One of the most powerful memes in tech is the Innovator’s Dilemma. Professor Clayton Christensen’s theory posits moves from integrated products to modularised ones, driven by waves of innovation at different levels. The world of tech swings regularly between these poles of integration and modularisation. Sometimes the whole industry moves at once, as in the ongoing move away from modular desktop computers and towards all-in-one laptops, tablets, and hybrids of the two, with modularisation moving to other levels of the stack. At other times competing models are in play at the same time, with little agreement as to which is better.

Apple is often cited as a counter-example, the archetypal integrated company that defies the conventional wisdom of modularisation exemplified by the infinite variety of the Android platform. One counter-counter-example that often comes up is Maps, and I would like to take a moment to explore (sorry – not sorry) this point.

From launch, Apple Maps was derided as not just a failure, but an actively wrong and misguided choice by Apple. It even gets brought up as the ultimate negative example, as in this M G Siegler piece about Instagram data: "The data makes Apple Maps look like a pristine globe of information". Google had mapping and navigational data that were objectively better, the thinking went, so Apple should simply continue to adopt this external module within their own platform, regardless of consequences.

There is a philosophical aspect to this debate, of course, which may have more currency today than it did at the time. As the famous adage goes, if you’re not paying, you’re the product. Certainly with Google Maps, gathering and analysing users’ personal data was very much a key goal of Google’s, both for the altruistic reason of improving mapping and routing data, and for the more irritating one of contributing to the ever more detailed profiles it keeps of all of us in order to pitch us en masse to advertisers.

Apple had never been entirely comfortable with this situation, and exacted large payments from Google in return for its privileged position within iOS. With the launch of iOS 6, Apple deprecated the use of Google’s data as a source for the built-in Maps application.

