Good Morning!

Having used one of those electric scooters, I am now an expert on micromobility, and I have opinions.

Last week I was in Paris on business, which is always fun. This was a proper multimodal trip, encompassing the following forms of transportation:

The moto taxi is always a somewhat terrifying experience, but I’ve been using them for years. It’s basically the only way to get anywhere in Paris at rush hour in less than an hour. If you haven’t had the pleasure, the idea is that you ride on the back of a Honda Goldwing (or sometimes one of those large scooters), which is big enough for there to be plenty of space for a pillion passenger and for carry-on luggage. The rider kits you out with a reinforced jacket, a helmet (with disposable liner), and a waistcoat with airbags that is connected to the bike via a breakaway connection. If you are unlucky enough to come off the bike, airbags around the neck will inflate and (with any luck) prevent the worst-case scenario.

Perched up high on the back of a Goldwing is the best vantage point from which to appreciate that most of the gridlock is composed of cars with only a single occupant. This is obviously not ideal for anybody, which is why alternative forms of transportation are such a hot topic lately.

Later that day, all done with my meetings, I was going to take a Metro to my hotel – but there was some sort of delay on the line, and then I spotted a scooter just standing there… I already had the Lime app from using it in Berlin with the dockless electric-assist bicycles there, so why not?

Unfortunately that first scooter had a cut brake line – the Bay Area does not have a monopoly on scooter saboteurs! By this point I was committed, though, and the app showed me that there was another scooter just around the corner with a full charge.

This second scooter was undamaged and zipped along quite happily. In the centre of Paris 25 km/h is plenty fast enough to keep up with traffic, and most larger streets have bike lanes which are physically separated from the car traffic, so it’s a very fun experience. I was only travelling for a single overnight, so my rucksack was no problem.

If I had had my car with me, I would first of all have had to pay through the nose for parking1, not to mention the environmental impact of start-stop driving (this is what is driving the plan to ban internal-combustion vehicles in Paris by 2030). On top of that, driving in a congested situation like the centre of Paris is actually no fun at all.

The problem with the car is that my mobility needs would have been over-served, so I would only have experienced the downsides. The calculus would admittedly have changed slightly if it had been raining, or if I had had more luggage than a single rucksack, but then the delay on the Metro might have seemed more acceptable.

Either way, a full-size car is overkill in most (European) cities. Already today, my car hardly ever turns a wheel for journeys of less than a dozen kilometres. I would not want to ride a scooter to the airport (at 25 km/h!), but for a quick trip around town, a scooter or a bicycle are very hard to beat – especially if they could easily be augmented with public transport.

One factor that will help with uptake of these alternative forms of transportation is an easier way to bundle different forms of transportation together into a single logical "trip". This sort of aggregation is already beginning to emerge in various places: in San Francisco, the Uber app will let you rent JUMP bikes, while in Milan, dockless electric scooters can be unlocked using the Telepass app, which also lets users pay for motorway tolls, parking, congestion charges, and so on.

My SF friends object to the scooters because they get left all over the place, obstructing pavements both when they are parked and when idiots ride the scooters on those pavements ("sidewalks", whatever) instead of sticking to the road or bike path. This is absolutely a real problem, but it’s not intrinsic to the scooters. It’s a combination of user education and available infrastructure. The Lime app I used in Paris asked me to take a photograph when I parked the scooter to make sure that it was parked somewhere appropriate. There are also red boxes on the map where the scooters cannot be left for any reason; Lime will charge users for retrieval if scooters are left in these areas.

These app features will already help to ensure that the scooters are in nobody’s way at rest. In motion, Paris’ excellent network of bike lanes reduces the incentive to ride on pavements. Given the width of American streets, there is plenty of room to add bike lanes there too, and to include physical protections beyond just a coat of paint. If there’s room to do this in the centre of Paris, there is room in every single American city, no exceptions.

I thoroughly enjoyed my multimodal trip, and I look forward to many more in the future.

Seriously, last time I parked a car in central Paris, it cost more to house the car than the hotel room to house its human occupants. Supply/demand, and so on, it does make sense, but it stung quite a bit at the time! ↩

Even though I no longer work directly in marketing, I’m still adjacent, and so I try to keep up to date with what is going on in the industry. One of the most common-sensical and readable voices is Bob Hoffman, perhaps better known as the Ad Contrarian. His latest post is entitled The Simple-Minded Guide To Marketing Communication, and it helpfully dissects the difference between brand advertising and direct-response advertising (emphasis mine):

[…] our industry's current obsession with precision targeted, one-to-one advertising is misguided. Precision targeting may be valuable for direct response. But history shows us that direct response strategies have a very low likelihood of producing major consumer facing brands. Building a big brand requires widespread attention. Precision targeted, one-to-one communication has a low likelihood of delivering widespread attention.

