As the token European among the Roll For Enterprise hosts, I'm the one who is always raising the topic of privacy. My interest in privacy is partly scarring from an early career as a sysadmin, when I saw just how much information is easily available to the people who run the networks and systems we rely on, without them even being particularly nosy.

Because of that history, I am always instantly suspicious of talk of "personalising the customer experience", even if we make the charitable assumption that the reality of this profiling is more than just raising prices until enough people balk. I know that the data is unquestionably out there; my doubts are about the motivations of the people analysing it, and about their competence to do so correctly.

Let's take a step back to explain what I mean. I used to be a big fan of Amazon's various recommendations, for products often bought with the product you are looking at, or by the people who looked at the same product. Back in the antediluvian days when Amazon was still all about (physical) books, I discovered many a new book or author through these mechanisms.

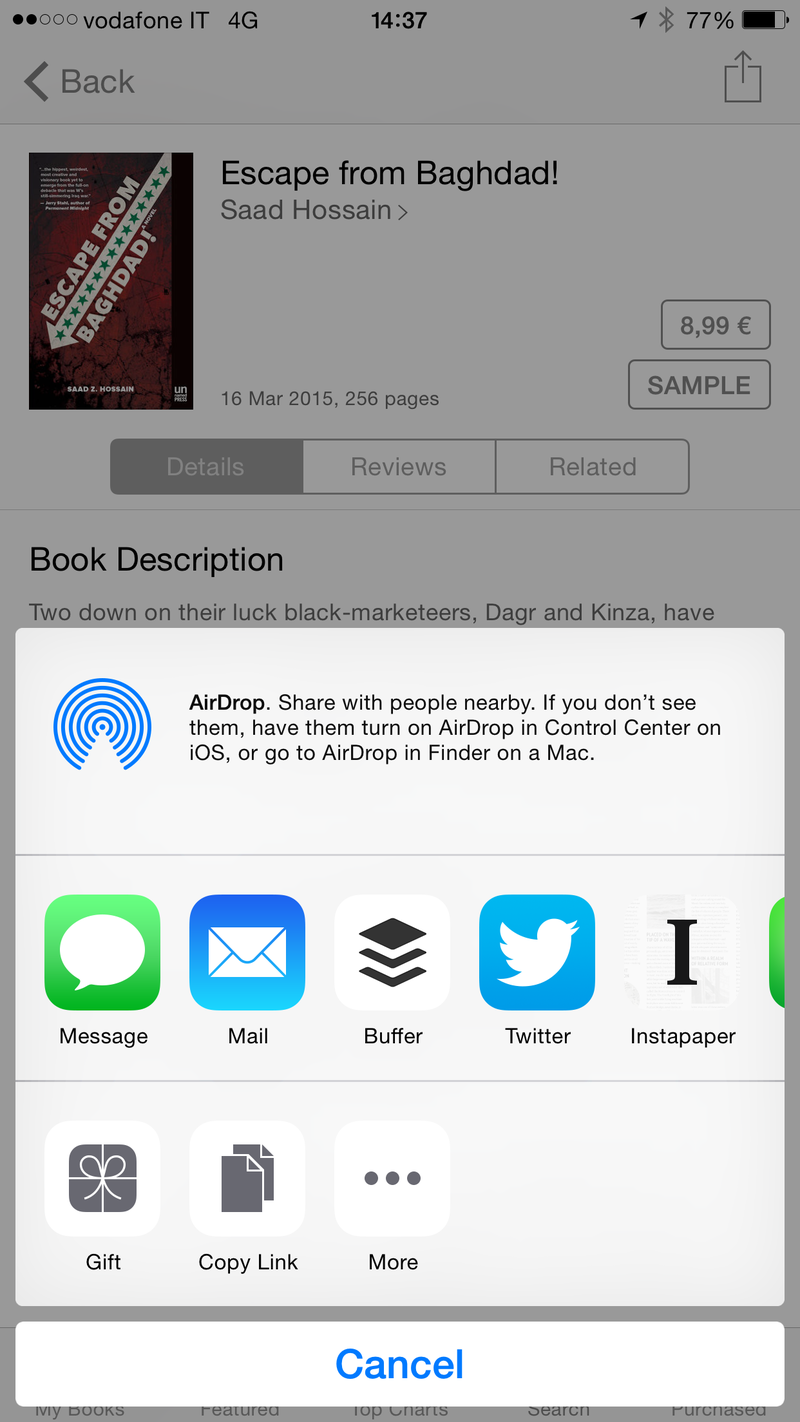

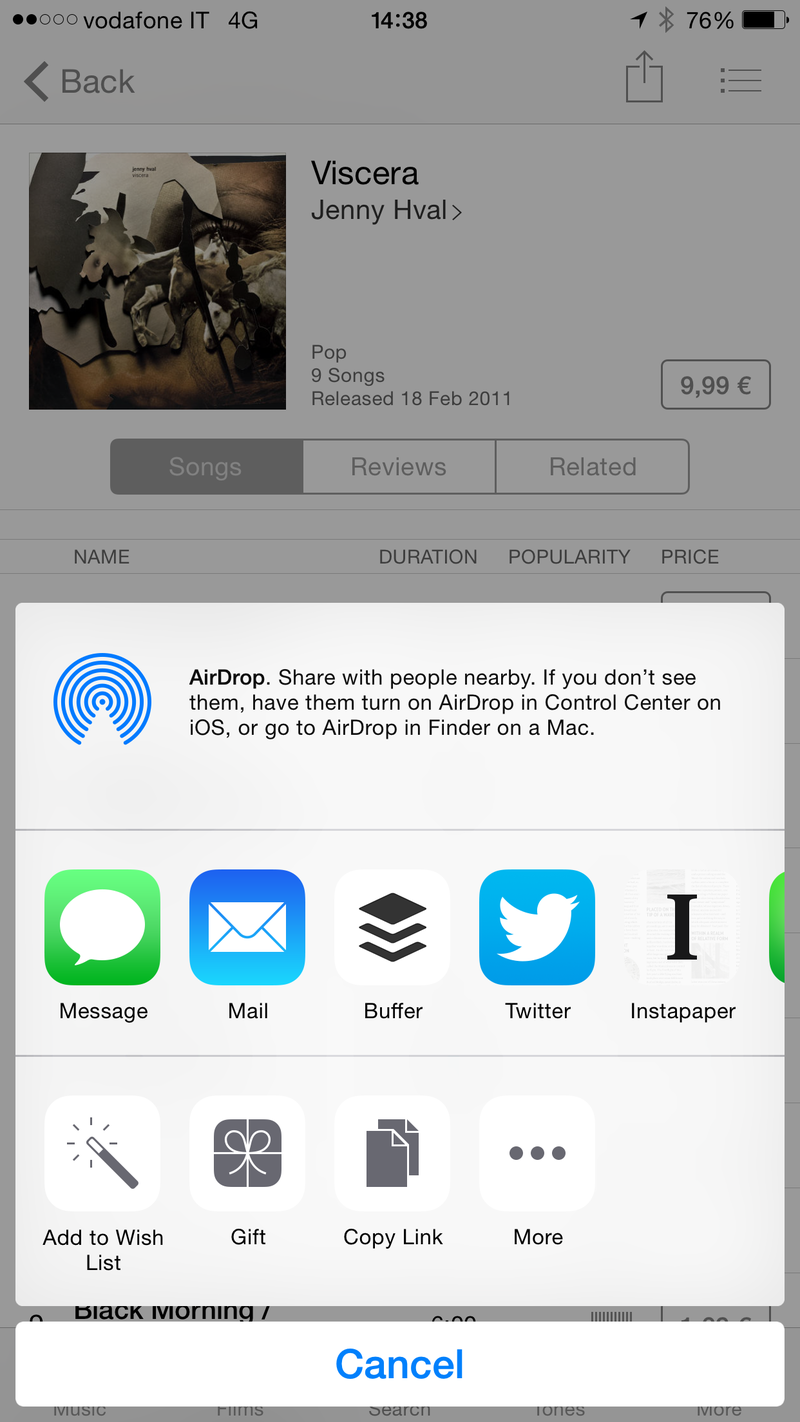

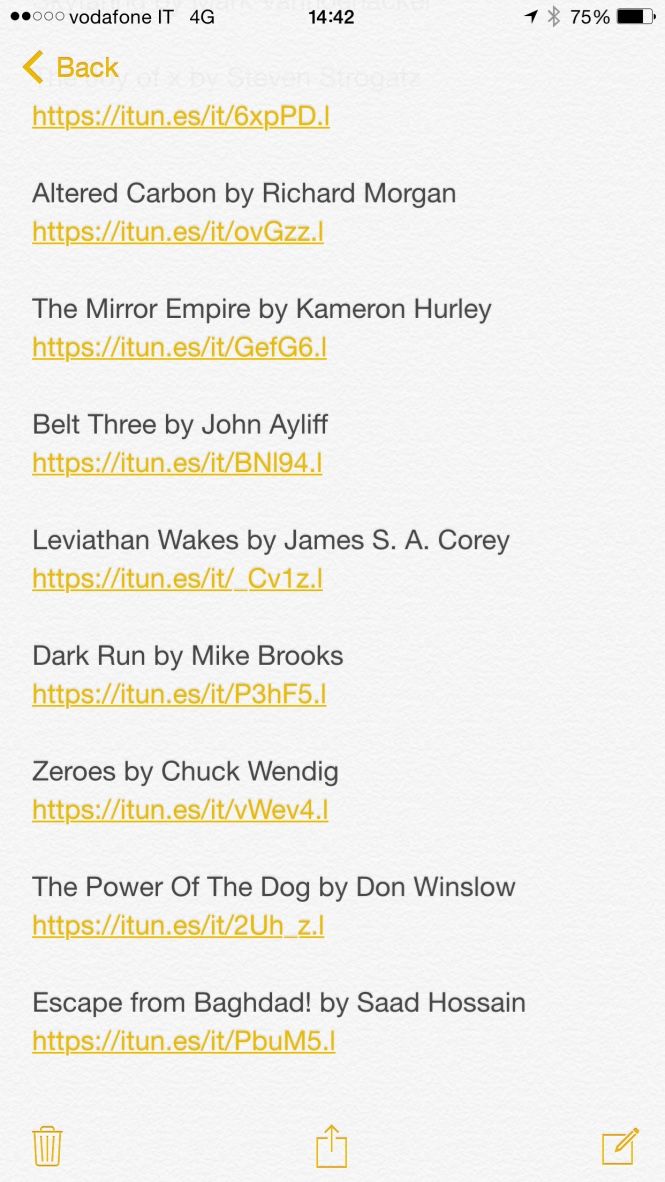

One of my favourite aspects of Amazon's recommendation engine was that it didn't try to do it all. If I bought a book for my then-girlfriend, who had (and indeed still has, although she is now my wife) rather different tastes from me, this would throw the recommendations