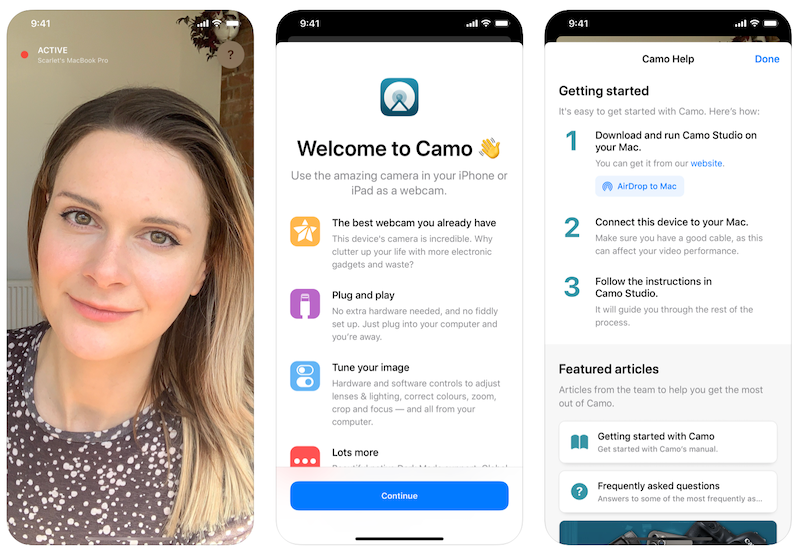

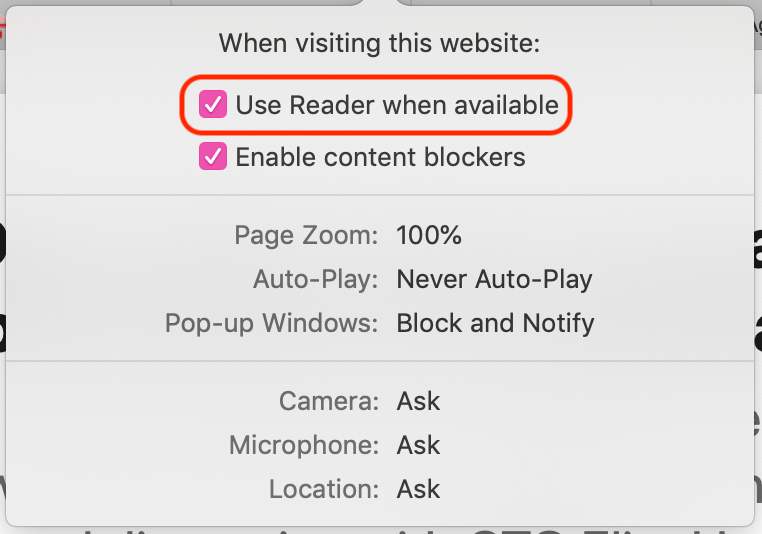

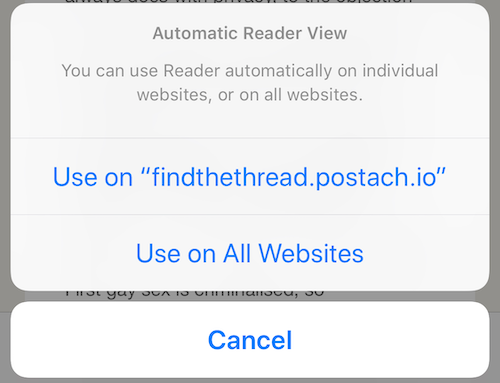

Note that Google’s own Maps app was never banned from Apple’s iOS or from its accompanying App Store. The difference between the systemwide Apple Maps and Google Maps (or any other third-party mapping app, for that matter) was the integration with all other apps that needed mapping data. In much the same way that tapping on a link would open the built-in Safari web browser, tapping on an address would open the built-in Apple Maps app. Using a third-party web browser, mapping app, or chat/IM or email client, required explicit action by the user each and every time.

Apple’s Walled Garden… Orchard?

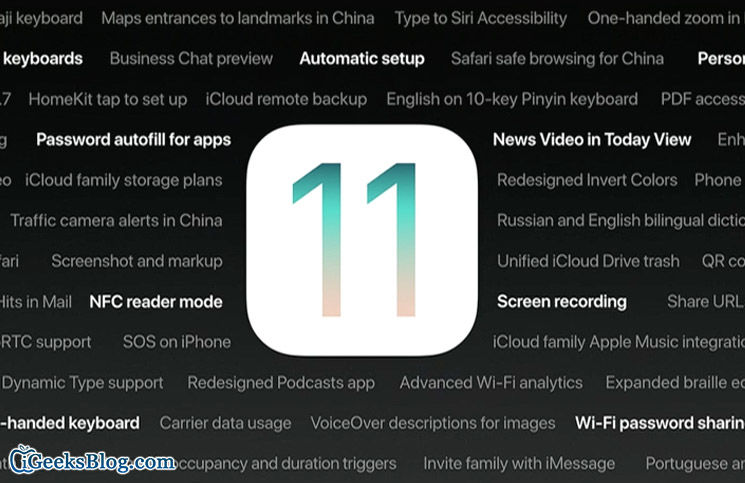

Some users objected on grounds of principle to the deep integration of first-party apps and the consequent exclusion of third-party ones. Windows desktop operating systems had trained users to install any number of third-party utilities and widgets, either as replacements for system components or to extend native functionality. iOS did not work this way.

Apple had always preferred an integrated approach, producing both its own hardware and its own operating system ever since the original Apple ][, and complementing that with suites of its own applications. In the 90s I had an Apple StyleWriter printer attached to my Macintosh LC, which I interacted with through an Apple monitor, keyboard, and mouse. Displayed on that monitor was a ClarisWorks document, which was of course owned by Apple as well. Sure, it was possible to run Microsoft Office, and even (for a while) Internet Explorer. In fact, in the doldrums of the early 2000s, after the demise of Cyberdog, Apple’s first attempt at a web browser, and before the rise of Safari with OS X, Microsoft’s was the best browser option on the Mac.

