Things That Happen When You're Working From Home

So this is me, talking to dozens of colleagues about a new project — when my daughter, I mean my coworker, decided she needed something off my desk Right Now.

My colleagues all thought she was cute, so there’s that.

Working From Home Is Good, Actually

It’s an obvious time for people to think and write about working from home. I did my own bit yesterday, and today Kevin Roose joined in with this article in the New York Times, with the clickbaity title "Sorry, but Working From Home Is Overrated".

Mr Roose used to be a fan:

I was a remote worker for two years a while back. For most of that time, I was a work-from-home evangelist who told everyone within earshot about the benefits of avoiding the office. No commute! No distracting co-workers! Home-cooked lunch! What’s not to love?

But he changed his tune:

I’ve now come to a very different conclusion: Most people should work in an office, or near other people, and avoid solitary work-from-home arrangements whenever possible.

What drove this change of heart?

[…] research also shows that what remote workers gain in productivity, they often miss in harder-to-measure benefits like creativity and innovative thinking. Studies have found that people working together in the same room tend to solve problems more quickly than remote collaborators, and that team cohesion suffersin remote work arrangements.

I don’t disagree! I’ve worked from home for fifteen years, but I’ve always spent big chunks of my time on the road, travelling and meeting people. Working in a distributed team, it’s key to meet in person on a regular basis, at least once a quarter. If I don’t leave my home office for a couple of weeks straight, I start to get cranky – so while I’m more prepared than most for remote working, not least because I have a home office that is fully set up, with big screen, ergonomic keyboard, and even a whiteboard, I am still affected by the coronavirus lockdown.

As #COVID19 turns us into homebodies, the introvert vs extrovert battle rears its head. I am both. I sleep late, sneak out of parties, see movies alone, but I also work remotely from food courts, need to be outside daily, and get energy from humans. Per @jina, I’m an “ambivert!”

— Scott Hanselman 🌮 (@shanselman) March 11, 2020

As with most things, the answer is not a simple binary:

[…] research has found that the ideal amount of work-from-home time is one and a half days per week — enough to participate in office culture, with some time reserved for deep, focused work.

Around The World

There is one more factor that I don’t often see considered, and it’s geographical coverage. I am part of a global team, and one of the things that I bring to the team is the perspective of someone who is not based in New York City or in Silicon Valley. If the whole global team sat around a long table, they would miss important perspectives and developments on the ground. But if all of us are dotted around the world, why would we go in to our various local offices? There, we would indeed sit at long tables, but with people working on very different projects. Distraction and disturbance are rife in that sort of environment (I speak from experience here).

It can still be worth taking that hit on deep work occasionally for the serendipitous conversations with other teams which can occur in that type of environment, but there’s not the same benefit to doing it long-term. The way I do it is to stop in at the local office wherever I am and sit with different teams in rotation, working to facilitate serendipity in different circumstances. That way I can take the temperature of the extended organisation and report back to the team, sharing perspectives with others who are doing the same thing.

There are also things that can be done to help cohesion of remote teams. The NYT article mentions "virtual coffee breaks", which I haven’t tried, but simple things like holding regular calls and turning on webcams during them will go a long way. Floating Slack conversations about non-work topics are also good – again, especially if they are a way to maintain bonds that are built in person and regularly strengthened that way.

Bottom line, it does not seem like the right time to be negative about remote work, right when many people and organisations are trying it for the first time. By all means warn them of pitfalls, but suggest fixes rather than just writing off the whole thing.

