The thing that really annoys me about the death of Twitter1 is that there is no substitute. As I wrote:

none of these upstart services will become the One New Twitter. Twitter only had the weight it had because it was (for good and ill) the central town square where all sorts of different communities came together. With the square occupied by a honking blowhard and his unpleasant hangers-on, people have dispersed in a dozen different directions, and I very much doubt that any one of the outlet malls, basement speakeasies, gated communities, and squatted tenements where they gather now can accomodate everyone who misses what Twitter was.

It’s worth unpacking that situation to understand it properly. Twitter famously had not been growing for a long time, leading users to speculate that:

Maybe we already saw the plateau of the microblog, and it turns out that the total addressable market is about the size that Twitter peaked at. It is quite possible that Twitter did indeed get most of the users who like short text posts, as opposed to video (Tik Tok), photo (Instagram), or audio.

In their desperation to resume growing, Twitter started messing with users’ timelines, adding algorithmic features that were supposedly designed to help users see the best content — but of course, being Twitter, they went about it in a ham-fisted way and pissed off all the power users instead of getting them excited.

The thing is, Twitter is far from the only social network to fail to land the tricky transition to an algorithmic timeline. All of the big networks are running scared of the Engagement that TikTok is able to bring, but they seem to have fundamentally misunderstood their respective situations.

All of the first-generation social networks — Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn — rely on the, well, network as the key. You will see posts from people you are connected to, and in turn the people who are connected to you will see your posts. Twitter was always at a disadvantage here, because Facebook and LinkedIn built on existing networks: family and friends for Facebook, and work colleagues and acquaintances for LinkedIn. Twitter always had a "where do I start from?" problem: when you signed up, you were presented with a blank feed, because you were not yet following anybody.

Twitter flailed about trying to figure out how to recommend accounts to follow, but never really cracked that Day One problem, which is a big part of the reason why its growth plateaued2: Twitter had already captured all of the users who were willing to go through the hassle of figuring that out, building their follow graph, and then pruning it and maintaining it over time. Anyone less committed bounced off the vertical cliff face that Twitter offered in lieu of an on-ramp.

The Algorithm Shall Save Us All!

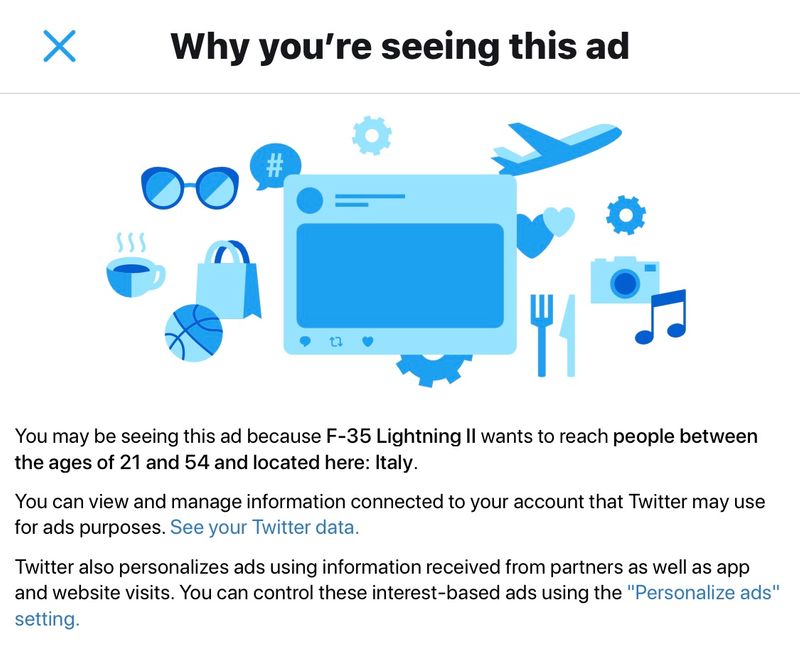

TikTok was the first big network to abandon that mechanism, and for good reason: at this point, all the other networks guard their users’ social graphs jealously for themselves. It is hard to bootstrap a social network like that from nothing. Instagram famously got its start by piggybacking on Twitter, but that’s a move you can only pull off once. Instead, TikTok went fully algorithmic: what you see in your feed is determined by the algorithm, not by whom you are connected to. The details of how the algorithm actually works are secret, controversial, and constantly changing anyway, but at a high level it’s some combination of your own past activity (what videos you have watched), the activity of people like you, and some additional weighting that the network applies to show you more videos that you might like to watch.

