:

This sort of restriction used to be "just" hostile to consumers. Now, it is turning into a weapon that authoritarian regimes can wield against Apple, Google, and whoever else. Nobody would allow Russia to ban LinkedIn around the world, or China to remove the New York Times app everywhere - but because dedicated App Stores exist for .ru and .cn, they are able to demand these bans as local exceptions, and even defend them as respecting local laws and sensibilities. If there were one worldwide App Store, this gambit would not work.

The argument against the infrastructure of laws and regulations that was put in place to enable (ineffective) IP restrictions was always that it could be, and would be, repurposed to enable repression by authoritarian regimes. People scoffed at these privacy concerns, saying "if you have nothing to hide, you have nothing to fear". But what if your government is the next to decide that reading the NYT or having a LinkedIn profile is against the law? How scared should you be then?

If you are designing a social network or other system with the expectation of widespread adoption, these days this has to be part of your threat model. Otherwise, one day the government may come knocking, demanding your user database for any reason or no reason at all - and what seemed like a good idea at the time will end up messing up a lot of people's lives.

Product designers by and large do not think of such things, as we saw when Amazon decided that it would be perfectly reasonable to give everyone in your address book access to your Alexa device - and make it so users could not turn off this feature without a telephone call to Amazon support.

How well do you think that would go down if you were a dissident, or just in the social circle of one?

Our instinctive attitude to data is to hoard them, but this instinct is obsolete, forged in a time when data were hard to gather, store, and access. It took something on the scale of the Stasi to build and maintain profiles on even six million citizens (out of a population of sixteen million), and the effort and expense was part of what broke the East German regime in the end. These days, it's trivial to build and access such a profile for pretty much anyone, so we need to change our thinking about data - how we gather them, and how we treat them once we have them.

Personal data are more akin to toxic waste, generated as a byproduct of valuable activity and needing to be stored with extreme care because of the dire consequences of any leaks. Luckily, data are different from toxic waste in one key respect: they can be deleted, or better, never gathered in the first place. The same goes for many other choices, such as restricting users to one particular geographical App Store, or making it easy to share your entire contact list (including by mistake), but very difficult to take that decision back.

What other design decisions are being made today based on obsolete assumptions that will come back to bite users in the future?

UPDATE: And there we go, now Russia is following China’s example and banning VPNs as well. The idea of a technical fix to social and legal problems is always a short-term illusion.

Image by Sean DuBois via Unsplash