all out of whack. However, the system was transparent and user-serviceable. Amazon would show me transparently why it had recommended Book X, usually because I had purchased Book Y. Beyond showing me, it would also let me go back into my purchase history and tell it not to use Book Y for recommendations (because it was not actually bought for me), thereby restoring balance to my feed. This made us both happy: I got higher-quality recommendations, and Amazon got a more accurate profile of me, that it could use to sell me more books — something it did very successfully.

Forget doing anything like that nowadays! If you watch Netflix on more than one device, especially if you ever watch anything offline, you'll have hit that situation where you've watched something but Netflix doesn't realise it or won't admit it. And can you mark it as watched, like we used to do with local files? (insert hollow laughter here) No, you'll have that "unwatched" episode cluttering up your "Up next" queue forever.

This is an example of the sort of behaviour that John Siracusa decried in his recent blog post, Streaming App Sentiments. This post gathers responses to his earlier unsolicited streaming app spec, where he discussed people's reactions to these sorts of "helpful" features.

People don’t feel like they are in control of their "data," such as it is. The apps make bad guesses or forget things they should remember, and the user has no way to correct them.

We see the same problem with Twitter's plans for ever greater personalisation. Twitter defaulted to an algorithmic timeline a long time ago, justifying the switch away from a simple chronological feed with the entirely true fact that there was too much volume for anyone to be a Twitter completist any more, so bringing popular tweets to the surface was actually a better experience for people. To repeat myself, this is all true; the problem is that Twitter did not give users any input into the process. Also, sometimes I actually do want to take the temperature of the Twitter hive mind right now, in this moment, without random twenty-hour-old tweets popping up out of sequence. The obvious solution of giving users actual choice was of course rejected out of hand, forcing Twitter into ever more ridiculous gyrations.

The latest turn is that for a brief shining moment they got it mostly right, but hilariously and ironically, completely misinterpreted user feedback and reversed course. So much for learning from the data… What happened is that Twitter briefly gave users the option of adding a "Latest Tweets" tab with chronological listing alongside the algorithmic default "Home" tab. Of course such an obviously sensible solution could not last, for the dispiriting reason that unless you used lists, the tabbed interface was new and (apparently) confusing. Another update therefore followed rapidly on the heels of the good one, which forced users to choose between "Latest Tweets" or "Home", instead of simply being able to have both options one tap apart.