Now Bob is not just an armchair critic; he has quite the cursus honorum in the advertising industry, and so he speaks from experience.

In fact, events earlier this week bore out his central thesis. With the advent of GDPR, many US-based websites opted to cut off EMEA readers rather than attempt to comply with the law. This action helpfully made it clear who was doing shady things with their users’ data, thereby providing a valuable service to US readers, while rarely inconveniencing European readers very much.

The New York Times, with its strong international readership, was not willing to cut off overseas ad revenue. Instead, they went down a different route (emphasis still mine):

The publisher blocked all open-exchange ad buying on its European pages, followed swiftly by behavioral targeting. Instead, NYT International focused on contextual and geographical targeting for programmatic guaranteed and private marketplace deals and has not seen ad revenues drop as a result, according to Jean-Christophe Demarta, svp for global advertising at New York Times International.

Digiday has more details, but that quote has the salient facts: turning off invasive tracking – and the targeted advertising which relies on it – had no negative results whatsoever.

This is of course because knowing someone is reading the NYT, and perhaps which section, is quite enough information to know whether they are an attractive target for a brand to advertise to. Nobody has ever deliberately clicked from serious geopolitical analysis to online impulse shopping. However, the awareness of a brand and its association with Serious Reporting will linger in readers’ minds for a long time.

The NYT sells its own ads, which is not really scalable for most outlets, but I hope other people are paying attention. Maybe there is room in the market for an advertising offering that does not force users to deal with cookies and surveillance and interstitial screens and page clutter and general creepiness and annoyance, while still delivering the goods for its clients?

🖼️ Photo by Kate Trysh on Unsplash

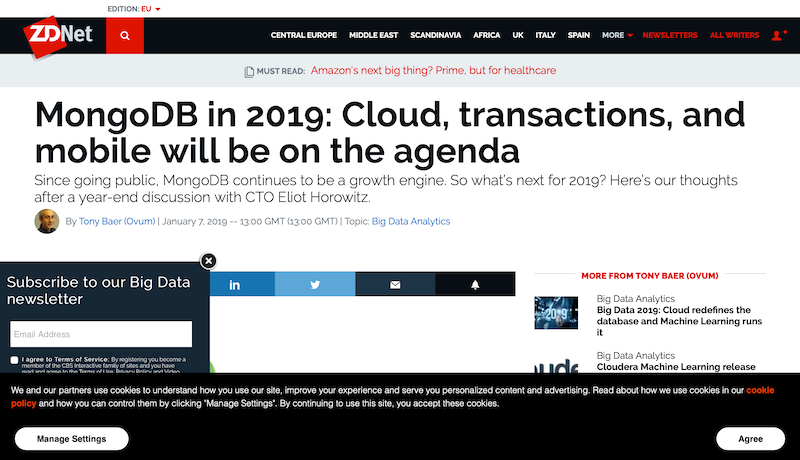

Why I love Reader mode in Safari – a tale in two screenshots.

I have to scroll down more than an entire screen to see even the first line of the text. This design is actively user-hostile.

Much better! I still have the title and the sub-heading, but I can see the image and the first paragraph of the text. Result.

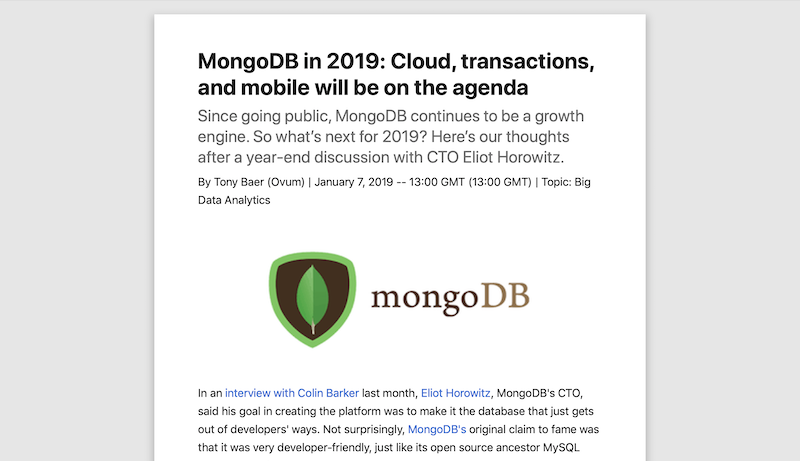

What is even better is configuring Safari to use Reader mode automatically on offending websites:

Just a pity I can’t do that on iOS; the setting is only available in the macOS version of Safari. Still, a guy can dream…

UPDATE: I was wrong! It is in fact possible to do the same thing on iOS; just hold down on the Reader Mode icon.

