The Problem With Self-Driving Cars – And Self-Flying Planes

Many petrolheads are worried that self-driving cars will kill the idea itself of the car. Personally, I’m not that worried about that; horses have not been a primary means of transport for maybe a century, and yet there still seem to be plenty of enthusiasts who enjoy them. I rode my bike side-by-side with a horse just last weekend.

No, my main concern is about the process of getting to fully self-driving cars. Today, we have cars with all sorts of safety features such as radar cruise control and lane-departure warnings. These already add up to a limited self-driving capability – level 2 or perhaps even 3 in the NHTSA definition. I have used some of this functionality myself on the German Autobahn, with my hired Volvo staying in its lane, following curves in the road, and accelerating or braking with the traffic, including coming to a complete stop.

I was never able to get out a book or just climb into the back seat for a nap, though. I always had to remain alert and engaged in case of any failure of the self-driving systems. Ultimately, I found this more wearing than just driving myself, and so I disengaged all the systems, got off the clogged-up Autobahn, and found myself a twisty and more engaging alternative route where I could concentrate fully on the driving.

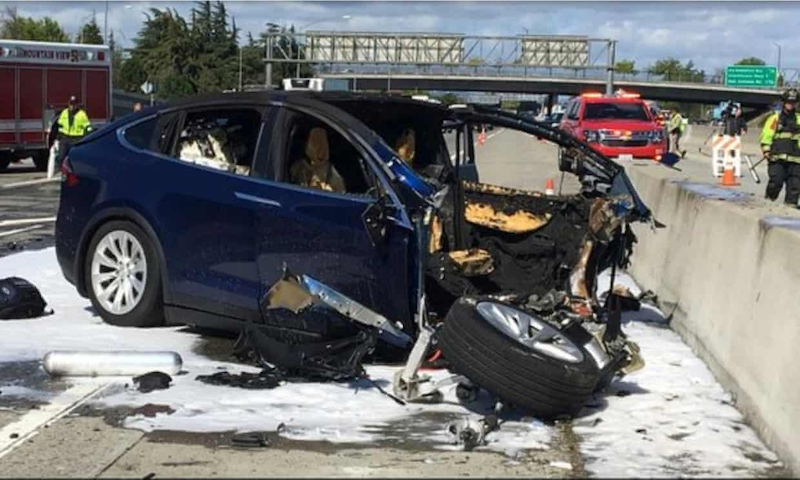

This is the "uncanny valley" problem of self-driving cars: in order to get to full autonomy, we have to deal with a transition period where the automated systems are not yet good enough to do the job, but they are already good enough for drivers to become distracted and disengaged from the process of driving. The risk is that when the systems fail, the driver is not able to re-establish situational awareness and take control quickly enough to avoid an incident. We saw this scenario play out with tragic consequences when a self-driving Uber car struck and killed a woman earlier this year.

This problem of operator attention is of course not unique to cars, and may in fact have played a part in the tragic Lion Air crash in Indonesia. As part of the investigation of that crash, it was uncovered that a faulty air-speed sensor may have been the proximate cause of the accident, leading to the plane’s avionics mis-identifying the situation as a stall and putting the nose of the plane down to recover the speed necessary to get out of that stall.

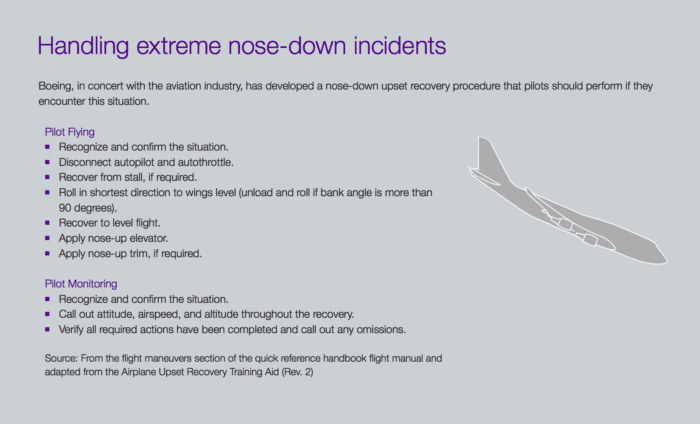

The FAA has now issued a directive to operators of the plane to update their manuals. The linked article includes this image, purportedly from an internal Boeing magazine, describing the steps involved in identifying and correcting this situation:

You’re a pilot, climbing on autopilot on a routine departure – so you don’t have much airspeed or altitude to play with. Suddenly for no apparent reason the plane pitches nose-down. You have to diagnose the problem correctly, disengage a bunch of systems, and recover manual control. It’s a hard task, even for trained aircraft pilots.

Now imagine the same situation in a self-driving car. You’re on the phone, thinking about something else, and suddenly the car is drifting across lane markings, straight towards a concrete highway divider.

How do you rate your chances?

It is true that these systems will only improve with real-world usage and with more data to learn from, but their marketing and usage need to be aligned to their actual capabilities and failure modes, not what we wish they would be or what they might be in ideal conditions. New interface paradigms may also be required to set operators’ experience accordingly.

Until we get there, a sensible minimum standard seems to be that we should not expect drivers to do anything as a matter of course that is difficult even for trained airline pilots.