This means that a new account with no track record and no following will be shown a feed full of videos when they first sign in. The quality might initially be a bit hit or miss, but it will refine rapidly as you use the platform. In the same way, a good video from a new account can break out and go viral without that account having to build a following first, in the way they would have had to on the first-wave social networks.

When people started talking about algorithmic timelines like this, Twitter thought they had finally struck gold: they could recommend good tweets, whether they were from someone the user followed or not. This would fill those empty timelines, and help onboard2 new users.

The problem is that users who had put in the effort to build out their graph placed a lot of value in it, and were incandescently angry when Twitter started messing with it. I liked Old Twitter because I had tuned it, over more than a decade, to be exactly what I wanted it to be, and I know a lot better than some newly-hatched algorithm what sort of tweets I want to see in my timeline.

An algorithmic timeline doesn’t have to be bad, mind; Twitter’s first foray into this domain was a feature called "While you were away" that would show you half a dozen good tweets that you might have missed since you last checked the app. This was a great feature that addressed a real user problem: once you follow more than a few accounts, it’s no longer possible to be a "timeline completionist" and read every tweet. Especially once you factor in time zones, you might miss something cool and want to catch up on it once you’re back online.

The problem was the usual one with algorithmic features, namely, lack of user control. Twitter gave users no control over the process: the "While you were away" thing would appear whenever it cared to, or not at all. There was no way to come online and call it up as your first stop to see what you had missed; you just had to scroll and hope it might show up. And then they just quietly dropped the whole feature.

Sideshow X

Twitter then managed to step on the exact same rake again when they rolled out a fully-algorithmic timeline, but, in response to vociferous protests from users, grudgingly gave the option of switching back to the old-style purely chronological one. Initially, it was possible to have the two timelines (algorithmic and chronological) in side-by-side tabs, but, apparently out of fear that the tabbed interface might confuse users, Twitter quickly removed this option and forced users to choose between either a purely chronological feed or one managed by a black-box algorithm with no user configurability or even visibility. Of course power users who used lists were already very familiar with tabs in the Twitter interface, but this was not a factor In Twitter’s decision-making.

To be clear, this dilemma between serving newbies and power users is of course not new nor unique to Twitter. This particular variation of it is new, though. Should social networks focus on supporting power users who want to manage their social graph and the content of their feed themselves — or should they chase growth by using algorithms to make it as easy as possible for new users to find something fun enough to keep them coming back?

There is also one factor exacerbating the dilemma that is somewhat unique to Twitter. Before That Guy came in and bought the whole thing, Twitter had been consistently failing to live up to an IPO valuation that was predicated on them achieving Facebook levels of growth. Instead, user growth had pretty much stalled out, and advertisers looking for direct-action results were also not finding success on Twitter in the same way as they did on Facebook or Instagram. The desperation for growth was what drove Twitter to over-commit to the algorithmic timeline, in the hope of being able to imitate TikTok’s growth trajectory.

There is irony in the fact that an undersung Twitter success story saw them play what is normally more a Facebook sort of move, successfully ripping off the buzzy new entrant Clubhouse with their own Twitter Spaces feature and then simply waiting for the attention of the Net to move on. Now, if you want to do real-time audio, Twitter Spaces is where it’s at — and they achieved that status largely because of Clubhouse’s ballistic trajectory from Next Big Thing to Yesterday’s News, with the rapidity of the ascent ruthlessly mirrored by the suddenness of the descent.

A more competently managed company — well, they wouldn’t have been bought by That Guy, first of all, but also they might have learned something from that lesson, held firm to their trajectory, and remained the one place where everything happened, and where everything that happened was discussed.

Instead, we have somehow wound up in a situation where LinkedIn is the coolest actually social network out there. Well done, everyone, no notes.

🖼️ Photos by Nastya Dulhiier and Anne Nygård on Unsplash