Not especially discoverable, perhaps, but very useful. In fact, since I found out about this, it turns out that the same thing works on desktop Safari.

They said they need real-world examples, but I don’t want to be their real-world mistake

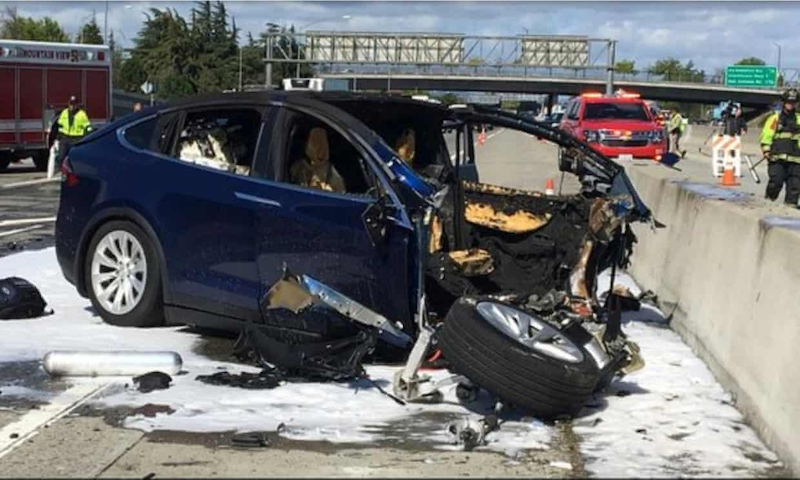

That quote comes from a NYT story about people attacking self-driving vehicles. I wrote about these sentiments before, after the incident which spurred these attacks:

It’s said that you shouldn’t buy any 1.0 product unless you are willing to tolerate significant imperfections. Would you ride in a car operated by software with significant imperfections?

Would you cross the street in front of one?

And shouldn’t you have the choice to make that call?

Cars are just the biggest manifestation of this experimentation that is visible in the real world. How often do we have to read about Facebook manipulating the content of users’ feeds – just to see what happens?

And what about this horrific case?

Uhoh, This content has sprouted legs and trotted off.

Meanwhile, my details were included in last year’s big Marriott hack, and now I find out that my passport details may have been included in the leaked information. Marriott’s helpful suggestion? A year’s free service – from Experian. Yes, that Experian, the one you know from one of the biggest hacks ever.

I don’t want to be any company’s real world mistake in 2019.

🖼️ Photo by chuttersnap on Unsplash

Apple’s terrible, bad, no good updated guidance (not actual results yet, note) was pretty much unavoidable – as were the reams of commentary on the subject. Nevertheless, I had some thoughts of my own to add to the torrent.

Tim Cook cited slowing sales in China as the primary factor in his guidance:

While we anticipated some challenges in key emerging markets, we did not foresee the magnitude of the economic deceleration, particularly in Greater China. In fact, most of our revenue shortfall to our guidance, and over 100 percent of our year-over-year worldwide revenue decline, occurred in Greater China across iPhone, Mac and iPad.

China’s economy began to slow in the second half of 2018. The government-reported GDP growth during the September quarter was the second lowest in the last 25 years.

We believe the economic environment in China has been further impacted by rising trade tensions with the United States.

In other words, a combination of a slowdown in the Chinese domestic economy, and the US sanctions starting to bite. I am sure these are both factors; China is the only market with the size and depth to be able to offer the sorts of growth that Apple investors have become used to. Apple’s stock price has long been a lagging indicator, underpriced (in price/earnings ratio terms) by investors stuck in the late Nineties who still thought of Apple as a company that was perpetually circling the drain.

In contrast the stock is now arguably overpriced, as it is hard to imagine another product ever again offering growth rates comparable to the iPhone in its first decade. The Apple Watch, a perfectly respectable business in its own right and a product that completely dominates its sector, is widely decried as a failure because it cannot match the iPhone’s runaway success. The iPad, a smaller business than the Watch, is nevertheless the tablet, with everyone else an also-ran. However, both of these are rounding errors compared to the iPhone business.

Meanwhile, for a company whose products are famously "Designed by Apple in California", but "Assembled in China", any trade sanctions are sure to cause a number of headaches. The sanctions apply most obviously to finished products, but any extended trade war could also affect the supply of raw materials, IP transfer, or relationships with component vendors.

However, I do not think that the Chinese economy and sanctions represent the whole story here.

As everyone concentrates on the impact of US sanctions and wider macro-economic trends, there is another factor whose unfortunate timing is compounding the bad news for Apple.

As a general rule, people don’t upgrade their phone every year. Even among my tech enthusiasts friends, most are on what is known as a "tick-tock" upgrade path, meaning that they change their phone every other year. One reason for this pattern (apart from the obvious one of budget) is that Apple’s hardware generations are not all equal. Historically, a new form factor is launched one year, and then in the following year it is refined and improved.