Here's what it boils down to: to build one of these "personalisation" systems, you have to believe one of two things (okay, or maybe some combination):

- You can deliver a better experience than (most) users can achieve for themselves

- Controlling your users' experience benefits you in some way that is sufficiently important to outweigh the aggravation they might experience

The first is simply not true. It is true that it is important to deliver a high-quality default that works well for most users, and I am not opposed in principle to that default being algorithmically-generated. Back when, Twitter used to have "While you were away" section which would show you the most relevant tweets since you last checked the app. I found it a very valuable feature — except for the fact that I could not access it at will. It would appear at random in my timeline, or then again, perhaps not. There was no way to trigger it manually, or any place where it would appear reliably and predictably. You just had to hope — and then, instead of making it easier to access on demand, Twitter killed the entire feature in an update. The algorithmic default was promising, but it needed just a bit more control to make it actually good.

On the other hand, I quite like “while you were away” and wish I could access it on demand, instead of being reduced to hoping it shows up, like a peasant praying for rain.

— Dominic 🇪🇺🇺🇦🏳️🌈 (@dwellington) June 29, 2021

This leads us directly to the second problem: why not show the "While you were away" section on demand? Why would Netflix not give me an easy way to resume watching what I was watching before? They don't say, but the assumption is that the operators of these services have metrics showing higher engagement with their apps when they deny users control. Presumably what they fear is that, if users can just go straight to the tweets they missed or the show they were watching, they will not spend as much time exploring the app, discovering other tweets or videos that they might enjoy.

What is forgotten is that "engagement" just happens to be one metric that is easy to measure — but the ease of measurement does not necessarily make it the most important dimension, especially in isolation. If that engagement is me scrolling irritably around Twitter or Netflix, getting increasingly frustrated because I can't find what I want, my opinion of those platforms is actually becoming more corroded with every additional second of "engagement".

There is a common unstated assumption behind both of the factors above, which is that whatever system is driving the personalisation is perfect, both unbreakable in its functioning and without corner cases that may deliver sub-optimal results even when the algorithm is working as designed. One of the problems with black-box systems is that when (not if!) they break, users have no way to understand why they broke, nor to prevent them breaking again in the future. If the Twitter algorithm keeps recommending something to me, I can (for now) still go into my settings, find the list of interests that Twitter has somehow assembled for me, and delete entries until I get back to more sensible recommendations. With Netflix, there is no way for me to tell it to stop recommending something — presumably because they have determined that a sufficient proportion of their users will be worn down over time, and, I don't know, whatever the end goal is — watch Netflix original content instead of something they have to pay to license from outside.

All of this comes back to my oft-repeated point about privacy: what is it that I am giving up my personal data in exchange for, in the end? The promise is that all these systems will deliver content (and ads)(really it's the ads) that are relevant to my interests. Defenders of surveillance capitalism will point out that profiling as a concept is hardly new. The reason you find different ads in Top Gear Magazine, in Home & Garden, and in Monocle, is that the profile for the readership is different for each publication. But the results speak for themselves: when I read Monocle, I find the ads relevant, and (given only the budget) I would like to buy the products featured. The sort of ads that follow me around online, despite a wealth of profile information generated at every click, correlated across the entire internet, and going back *mumble* years or more, are utterly, risibly, incomprehensibly irrelevant. Why? Some combination of that "we know better" attitude, algorithmic profiling systems delivering less than perfect results, and of course, good old fraud in the adtech ecosystem.

So why are we doing this, exactly?

It comes back to the same issue as with engagement: because something is easy to measure and chart, it will have goals set against it. Our lives online generate stupendous volumes of data; it seems incredible that the profiles created from those megabytes if not gigabytes of tracking data have worse results than the single-bit signal of "is reading the Financial Times". There is also the ever-present spectre of "I know half of my ad spending is wasted, I just don't know which half". Online advertising with its built-in surveillance mechanisms holds out the promise of perfect attribution, of knowing precisely which ad it was which caused the customer to buy.

And yet, here we are. Now, legislators in the EU, in China, and elsewhere around the world are taking issue with these systems, and either banning them outright or demanding they be made transparent in their operation. Me, I'm hoping for the control that Amazon used to give me. My dream is to be able to tell YouTube that I have no interest in crypto, and then never see a crypto ad again. Here, advertisers, I'll give you a freebie: I'm in the market for some nice winter socks. Show me some ads for those sometime, and I might even buy yours. Or, if you keep pushing stuff in my face that I don't want, I'll go read a (paper) book instead. See what that does for engagement.

🖼️ Photos by Hyoshin Choi and Susan Q Yin on Unsplash