🖼️ Photos by Jacky Chiu and Helloquence on Unsplash

Tecniche di Sopravvivenza al Lavoro da Casa

Suggerimenti da uno che non va in ufficio da quindici anni

Oggi come oggi, la maggior parte di noi lavora nel famigerato "settore terziario", e quindi tipicamente in ufficio. In Europa come negli Stati Uniti, il settore dei servizi rappresenta circa 80% del PIL. Questa crescita del lavoro in ufficio è un fenomeno relativamente recente; fino a pochi decenni fa, la maggior parte della gente lavorava nell’agricoltura

Il lavoro in ufficio porta tutta una serie di vantaggi rispetto al lavoro nei campi. Tanto per cominciare, si sta al chiuso, seduti, in ambienti abbastanza confortevoli. Magari c’è anche la possibilità di bere un caffè o qualche altra bibita, ed i più fortunati hanno anche qualche collega simpatico con cui chiacchierare. Raramente c’è pericolo di farsi seriamente male, a condizione di stare attenti con le graffette.

Il problema è che i protocolli d’isolamento istituiti dal governo ci obbligano a lavorare da casa invece di andare in ufficio. In Italia in particolare molte persone e molte società si trovano per la prima volta a fronteggiare questa situazione. Per dare una piccola mano, volevo condividere alcune indicazioni basate sulla mia esperienza. Per trovare l’ultima volta in cui lavoravo nello stesso ufficio con i miei colleghi, dobbiamo andare a risalire al 2006. Da allora, ho sempre lavorato in team distribuiti, con capi e colleghi sparsi in vari paesi e fusi orari.

Ecco che cosa ho imparato.

Prenditi il tuo spazio

Una lato positivo del trasferirsi fisicamente da un’altra parte per lavorare è la separazione che si crea fra lavoro e non-lavoro. Se sei in ufficio, stai mediamente lavorando, pause caffè a parte – e se sei a casa, tipicamente non stai lavorando, a parte qualche occhiatina alla mail di straforo.

Quando lavori da casa, questa separazione si perde. Il rischio è che il lavoro ed il non-lavoro si confondano, portandoti a dimenticare di mangiare ed a lavorare fino a notte, oppure a distrarti continuamente con lavoretti e commissioni.

Dove possibile, la soluzione migliore è la separazione fisica. Non lavorare dal divano! Va bene per una mezz’oretta, ma se lo fai per giornate e settimane intere, la tua schiena vi maledirà – e ricordati che adesso come adesso non puoi neanche andare a fare fisioterapia… Trovati un posto specifico dove lavorare, e non andarci quando non stai lavorando. Io sono abbastanza fortunato da avere una tavernetta in cui ho allestito il mio ufficio, ma non tutti avranno questa possibilità. Se però lavori ad esempio al tavolo della cucina, quando hai finito chiudi il computer e spostati dal tavolo.

Può sembrare una cosa piccola, ma cerca di rispettare al massimo gli orari ed anche il vestiario da ufficio. Hai anni e anni di riflessi che ti ricordano inconsciamente che quando ti radi o ti trucchi, stai incominciando la giornata lavorativa. Continua ad utilizzare questi riflessi anche se non esci di casa.

Se ne hai la possibilità, prendi in considerazione anche una corsetta o un giro in bici nel tempo che altrimenti avresti passato da pendolare in macchina o in treno.

Proteggi i tuoi spazi

Se vivi con altre persone, sarà necessario negoziare questa separazione anche con loro. Se ti vedono in casa, avranno naturalmente l’istinto di chiederti una mano o di fare una chiacchiera. Cerca di istituire un segnale anche fisico: se la porta della cucina è chiusa, sto facendo un lavoro di concetto oppure sono al telefono con i colleghi, per cui non sono disponibile. Se la porta è aperta, posso fare una pausa caffè.

Costruisci una routine

Oltre all’organizzazione degli spazi, è importante anche quella dei tempi. Dividi la giornata in unità di tempo, ed assegna ciascuna unità ad un compito specifico. Io personalmente mi trovo bene con la tecnica del pomodoro, semplice e divertente. Fondamentalmente si tratta di utilizzare un timer da cucina per tracciare le attività ed i tempi necessari.

