This is not a breaking-news blog. Instead, what I try to do here is bring together different strands of thinking about an issue – hence the name: Find The Thread.

This is why I’m going to comment on the tragic story of the woman struck and killed by a "self-driving" Uber car in Arizona, even though the collision occurred more than a week ago.

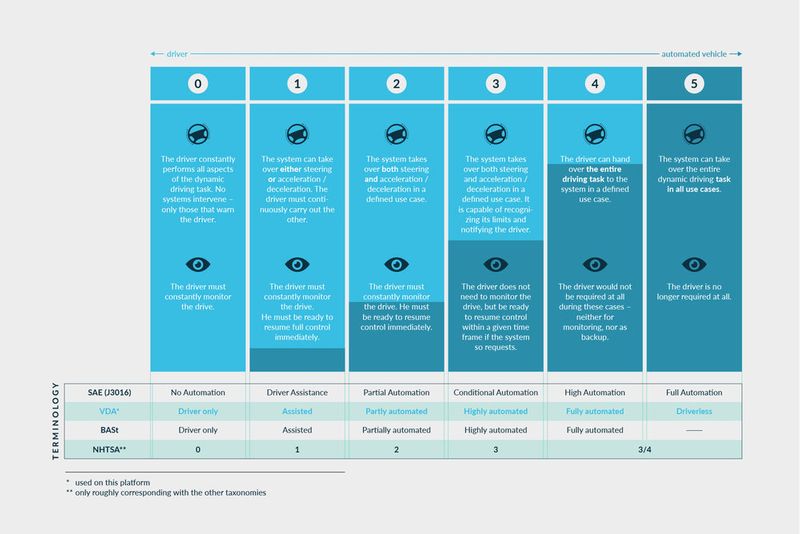

A Question Of Levels

We generally talk about levels of autonomy in driverless cars. Level 0 is the sort of car most of us are used to. Particularly high-tech cars – your Mercedes S-classes, Audi A8s, many Volvos, and so on – may have Level 1 or even 2 systems: radar cruise control that will decelerate to avoid obstacles, lane-keeping technology that will steer between the white lines on a motorway, and so on. Tesla also attempts Level 3 with its Autopilot tech.

In all of these cases, the driver is required to still be present and alert, ready to take over the driving at a moment’s notice. The goal is to get to Level 4 and 5, which is where the driver can actually let go of the wheel entirely. Once Level 5 is commonplace, we will start seeing cars built without manual controls, as they will no longer be required.

The problem, as Benedict Evans points out, is that this will not be a universal roll-out. As I have written myself, autonomous driving technology is likely to be rolled out gradually, with easy use cases such as highway driving coming first.

This is the nut of the issue, though: as long as human drivers are required as backup to self-driving tech that works most of the time, we are actually worse off than if we did not have this tech at all.

In the first known fatal accident involving self-driving tech, the driver may have ignored up to seven warnings to put his hands back on the wheel. That was an extreme case, with rumours that the driver may even have been watching a film on a laptop, but in the Arizona case, the driver may have had only between four and one seconds of warning. If you’re texting or even carrying on a conversation with other occupants of the car, four seconds to context-switch back to driving and re-acquire situational awareness is not a lot. One second? Forget it.

In tech circles, self-driving tech is mostly analysed as a technology problem. Can we do this with cameras and smarter processing, do we need expensive Lidar rigs, who has the smartest approach, and so on. This is all cutting-edge stuff, to be sure, and well worth investigating anyway. You can then start speculating about the consequences if this tech all works out, and I’ve had a go at thinking about what truly self-driving cars may imply myself.

Beyond The Software

There is a whole other level beyond the technological one, which is the real-world frameworks in which these technologies would have to operate. The sorts of driving licenses we issue to humans already focus more on the rules of the road than the techniques of driving. You can learn the mechanics of driving in a few hours, especially with an automatic gearbox. The reason we don’t give people licenses after a day of instruction is that we also require them to understand how to drive on public roads shared with others.

This tragic accident in Arizona has shifted the conversation to whether it is possible to sue an autonomous car. I am working with some major automotive manufacturers, and all are developing self-driving tech – but none are prepared to roll it out, or even discuss it much in public, until these aspects have been sorted out. Car-makers are a fairly conservative bunch, used to strict product liability laws.

