Once again, the seemingly unkillable idea of modular phones rears its misshapen head.

The first offender is VentureBeat, with a breathless piece entitled The dream of Ara: Inside the rise and fall of the world’s most revolutionary phone.

record scratch

Let me stop you right there, VentureBeat. Ara is not a "revolutionary phone" at all, let alone "the world's most revolutionary phone", for the very good and sufficient reason that Project Ara never got around to shipping an actual phone before it was ignominiously shut down.

"Most ambitious phone design", maybe. I’d also settle for "most misguided", but that would be a different article. Whatever Ara was, it was not "revolutionary", because otherwise we would all be using modular phones. Even the most watered-down version of that idea, LG’s expandable G5 phone design, is now dead - although in their defence, at least LG did actually ship a product somewhat successfully.

Now Andy Rubin, creator of Android, is back in the news, with plans for a new phone… which sounds like it may well be modular:

It's expected to include […] the ability to gain new hardware features over time

This is a bold bet, and Andy Rubin certainly knows more about the mobile phone market than I do - but here’s why I don’t think a modular phone is the way to go.

Take a Step Back - No, Further Back

The reason I was sceptical about Project Ara’s chances from the beginning goes back to Clayton Christensen’s Disruption Theory. I have written about disruption theory before, so I won’t go into too much length about it here, but basically disruption states that in a fast-developing market, integrated products win because they can take advantage of rapid advances in the field. Vice versa, in a mature market products win by modularising, providing specific features with specific benefits or at a lower cost than the integrated solutions can deliver.

Disruption happens when innovation slows down because further innovation requires more resources than consumers are willing to invest. In this scenario, incumbent vendors continue to chase diminishing returns at the top of the market, only to find themselves undercut by modular competitors delivering "good enough" products. Over time, the modular products eat up the bulk of the market, leaving the ex-incumbents high and dry.

If you assume that the mobile phone market is mature and all development is just mopping up at the edges, then maybe a modular strategy makes sense, allowing consumers to start with a "good enough" basic phone and pick and choose the features most important to them, upgrading individual functionality over time. However, if the mobile phone market is still advancing rapidly and consumers still see the benefit from each round of improvements, then fundamental upgrades will happen frequently enough that integrated solutions will still have the advantage.

Some of the tech press seem to be convinced that we have reached the End of History in mobile technology. Last year’s iPhone 7 launch was the epitome of this view, with the consensus being that because the outside of the phone had not changed significantly compared to the previous generation, there was therefore no significant change to talk about.

The actual benchmarks tell a different story. The iPhone 7 is not only nearly a third faster than the previous generation of iPhone across the board, it also compares favourably to a 2013 MacBook Pro.

That type of year-over-year improvement is not the mark of a market that is ripe for modular disruption.

What Do Users Say?

The other question, beyond technical suitability, is whether users would consider a product like Project Ara, or LG’s expandable architecture. The answer, at least according to LG’s experience, is a resounding NO:

An LG spokesperson commented that consumers aren’t interested in modular phones. The company instead is planning to focus on functionality and design aspects

Consumers do not see significant benefits from the increase in complication that modularisation brings, preferring instead to upgrade the entire handset every couple of years, at which point every single component will be substantially better.

And that is why the mobile phone market is not ready for a modular product, instead preferring integrated ones. If every component in the phone needs to be upgraded anyway, modularisation brings no benefit; it’s an overhead at best, and a liability at worst, if modules can become unseated and get lost or cause software instability.

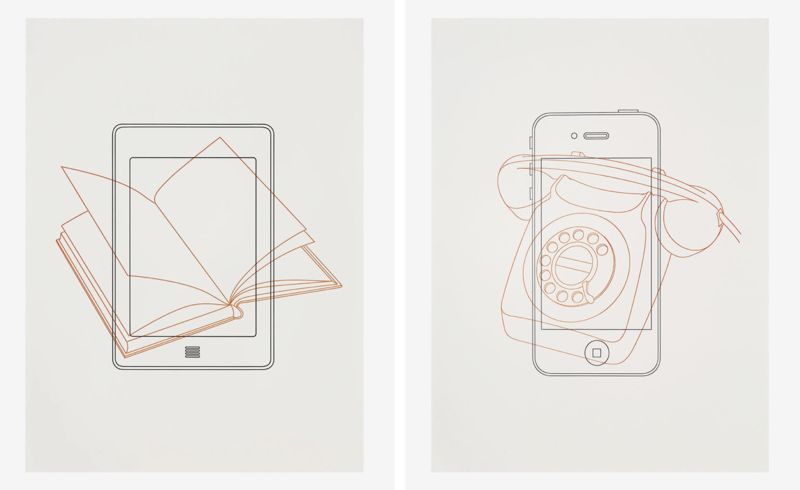

At some point the mobile phone market will probably be disrupted - but I doubt it will be done through a modularised hardware solution in the vein of Project Ara. Instead, I would expect modularisation to take place with more and more functionality being handed off to a cloud-based back-end. In this model, the handset will lose many of its independent capabilities, and revert to being what the telephone has been for most of its history: a dumb terminal connected to a smart network.

But we’re not there yet.

Images by Pavan Trikutam and Ian Robinson via Unsplash