These "improvement" years used to be known as the "S" models, as in 3GS, 4S, 5S, and 6S. People who wanted new form factors would buy on the non-S year, while those who craved reliability and performance improvements would buy on the S year. So far so good – until the iPhone 6.

As an example, the iPhone 6 was the first to offer the option of a larger screen, in the form of the iPhone 6 Plus, long after most Android manufacturers had launched their own larger-screen models.1 The pent-up demand for a larger iPhone caused many users to upgrade out of cycle, pulling demand forward that would otherwise have hit during the 6S cycle.

The same thing happened with the iPhone X. As the first iPhone to do away with the home-button, relying instead on Face ID, and offering that gorgeous all-screen view, it again caused many users to upgrade early. I was one of them, trading in my perfectly functional year-old iPhone 7 Plus for an iPhone X instead of waiting another year. If it had not been for the iPhone X, I doubt I would have bothered to upgrade to an iPhone 8, which is not different enough from a 7 to justify the outlay.

In contrast to the visible differences between the iPhone 7 and iPhone X, the iPhone XS and XR offer little to tempt owners of the iPhone X to upgrade early. To compound that effect, the steep price increases of the new models may be actively dissuading users from upgrading, putting them onto a three-year cycle. In other words, we are seeing a trough in demand that is caused at least in part by a previous bulge around the launch of the iPhone X.2 The sheer desirability and newness of that phone may also have obscured the impacts of the price increase – but having made such large investments, users are that much more reluctant to spend even more on newer models.

This effect may be even greater in China, as Ben Thompson has written before:

That, though, is a long-term problem for Apple: what makes the iPhone franchise so valuable — and, I’d add, the fundamental factor that was missed by so many for so long — is that monopoly on iOS. For most of the world it is unimaginable for an iPhone user to upgrade to anything but another iPhone: there is too much of the user experience, too many of the apps, and, in some countries like the U.S., too many contacts on iMessage to even countenance another phone.

None of that lock-in exists in China: Apple may be a de facto monopolist for most of the world, but in China the company is simply another smartphone vendor, and being simply another smartphone vendor is a hazardous place to be. To be clear, it’s not all bad: in China Apple still trades on status and luxury; unlike the rest of the world, though, the company has to earn it with every release, and that’s a bar both difficult to clear in the abstract and, given the last two iPhones, difficult to clear in reality.

John Gruber made the same connection, and commented succinctly:

By Thompson’s logic the iPhone X should have done well in China, because it looked new, and the XS/XR would disappoint in China because they didn’t. And, well, here we are.

I am hardly going to offer advice,3 either to Tim Cook or to Apple investors. Tim Cook sees numbers that nobody outside the company does, and has certainly already put plans in motion whose effects we will only see several quarters from now. An aircraft carrier4 the size of Apple does not turn on the spot. Meanwhile Apple investors, taken as a group, have never displayed any particularly deep understanding of the company’s business, and will no doubt continue to do their own thing.

As an Apple user, however, I am not particularly worried – yet. The moment of truth will come later this year, with the launch of the successor phones to the XS and XR. If these phones are sufficiently compelling – and come at a suitably accessible price point, at least for entry-level options – demand would presumably plateau back out, all macro-economic trends being equal.

If on the other hand Apple launches a successor to the XS that is not immediately and obviously different – as the iPhone 7 was not visibly different from the 6 and 6S – and continues its price increase trend, then there may be an issue with longer-term viability.

Apple will probably never again have another iPhone-type product, with such universal appeal and monstrous growth. Everything from now on is about getting iPhone users to upgrade their device regularly, purchase ancillary products (AirPods, Watch, HomePod, Apple TV), and consume Apple services (Music, plus the long-rumoured video subscription service).5 That is a different kind of business, and expectations should be set accordingly.

I refuse to call them "phablets". 🤮 ↩

Attempts to increase desirability with new colours, as on the iPhone XR, and especially the Product Red models released out of phase with the main launch of their parent models, do not seem to have had a measurable impact – although it’s hard to tell without detailed sales data. ↩

Although I still think that something the size of an iPhone SE, all screen in the iPhone X style, and priced somewhere significantly below the mainstream XS, would be a bigger hit and provide clearer differentiation at the top end of the range than the XR. Or might that be coming in September, when all the iPhone models revert to sharp edges, as we have seen on the new iPad Pro? 🤔 ↩

That’s an AirPower reference! Zing! 😢 ↩

Oh yes, and Mac users – but that platform plateaued a long time ago. I love the macOS as a user, but it’s not a growth market. iPad – still not sure that Apple knows what it wants to do with iPad. ↩

One of the most powerful memes in tech is the Innovator’s Dilemma. Professor Clayton Christensen’s theory posits moves from integrated products to modularised ones, driven by waves of innovation at different levels. The world of tech swings regularly between these poles of integration and modularisation. Sometimes the whole industry moves at once, as in the ongoing move away from modular desktop computers and towards all-in-one laptops, tablets, and hybrids of the two, with modularisation moving to other levels of the stack. At other times competing models are in play at the same time, with little agreement as to which is better.

