Here's a blog post I wrote back in 2015 for my then-employer that I was reminded of while recording the latest episode of the Roll For Enterprise podcast. Since the original post no longer seems to be available via the BMC web site, I assume they won't mind me reposting it here, with some updated commentary.

There has been a certain amount of excitement in the news media, as someone purportedly associated with ISIL has taken over and defaced US Central Command's Twitter account. The juxtaposition with recent US government pronouncements on "cyber security" (ack) is obvious: Central Command’s Twitter Account Hacked…As Obama Speaks on Cybersecurity.

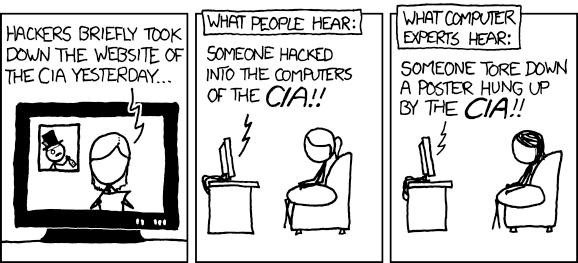

The problem here is the usual confusion around IT in general, and IT security in particular. See for instance CNN:

The Twitter account for U.S. Central Command was suspended Monday after it was hacked by ISIS sympathizers -- but no classified information was obtained and no military networks were compromised, defense officials said.

To an IT professional, even without specific security background, this is kind of obvious.

Penny Arcade, Brains With Urgent Appointments

Penny Arcade, Brains With Urgent Appointments

However, there is a real problem here. IT professionals also have a blind spot here: they don't think of things like Twitter accounts when they are securing IT infrastructure. This oversight can expose organisations to serious problems.

One way this can happen is credential re-use and leaking in general. Well-run organisations will use secure password-sharing services such as LastPass, but many times without IT guidance teams might instead opt for storing credentials in a spreadsheet, as we now know happened at Sony. If someone got their hands on even one set of credentials, what other services might they be able to unlock?

The wider issue is the notion of perimeter defence. IT security to date has been all about securing the perimeter - firewalls, DMZs, NAT, and so on. Today, though, what is the perimeter? End-user services like Dropbox, iCloud, or Google Docs, as well as multi-tier enterprise applications, span back and forth across the firewall, with data stored and code executed both locally and remotely.

I don't mean to pick on Sony in particular - they are just the most recent victims - but their experience has shown once and for all that focusing only on the perimeter is no longer sufficient. The walls are porous enough that it is no longer possible to assume that bad guys are only outside. Systems and procedures are needed to detect anomalous activity inside the network, and once that occurs, to handle it rapidly and effectively.

This cannot happen if IT is still operating as "the department of NO", reflexively refusing user requests out of fear or potential consequences. If the IT department tries to ban everything, users will figure out a way to go around the restrictions to achieve their goals. The risk then is that they make choices which put the entire organisation and even its customers at risk. Instead, IT needs to engage with those users and find creative, novel ways to deliver on their requirements without compromising on their mandate to protect the organisation.

While corporate IT cannot be held responsible for the security of services such as Twitter, they can and should advise social-media teams and end-users in general on how to protect all of their services, inside and outside the perimeter.

There are a still a lot of areas where IT is focused on perimeter defence. Adopting Okta or another SSO service is not a panacea; you still do need to consider what would happen when (not if) someone gets inside the first layer of defence. How would you detect them? How would you stop them?

The Okta breach has also helpfully provided an example of another important factor in security breaches: comms. Okta's comms discipline has not been great, reacting late, making broad denials that they later had to walk back, and generally adding to the confusion rather than reducing it. Legislation is being written around the world (with the EU as usual taking the lead) to mandate disclosure in situations like these, which may focus minds — but really, if you're not sufficiently embarrassed as a security provider that a bunch of teenagers were apparently running around your network for at least two weeks without you detecting them, you deserve all the fines you're going to get.

These are no longer purely tech problems. Once you get messy humans in the mix, the conversation changes from "how many bits of entropy does the encryption algorithm need" to "what is the correct trade-off between letting people get their jobs done and ensuring a reasonable level of security, given our particular threat model". Working with humans means communicating with them, so you’d better have a plan ready to go for what to say in a given situation. Hint: blanket denials early on are generally a bad idea, leaving hostages to fortune unnecessarily.

Have a plan ready to go for what you will say in a given situation (including what you may be legally mandated to disclose, and on what timeframe), and avoid losing your customers’ trust. Believe me, that’s one sort of zero trust that you don’t want!