In contrast, the software industry by and large accepts the idea that a click-through waiver absolves you of all responsibility for your products. That is not at all how the automobile industry operates. Even strictly software faults are held to a level of scrutiny unknown in the general software industry, outside of specialised applications. In the case of Toyota’s unintended acceleration problems, the car-maker was ultimately held responsible in court for a fatal accident, due to identified bugs in its electronic throttle control system – and to the fact that code metrics indicated the probability that other, as-yet unidentified bugs were still present in the codebase for that system.

Jamie Zawinski has some typically acerbic commentary:

Note that the article's headline referred to the woman killed by the robot as a "pedestrian" instead of a person. "Pedestrian" is a propaganda term invented by the auto industry to re-frame the debate: to get you to preemptively agree that roads, and by extension cities, are for cars, and any non-car-based use is "other", is some kind of special-case interloper. See The Invention of Jaywalking.

Semantics aside, I have one question that I think is pretty important here, and that is, who is getting charged with vehicular homicide? Even if they are ultimately ruled to be not at fault, what name goes on the court docket? Is it:

The Uber employee - or "non-employee independent contractor" - in the passenger seat?

Their shift lead?

Travis Kalanick?

The author(s) of the (proprietary, un-auditable) software?

The "corporate person" known as Uber?

Good question, and one that so far remains unanswered.

Why The Rush To Autonomous Cars?

Finally, let’s remember that there are two reasons that the industry is storming ahead with self-driving tech. The public reason is the presumption of increased road safety through the removal of distracted human drivers from the road. However, as the complexities involved in moving beyond simple demos in an empty parking lot become clear, people are starting to suggest ridiculous solutions like "bicycle-to-vehicle" communications – in other words, instrumenting cyclists so that they will advertise their position to cars. And if you give sensors to cyclists, why not pedestrians too?

This is a typical technology-first fix: if you can’t solve the problem one way, by detecting cyclists through sensors, you solve it another way, by fitting sensors to the cyclists themselves. Here again, though, we are not in a purely technological domain. This blinkered view is why self-driving cars won’t save cyclists, at least until the thinking shifts around the whole issue of cars in general.

Here is where we come to the second reason behind the urgency in the development of self-driving tech: Uber’s business model depends on it. Right now they are haemorrhaging money – over a billion-with-a-B per quarter in 2017 – in a race to achieve market dominance before they run out of cash (or investors willing to give them more). Much of that cost goes to their human drivers; if those could be replaced with automated systems, the cost would go away at a stroke, and they would also achieve much higher utilisation rates on their fleet of vehicles.

In this view, self-driving cars are both an offensive move against Uber’s competitors, and a defensive one in case the likes of Google get there first and undercut Uber with their little pod-cars.

This sort of thing is catnip for futurists and other professional speculators, existing at the nexus of technology and business model that is Silicon Valley distilled to its purest essence. However, as the real-world problems with this project become more and more visible, people are starting to question whether self-driving cars are actually a distraction for Uber.

The bottom line is that right now we are pushing forwards with self-driving tech in the hope it will make our roads safer. This is a valid and important goal, to be sure – but those claims of increased safety from self-driving tech are still assumptions, very much unproven, as the tragic death in Arizona reminds us.

Along the way to full Level 5 autonomy, we must pass through an "uncanny valley" of partial autonomy, which is actually more dangerous than no autonomy at all.

Adding the desperate urgency of a company whose very survival depends on the success of this research seems like a very bad idea on the surface of it. It is all too easy to imagine Uber (or any other company, but right now it’s Uber), with only a quarter or two worth of cash in the bank, deciding to rush out self-driving tech that is 1.0 at best.

It’s said that you shouldn’t buy any 1.0 product unless you are willing to tolerate significant imperfections. Would you ride in a car operated by software with significant imperfections?

Would you cross the street in front of one?

And shouldn’t you have the choice to make that call? This is why, despite claims that the EU’s strategy on AI is a failure, I like their go-slow approach. Sure, roll out 1.0 animoji or cat-ear filters, but before we rely on computer vision not to run people over, or fine them for jaywalking or whatever, we should maybe stop and think about that for a moment.