Apple is often cited as a counter-example, the archetypal integrated company that defies the conventional wisdom of modularisation exemplified by the infinite variety of the Android platform. One counter-counter-example that often comes up is Maps, and I would like to take a moment to explore (sorry – not sorry) this point.

From launch, Apple Maps was derided as not just a failure, but an actively wrong and misguided choice by Apple. It even gets brought up as the ultimate negative example, as in this M G Siegler piece about Instagram data: "The data makes Apple Maps look like a pristine globe of information". Google had mapping and navigational data that were objectively better, the thinking went, so Apple should simply continue to adopt this external module within their own platform, regardless of consequences.

There is a philosophical aspect to this debate, of course, which may have more currency today than it did at the time. As the famous adage goes, if you’re not paying, you’re the product. Certainly with Google Maps, gathering and analysing users’ personal data was very much a key goal of Google’s, both for the altruistic reason of improving mapping and routing data, and for the more irritating one of contributing to the ever more detailed profiles it keeps of all of us in order to pitch us en masse to advertisers.1

Apple had never been entirely comfortable with this situation, and exacted large payments from Google in return for its privileged position within iOS.2 With the launch of iOS 6, Apple deprecated the use of Google’s data as a source for the built-in Maps application.

Note that Google’s own Maps app was never banned from Apple’s iOS or from its accompanying App Store.3 The difference between the systemwide Apple Maps and Google Maps (or any other third-party mapping app, for that matter) was the integration with all other apps that needed mapping data. In much the same way that tapping on a link would open the built-in Safari web browser, tapping on an address would open the built-in Apple Maps app. Using a third-party web browser, mapping app, or chat/IM or email client, required explicit action by the user each and every time.

Some users objected on grounds of principle to the deep integration of first-party apps and the consequent exclusion of third-party ones. Windows desktop operating systems had trained users to install any number of third-party utilities and widgets, either as replacements for system components or to extend native functionality. iOS did not work this way.

Apple had always preferred an integrated approach, producing both its own hardware and its own operating system ever since the original Apple ][, and complementing that with suites of its own applications. In the 90s I had an Apple StyleWriter printer attached to my Macintosh LC, which I interacted with through an Apple monitor, keyboard, and mouse. Displayed on that monitor was a ClarisWorks document, which was of course owned by Apple as well. Sure, it was possible to run Microsoft Office, and even (for a while) Internet Explorer. In fact, in the doldrums of the early 2000s, after the demise of Cyberdog, Apple’s first attempt at a web browser, and before the rise of Safari with OS X, Microsoft’s was the best browser option on the Mac.

This moment of dependence on third parties had its benefits – keeping the company alive at a very difficult time, for instance – but robbed Apple of ultimate control. As owners increasingly expected to be able to personalise the behaviour of their Macs with custom extensions, those systems became increasingly unstable. The introduction of OS X addressed many of those issues by replacing the creaking foundations of classic Mac OS with the Darwin kernel, but still gave users quite a lot of control. When it came time to launch iOS, however, Apple’s pre-existing philosophical bent towards opinionated design combined with the very real limitations of the hardware of the day to produce a "walled garden" where only Apple’s apps would run. The original iPhone did not even have an App Store; instead, Apple envisioned that third-party functionality would be provided through web apps (never mind that EDGE connectivity was not really up to the job, even in 2006).

Apple did eventually relent and allow third-party apps to run on iPhones, but always in a very controlled manner, with strict sandboxing preventing apps from interfering with each other. This separation also prevented apps from interacting with each other at all, to the point that copy&paste functionality only arrived on iOS with 3.0, released in 2009, and was heralded as a major innovation when it did.

Even then, Apple maintained strict control over core functionality, giving users no ability to replace the standard web browser, email client, to-do list, and more. The Maps app was also part of this list, but used third-party data from Google for its functionality. Tensions had been brewing over this arrangement for a couple of years already, with Google introducing turn-by-turn navigation on Android only, but they came to a head in 2012. What Apple did with iOS 6 was to replace the Google back-end to Apple Maps with its own home-grown data.

For Apple, the creation of its own mapping and routing data from scratch was a monumental undertaking, which unsurprisingly ran into some issues, especially in the early days. However, very soon I found the data to be perfectly usable in the real world, even where I live, very far from Silicon Valley, with all that entails.