Il mio timer Pomodoro timer personale sulla scrivania

Comunicare, comunicare, comunicare

Lavorare a casa da soli può essere molto isolante, soprattutto per chi è abituato a lavorare a stretto contatto con i colleghi. Almeno finché siamo tutti isolati a casa propria, non sentiamo il pericolo di trovarci esclusi da conversazioni che avvengono in ufficio. Esistono vari modi per fare sì che il team rimanga tale anche senza vedersi di persona per qualche settimana o mese.

La base è una piattaforma di chat sera. Slack è una delle soluzioni più diffuse, con un livello gratis che è più che sufficiente per piccole realtà o per cominciare con questo strumento. L’alternativa più diffusa probabilmente è Microsoft Teams, ma ce ne sono molte altre.

Non cercare di usare WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger, o simili per questo scopo. Per cominciare non hanno la nozione dei "canali", per cui tutte le conversazioni avvengono nei gruppi, né client desktop, né funzionalità serie di ricerca – tutte cose necessarie per poter lavorare.

L’altro motivo per lavorare con uno strumento dedicato al lavoro è per mantenere la separazione fra lavoro e non-lavoro. Se succede tutto nella stessa app, farai molta più fatica a distinguere i due mondi. Soprattutto se sei un manager, evita di utilizzare questi canali se non in situazioni di emergenza.

Troviamoci in video

La chat testuale è uno strumento fantastico, ma se ti senti solo ed isolato dai colleghi, accendi quella webcam! Siamo animali sociali, e vedere in faccia la gente aiuta a rinforzare i legami sociali. La crisi attuale sta portando ad un aumento enorme dell’adozione di strumenti di video conferenza, in particolare Zoom, che ha un’opzione gratis per video chiamate fino a quaranta minuti.

Un altro vantaggio delle video conferenze è che ti costringe a vestirti da persona seria invece di passare la giornata in pigiama e vestaglia, sempre per la questione della separazione casa/lavoro e dei relativi riflessi.

Traccia quello che fai

Infine, può darsi che tu faccia fatica a tirare le somme alla fine della giornata, e che tu ti senta di non aver concluso niente. La soluzione più semplice è di scriverti dei piccoli appunti durante la giornata, ad esempio come commenti agli intervalli di Pomodoro. Se fai un lavoro per il quale è necessaria questa tracciabilità, magari hai già strumenti più specializzati, ma anche se non hai queste esigenze, psicologicamente fa bene tirare le somme alla fine della giornata con dei risultati concreti.

Pianifica per il futuro

È importante pensare adesso a come lavorare da casa perché è estremamente probabilmente che molte persone ed aziende decidano di continuare con questa modalità di lavoro anche una volta rientrata la crisi. Il lavoro remoto ha enormi potenzialità, almeno come complemento occasionale al lavoro in ufficio. Cerca di non prendere brutte abitudini adesso; pensa al lungo termine, non solo alla giornata o alla settimana.

Se hai altri suggerimenti o commenti, di solito mi puoi trovare su Twitter.

🖼️ Foto di Dillon Shook, Harry Cunningham e Andrew Neel via Unsplash, trance il timer a pomodoro che è il mio.

How to Survive the Home Office

Some tips from someone who hasn’t worked in an office in fifteen years

In the twenty-first century, many of us work in offices. In the EU and the US, the service economy represents roughly 80% of GDP. This growth of service work is a relatively recent phenomenon, compared to the past when most employment was in agriculture.

Office work comes with a number of perks over farming. For a start, it’s done indoors, generally in fairly comfortable surroundings. There may be perks like free refreshments, and if you are lucky you may even have fun colleagues that you like to hang out with during coffee breaks. You’re also fairly unlikely to be in any sort of physical danger, as long as you are careful with the stapler.

The problem is that the self-isolation protocols that governments and companies are putting into place require, among other things, that people work from home instead of going to the office. This is a new development for many employers and employees. In the spirit of helping out, I wanted to share some tips based on over a decade of working from home. I last had an office-based job in which I worked elbow-to-elbow with my team-mates in 2006. Since then, my situation has mostly involved team-mates and managers spread around the world, across many different time zones. Here is what I learned.