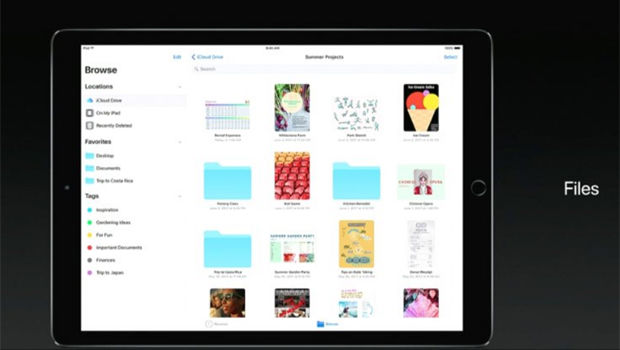

This moment of dependence on third parties had its benefits – keeping the company alive at a very difficult time, for instance – but robbed Apple of ultimate control. As owners increasingly expected to be able to personalise the behaviour of their Macs with custom extensions, those systems became increasingly unstable. The introduction of OS X addressed many of those issues by replacing the creaking foundations of classic Mac OS with the Darwin kernel, but still gave users quite a lot of control. When it came time to launch iOS, however, Apple’s pre-existing philosophical bent towards opinionated design combined with the very real limitations of the hardware of the day to produce a "walled garden" where only Apple’s apps would run. The original iPhone did not even have an App Store; instead, Apple envisioned that third-party functionality would be provided through web apps (never mind that EDGE connectivity was not really up to the job, even in 2006).

Play Nice In The Sandbox

Apple did eventually relent and allow third-party apps to run on iPhones, but always in a very controlled manner, with strict sandboxing preventing apps from interfering with each other. This separation also prevented apps from interacting with each other at all, to the point that copy&paste functionality only arrived on iOS with 3.0, released in 2009, and was heralded as a major innovation when it did.

Even then, Apple maintained strict control over core functionality, giving users no ability to replace the standard web browser, email client, to-do list, and more. The Maps app was also part of this list, but used third-party data from Google for its functionality. Tensions had been brewing over this arrangement for a couple of years already, with Google introducing turn-by-turn navigation on Android only, but they came to a head in 2012. What Apple did with iOS 6 was to replace the Google back-end to Apple Maps with its own home-grown data.

For Apple, the creation of its own mapping and routing data from scratch was a monumental undertaking, which unsurprisingly ran into some issues, especially in the early days. However, very soon I found the data to be perfectly usable in the real world, even where I live, very far from Silicon Valley, with all that entails.

That positive overall opinion does not mean that there were no annoyances. Apple Maps’ search function is very finicky, expecting names of streets and businesses to be entered exactly as written, and with an irritating tendency to provide a result, any result – even if it happens to be somewhere completely different, thousands of miles, several national borders, and sometimes even an ocean or two away. Surely some basic heuristic should be able to figure out that if I don’t specify that I want a far away result, I’m probably expecting one within a few tens of kilometres at most? This behaviour has improved over time, but is still present to a certain extent.

All apps have their foibles, and these days, the Big Three mapping services – Apple Maps, Google Maps, and Waze – are pretty close in their usability. Head-to-head comparisons reveal that Apple Maps gives the most accurate estimates of arrival times, while Waze over-promises the time savings from its shortcuts. As more and more people use Waze, those "shortcuts" are causing congestion on the suburban streets that drivers are being guided to use in place of the gridlocked highways.

So Do I Want Modular Or Integrated Maps?

Very few people make detailed comparisons of map data and navigation instructions. The main benefit people are looking for is usability. Can I tap on an address and get directions? If I connect my phone to my car, does it offer to give me directions to the next appointment in my calendar? Can I text my spouse with a detailed ETA based on actual traffic conditions?