That positive overall opinion does not mean that there were no annoyances. Apple Maps’ search function is very finicky, expecting names of streets and businesses to be entered exactly as written, and with an irritating tendency to provide a result, any result – even if it happens to be somewhere completely different, thousands of miles, several national borders, and sometimes even an ocean or two away. Surely some basic heuristic should be able to figure out that if I don’t specify that I want a far away result, I’m probably expecting one within a few tens of kilometres at most? This behaviour has improved over time, but is still present to a certain extent.

All apps have their foibles, and these days, the Big Three mapping services – Apple Maps, Google Maps, and Waze – are pretty close in their usability. Head-to-head comparisons reveal that Apple Maps gives the most accurate estimates of arrival times, while Waze over-promises the time savings from its shortcuts. As more and more people use Waze, those "shortcuts" are causing congestion on the suburban streets that drivers are being guided to use in place of the gridlocked highways.

Very few people make detailed comparisons of map data and navigation instructions. The main benefit people are looking for is usability. Can I tap on an address and get directions? If I connect my phone to my car, does it offer to give me directions to the next appointment in my calendar? Can I text my spouse with a detailed ETA based on actual traffic conditions?

In the modular world, such integration is harder to achieve, simply because each one of the different modules offers slightly different features, or different implementations of common features. Also, modules are constantly changing and evolving at different paces, or even disappearing entirely.

Google is the main advocate for the modular approach, and indeed often produces several competing apps and services for the very same functionality. Google Maps and Waze are increasingly overlapping with each other, for instance. Google Play Music and YouTube Music are equally hard to disentangle. And it seems that every other month brings either the launch of a new Google chat service, or the demise of one of the existing ones. In this situation, users are expected to swap modules around on a regular basis – and if the new module doesn’t offer the same functionality as the old one, or does so in a way that is different and breaks your workflow – well, tough!

For myself, I find the Apple approach preferable. When I invoke a voice assistant on my phone, I am happy to know that it’s Siri, not Alexa or Cortana or whatever Google’s assistant is called, and that my personal data are not being added to some advertising profile that is of no use to me – but that’s another rant for another day. Meanwhile, everything just works; iOS knows who my next calendar appointment is with, and that person's contact card has their office address – and so Maps can suggest a route to that address, as well as letting me easily tell my counterparts when I will arrive. Doing this with modular services is not impossible, but it takes more effort than the average person wants to deal with, while exposing them to a series of trade-offs, precisely because of the lack of separation between apps.

When it comes to maps, though, I have to add one last caveat: your mileage may vary (still not sorry).

🖼️ Photos by Capturing the human heart., Mike Enerio, and Alexander Popov on Unsplash

Once again: no, Google does not "sell our data". What it does sell to advertisers is access to certain audiences, defined by their interests, demographics, etc. It is not in Google’s interest ever to sell the data themselves; those are Google’s crown jewels, and they make most of their money by renting access to the product – but never selling the actual data. ↩

An arrangement that continues today, with Apple being handsomely compensated for keeping Google as the default search engine within iOS. ↩

Until iOS 12 Apple Maps was the only mapping app allowed to use CarPlay, though. ↩

Now that AWS re:Invent is done, conference season is over for me this year.

I feel quite virtuous, because I have managed to collect only a single vendor T-shirt and one cellphone stand all year, leaving all the other tat behind at the various shows.

The fact I’m not hauling it home doesn’t mean all of that tat doesn’t have an impact though. Here is a good roundup:

It’s not just tote bags, which only make up 8.4% of total promotional product sales. It’s also T-shirts, which represent more than a quarter of sales; writing instruments, which make up 6.1%; and various tech accessories, like USB drives, which make up 7.5%.

The promotional products industry in the United States is worth $24 billion and has grown by 2.5% over the last five years. There are 26,413 businesses in the space, which employs 392,820 people, according to the most recent figures. While cheap swag is popular across industries, education, healthcare, insurance, nonprofits, marketing companies, and technology are the biggest consumers of these items.

As we all start to plan the 2019 shows, here are some suggestions for event planning teams to minimise the footprint of all this activity.

For a start, while a few people still genuinely prefer hard copy materials, most of the paper brochures handed out at trade show booths go straight into the nearest recycling bin. Instead of scaring a bunch of trees, why not have a panel in the booth with a row of QR codes so that attendees can grab electronic copies of the materials? Or combine that with a station where they can email themselves relevant material directly from the show floor.1

I would suggest not to have any give-aways that are specific to one show. I have seen all sorts of ridiculous hats, wristbands, and even headbands. These are even more likely to be left behind in a hotel room than the general run of the mill giveaways.

T-shirts are a mixed bag. Some manage to achieve the status of becoming actual collectibles – see e.g. the Splunk shirts, at least a few years ago. Most however will at best be used for decorating, or as sleeping attire for the female attendees. Probably not where you wanted your logo displayed: the audience is generally very small, and it’s probably too dark to read anyway.

