From Provincial Italy To London — And Back Again

More reflections on remote work

Well, I'm back to travelling, and in a pretty big way — as in, I'm already to the point of having to back out of one trip because I was getting overloaded! I've been on the road for the past couple of weeks, in London and New York, and in fact I will be back in New York in a month.

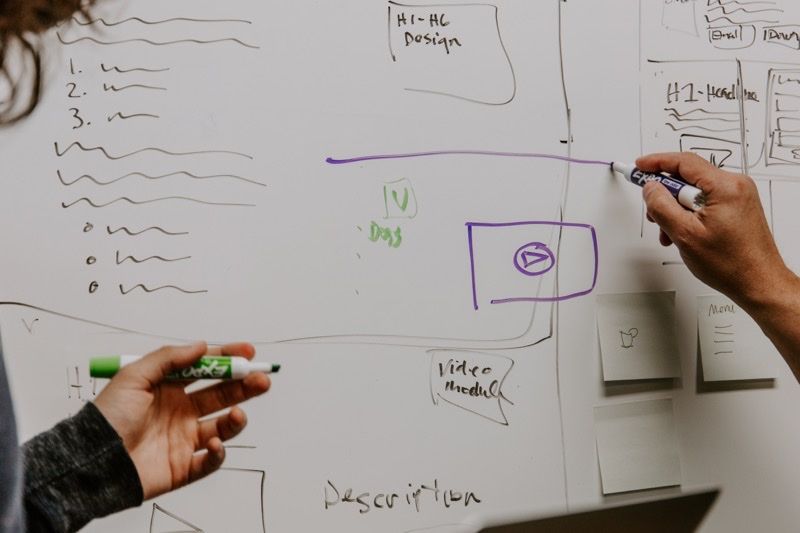

It has honestly been great to see people, and so productive too. Even though I was mostly meeting the same people I speak to week in, week out via Zoom, it was different to all be in the same room together. This was also the first time I was able to get my whole team together since its inception: I hired everyone remotely, and while I have managed to meet up with each of them individually, none of the people on the team had actually met each other in person… We had an amazingly productive whiteboarding session, where we knocked out some planning in a couple of hours that might otherwise have taken weeks, and probably justified a chunk of the cost of the trip on its own.

This mechanism also showed up in an interesting study in Nature, entitled Virtual communication curbs creative idea generation. The study shows that remote meetings are better for some things and worse for others. Basically, if the meeting has a fixed agenda and clear outcomes, a remote meeting is a more efficient way of banging through those items. However, when it comes to ideation and creativity, in-person meetings are better than remote ones.

As with all the best studies, this result tallies with my experience and reinforces my prejudices. I have been remote for a long time, way before the recent unpleasantness, but I always combined remote work with regular in-person catch-up meetings. You do the ideation and planning when you can all gather together around the whiteboard — not to mention reinforcing personal ties by gathering around a table in a restaurant or a bar! Then that planning and those personal ties take you through the rest of the quarter, with regular check-ins for tactical day-to-day actions to implement the strategic goals decided at the in-person meeting.

Leaving London

Something else that was interesting about my recent trips was meeting a whole lot of people who were curious about my living situation in Italy — how I came to be there, and what it was like to work a global role from provincial Italy, rather than from one of the usual global nerve centres. Telling the story in New York, coming fresh from my trip to London, led me to reflect back on how come I left London and whether it was the right call (spoiler: it totally was).

The London connection also showed up in a pair of articles by Marie Le Conte, who recently spent a couple of months in Venice before returning to London. It has been long enough since I left London that I no longer worry about whether prices in my favourite haunts will be different, but whether any of them are still there or still recognisable — and sadly, most of them are not. But then again, this is London we are talking about, so I have new favourites, and find a new one almost every trip.

Leaving London was a wrench: it was the first place I lived after university, and I enjoyed it to the hilt. Of course I had to share a flat, and I drove ancient unreliable cars1. But we were out and about all the time, in bars and theatres, eating out and meeting up and just enjoying the place.