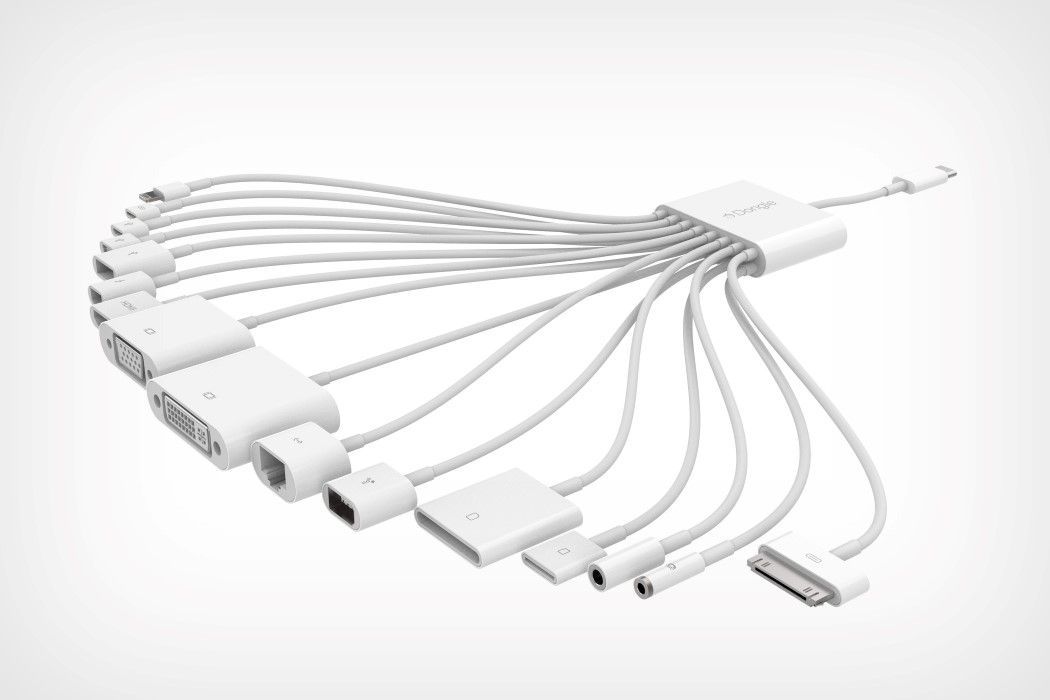

In the modular world, such integration is harder to achieve, simply because each one of the different modules offers slightly different features, or different implementations of common features. Also, modules are constantly changing and evolving at different paces, or even disappearing entirely.

Google is the main advocate for the modular approach, and indeed often produces several competing apps and services for the very same functionality. Google Maps and Waze are increasingly overlapping with each other, for instance. Google Play Music and YouTube Music are equally hard to disentangle. And it seems that every other month brings either the launch of a new Google chat service, or the demise of one of the existing ones. In this situation, users are expected to swap modules around on a regular basis – and if the new module doesn’t offer the same functionality as the old one, or does so in a way that is different and breaks your workflow – well, tough!

For myself, I find the Apple approach preferable. When I invoke a voice assistant on my phone, I am happy to know that it’s Siri, not Alexa or Cortana or whatever Google’s assistant is called, and that my personal data are not being added to some advertising profile that is of no use to me – but that’s another rant for another day. Meanwhile, everything just works; iOS knows who my next calendar appointment is with, and that person's contact card has their office address – and so Maps can suggest a route to that address, as well as letting me easily tell my counterparts when I will arrive. Doing this with modular services is not impossible, but it takes more effort than the average person wants to deal with, while exposing them to a series of trade-offs, precisely because of the lack of separation between apps.

When it comes to maps, though, I have to add one last caveat: your mileage may vary (still not sorry).

🖼️ Photos by Capturing the human heart., Mike Enerio, and Alexander Popov on Unsplash