More positively, you can do something that is specific to the location of the show; maybe you could raffle off tickets to Cirque du Soleil for a show in Las Vegas, or a tour of the city somewhere like London. At smaller events where most attendees will be staying at the same hotel, you could also offer hotel vouchers for spa treatments or room upgrades.

People do like a little tchotchke, but try to make it something useful – and not fake-useful, meaning no 256MB USB keys, low-quality tote bags, or yet another fidget spinner. Instead, my suggestion is to align the giveaway to your brand identity: pocket tools or batteries for "useful", drinks for "refreshing", and so on.

Finally, I can’t claim credit for this one, but there was an excellent suggestion on Twitter during AWS re:Invent:

Okay, real talk #AWSreinvent expo vendors: why does no one have small travel pillow swag?

— George Miranda (@gmiranda23) November 27, 2018

“Rest easy, {product} has you covered”

“Don’t let your cloud keep you up at night, use {product}”

“Relax, you’re using {product}”

I expect pillows next year.

This seems like an excellent idea: people will genuinely want to use the pillow, and so provided your logo isn’t too tasteless, they will be reminded of you every time they travel. For an example of a company doing this right, AWS themselves always manage to have excellent hoodies for re:Invent attendees: high quality, and with branding that is recognisable but sufficiently subtle not to be in your face.

See you on the show floor in 2019!

Yes, eagle-eyed events people, this would indeed give you an extra opportunity to get their contact details – but mind that GDPR! ↩

Last week was AWS re:Invent, and I’m still dealing with the email hangover.1 AWS always announce a thousand and one new offerings and services at their show, and this year was no exception. However, there is one announcement that I wanted to reflect upon briefly, out of however many there were during the week.

AWS Outposts are billed as letting users "Run AWS infrastructure on-premises for a truly consistent hybrid experience". This of course provoked a certain amount of hilarity in the parts of Twitter that have been earnestly debating the existence of hybrid cloud since the term was first coined.

It could just be a big empty box with an LED on it and an internet connection inside, that way you get all the services 🙂

— James Tomkins 💙 (@jamestomkins) November 29, 2018

On the surface, it might indeed seem somewhat strange for AWS, the archetypal public cloud in most people’s minds, to start offering hardware to be deployed on customers’ premises. However, to me it makes perfect sense.

Pace some ten-year-old marketing slogans which have not aged well, most companies do not start out with a hybrid cloud strategy. Instead, they find themselves forced by circumstances to formulate one in order to deal with all of the various departments that are out there doing their own thing. In this situation, the hybrid cloud strategy is simply recognition that different teams have different requirements and have made their own decisions based on those. All that corporate IT can do is try to gain overall visibility and attempt to ensure that all the various flavours of compute infrastructure are at least being used in ways which are sane, secure, and fiscally responsible (the order of the priorities may change, but that’s the list).

Some of the more wild-eyed predictions around hybrid cloud instead expected that workloads would be easily moved, not only between on- and off-premises compute infrastructure, but even between different cloud providers. In fact, it would be so easy that it would be possible to make minute-by-minute assessments of the cost of running workloads with different providers, and move them from one to another in order to take advantage of lower prices.

Obviously, that did not happen.

For the cloud broker model to work, several laws of both economics and physics would have to be suspended or circumvented, and nobody seems to have made the requisite breakthroughs.

To take just a few of the more obvious objections:

Moving any meaningful amount of data around the public internet still takes time. If you are used to your local 100 Gb-E LAN, it can be easy to forget this, but it is going to be a factor out there in the wild wild Web. This objection was obvious when we were talking about moving monolithic VMs around, but even if you assume truly immutable infrastructure, you are still going to have to shift at least some snapshot of the application state, and that adds up fast – let alone the rate of configuration drift of your "immutable" infrastructure with each new micro-release.

The units of measure of different cloud providers are not easily comparable. How does the performance of an AWS M5 instance compare to an Azure Dv2-series? Well, you’d better know before you move production over there… And AWS has 24 instance types, whereas Azure has 7 different series, each with sub-types and options – and let’s not even talk about all the weird and wonderful single-use configurations in your local VMware or Openstack service catalogue! How portable is your workload, really?

Or let’s take it from the other side: assume you have carefully architected your thing to use only minimum-common-denominator components that are, if not identical, at least similar enough across all of the various substrates they might find themselves running on. By definition, this means that you are not taking full advantage of the more advanced capabilities of each of those platforms. This limitation is not only at the ingredient level; you also have to make worst-case assumptions about the sorts of network bandwidth and latency you might have access to, or the sort of regulatory and policy compliance environment that you might find yourself operating within.