However, over the following years most of my London friends moved away in turn, either leaving the UK outright or moving out to the commuter belt. The latter choice never quite made sense to me: why live somewhere nearly as expensive as London (especially when you factor in the cost of that commute), which offers none of the benefits of being in actual London, and still has awful traffic and so on? But as my friends started to settle down and want to raise families and so on, they could no longer afford London prices. Those prices get especially hard to justify once you could no longer balance them out by enjoying everything London has to offer — because you're at home with the kids, who also need to be near a decent school, and get back and forth from sports and activities, and so on and so forth.

My friends and I experienced the same London in our twenties that Marie Le Conte did: it didn't matter if you "rent half a shoebox in a block of flats where nothing really worked", because "there was always something to do". But if you're not out doing all the things, and you need more than half a shoebox to put kids in, London requires a serious financial commitment for not much return.

But why commute to the office at all?

Even before the pandemic, remote work allowed many of us to square that circle. We could live in places that were congenial to us, way outside commuting range of any office we might nominally be attached to, but travel regularly for those all-important ideation sessions that guided and drove the regular day-to-day work.

The pandemic has opened the eyes of many more people and companies to the possibilities of remote work. Airbnb notably committed to a full remote-work approach, which of course makes particular sense to Airbnb, expecially the bit about "flexibility to live and work in 170 countries for up to 90 days a year in each location". I admit they are an extreme case, but other companies have an opportunity to implement the parts of that model that make sense for them.

Certain functions benefit from being in the office all the time, so they require permanent space. This means both individual desks and meeting rooms. Meanwhile, remote workers will need to come in regularly, but when they do, they will have different needs. They will absolutely require meeting rooms, and large, well-equipped ones at that, and those are on top of whatever the baseline needs are for the in-office teams. On the other hand, the out-of-towners will spend most of their time in meetings (or, frankly, out socialising), and so they do not need huge numbers of hot desks — just a few for catching up with emails in gaps between meetings.

If you rotate the in-office meetings so you don't have the place bursting at the seams one week and empty the rest of the time, this starts to look like a rather different office setup than what most companies have now. You can even start thinking of cloud-computing analogies, no longer provisioning office space for peak utilisation, but instead spreading work to take advantage of unused capacity, and maybe bursting by renting external capacity as needed (WeWork2 et al).

If you go further down the Airbnb route and go fully remote, you might even start thinking more about where you put that office. Does it need to be in a downtown office core, or can it be in a more fun part of town — or in a different city entirely? Maybe it can even be in a resort-type location, as long as it has good transport links. Hey, a guy can dream…

But in the mean time, remote work unlocks the ability for many more people to make better choices about where to live. Raising a family is hard enough; doing it when both parents work is basically impossible without a strong local support network. Maybe the model should be something like the Amish Rumspringa, where young Amish go spend time out in the world before going back home and committing to the Amish way of life. Enjoy your twenties in the big city, get started on your career with the sort of hands-on guidance that is hard to get remotely, and then move back home near parents and friends when it's time to settle down, switching to remote working models — with careful scheduling to avoid both parents being away at once.

Once you start looking at it like that, provincial Italy is hard to beat. Quality of life is top-notch, with the sort of lifestyle that would require an extra zero on the salary in London or NYC. If you combine that with regular visits to the big cities, it's honestly pretty great.

🖼️ Photos by Kaleidico and Jason Goodman on Unsplash; London photograph author’s own (the view from my hotel room on my most recent London trip).

-

I only had a car in the first place because I commuted out of London, to a place not well-served by trains; I never drove into central London if I could avoid it, even before the congestion charge was introduced. ↩

-

Just because WeWork is a terrible company doesn't mean that the fundamental idea is wrong. See also Uber: while Uber-the-company is obviously unsustainable and has a number of terrible side-effects, it has forced into existence a ride-hailing market that almost certainly would not exist absent Uber. Free Now gives me an Uber-like experience (summon a car from my phone in most cities, pay with a stored card), but using regular licensed taxis and without the horrible exploitative Uber model. ↩