For all of these reasons and more, the dream of real-time cloud pricing arbitrage died a quick death, regardless of whether individual companies might use different cloud providers in various parts of their business.

Amazon Outposts is not that. For a start, despite running physically on the customer’s premises, it is driven entirely from the (remote) AWS control plane. Instead, it has the potential to address concerns about physical location together with associated concerns about latency and legal jurisdiction. Being AWS (with some help from VMware) it avoids the concern about different units of measure. For now, it only goes part of the way to resolving the final question about minimum common denominator ingredients, since at launch it only supports EC2. Additional features are expected shortly, however, especially including various storage options.

So yes, hybrid cloud. Turns out, it’s not only still a thing, but you can even get it from AWS. Who’d have thunk it?

I managed to avoid any hangovers of the alcoholic variety; staying well hydrated in Las Vegas is good for multiple purposes. My inbox, however, is a mess. ↩

Many petrolheads are worried that self-driving cars will kill the idea itself of the car. Personally, I’m not that worried about that; horses have not been a primary means of transport for maybe a century, and yet there still seem to be plenty of enthusiasts who enjoy them. I rode my bike side-by-side with a horse just last weekend.

No, my main concern is about the process of getting to fully self-driving cars. Today, we have cars with all sorts of safety features such as radar cruise control and lane-departure warnings. These already add up to a limited self-driving capability – level 2 or perhaps even 3 in the NHTSA definition. I have used some of this functionality myself on the German Autobahn, with my hired Volvo staying in its lane, following curves in the road, and accelerating or braking with the traffic, including coming to a complete stop.

I was never able to get out a book or just climb into the back seat for a nap, though. I always had to remain alert and engaged in case of any failure of the self-driving systems. Ultimately, I found this more wearing than just driving myself, and so I disengaged all the systems, got off the clogged-up Autobahn, and found myself a twisty and more engaging alternative route where I could concentrate fully on the driving.

This is the "uncanny valley" problem of self-driving cars: in order to get to full autonomy, we have to deal with a transition period where the automated systems are not yet good enough to do the job, but they are already good enough for drivers to become distracted and disengaged from the process of driving. The risk is that when the systems fail, the driver is not able to re-establish situational awareness and take control quickly enough to avoid an incident. We saw this scenario play out with tragic consequences when a self-driving Uber car struck and killed a woman earlier this year.

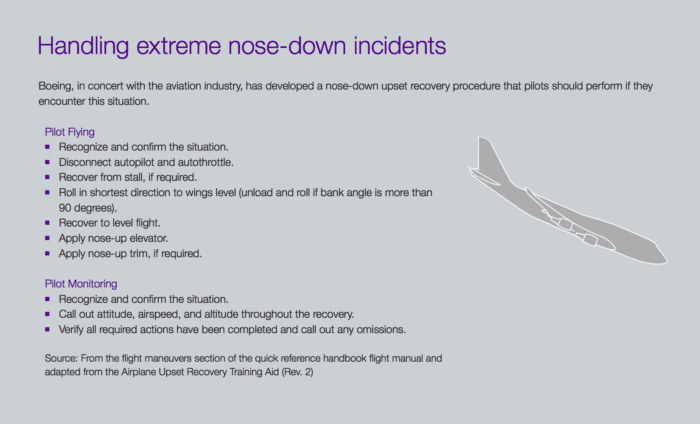

This problem of operator attention is of course not unique to cars, and may in fact have played a part in the tragic Lion Air crash in Indonesia. As part of the investigation of that crash, it was uncovered that a faulty air-speed sensor may have been the proximate cause of the accident, leading to the plane’s avionics mis-identifying the situation as a stall and putting the nose of the plane down to recover the speed necessary to get out of that stall.

The FAA has now issued a directive to operators of the plane to update their manuals. The linked article includes this image, purportedly from an internal Boeing magazine, describing the steps involved in identifying and correcting this situation:

You’re a pilot, climbing on autopilot on a routine departure – so you don’t have much airspeed or altitude to play with. Suddenly for no apparent reason the plane pitches nose-down. You have to diagnose the problem correctly, disengage a bunch of systems, and recover manual control. It’s a hard task, even for trained aircraft pilots.

Now imagine the same situation in a self-driving car. You’re on the phone, thinking about something else, and suddenly the car is drifting across lane markings, straight towards a concrete highway divider.

How do you rate your chances?

It is true that these systems will only improve with real-world usage and with more data to learn from, but their marketing and usage need to be aligned to their actual capabilities and failure modes, not what we wish they would be or what they might be in ideal conditions. New interface paradigms may also be required to set operators’ experience accordingly.

Until we get there, a sensible minimum standard seems to be that we should not expect drivers to do anything as a matter of course that is difficult even for trained airline pilots.