Day 1 of working from home:

— James Felton (@JimMFelton) March 6, 2020

I might make myself some nice food as a treat.

Day 5:

Forgot to shower again, but that's not a problem for I no-longer wear people clothes. Lunch was sweetcorn I scooped up with a biscuit. At breaktime, I snarled at the locals from behind my bins.

Save your Space

One of the good things about travelling to a physical location is that it enforces separation between work and not-work. If you’re in the office, you’re generally expected to be working – and if you’re at home, generally speaking you’re not working, apart from perhaps checking email or whatever.

When you work from home, you lose that separation. The risk then is that work and home life bleed into each other. On the one hand, you may find yourself working through meal times and into the evening, but on the other you might also get distracted by housework or errands.

If you can arrange it, physical separation is best. Don’t work from the couch; apart from anything else, that’s an ergonomic nightmare if you’re doing it all day, every day. Go somewhere to do work, and don’t go there when you’re not working. I’m lucky enough to have a home office that is physically separate from the family home, which is ideal, but not everyone will have that option, or be able to set it up at short notice.

At the very least, work from your laptop at the table, and close the laptop when you’re done. Even if you do dip into work after hours, do it from your phone, not from the laptop.

It might seem silly, but try to stick to office hours and dress: get out of bed and get dressed as if you were going to work. You have years of reflex telling you that when you shave or put on makeup (delete as appropriate to your own personal morning routine), you are going into "work mode". Take advantage of those reflexes even if you aren’t leaving the home.

If you are able to do so safely, i.e. without close contact with others, you may also consider replacing your commute with a run or a bicycle ride, just to start your day off.

Protect your Space

If you live with other people, you may need to negotiate this separation with them. If they see you in the house, they may ask you for your help, or to join in some activity, or just ask you questions. A physical indicator that you are working can be useful here. Again, if you have a specific location that you work from, that can be simplest: "if I’m in the spare room with the door closed, please don’t bother me; if the door is open, I’m available for coffee or a quick chat".

Make your Routine

On top of physical routine, it’s good to break up your day into units of time, and dedicate each one to a specific task. The method I use is the Pomodoro Technique, which is simple and fun. Basically, get a kitchen timer, and use it to time your tasks and breaks.

My Pomodoro timer on my desk

Over-Communicate

It can be very isolating to work at home on your own, if you are used to working cheek-by-jowl with your team. At least if everyone is self-isolating in their own homes, you don’t feel that you are being left out of impromptu conversations that happen in the office. There are ways of helping the team continue to feel and work like a team even when they are remote.

The absolute bottom line is that you need a chat platform of some sort. Slack is fast becoming the default, and has a free plan that is enough for most organisations at least to get started. Probably the biggest alternative is Microsoft Teams, but there are many other options.

Do not try to use WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger, or similar mobile-only, single-threaded tools for anything beyond the smallest groups and simplest needs. Slack and similar tools allow you to create many channels, each dedicated to specific topics, and within a channel you can split a discussion off into a thread without cluttering up the main channel.

Another benefit of dedicated work chat tools is to further that separation between work and personal time. Train yourself to stop looking at the work tool after hours. Managers, be sensitive and avoid abusing personal channels like SMS outside of actual emergencies.

Catch my Video

Text chat is great for many things, but if you’re feeling lonely and isolated away from your team, turn on that webcam! We are social animals, and seeing people face to face really helps strengthen those team bonds. The coronavirus crisis is driving a huge uptake in video chat tools, especially Zoom, which has a useful free tier.

Another benefit of video meetings is that it reinforces your work routines, if only because you have to be presentable and ready to be seen on camera.

Track and Assess

Finally, it can be hard at the end of the day to work out whether you "got anything done". There’s a simple fix for that too: track what you do during the day, and assess the results at the end of the day. You can do this as part of your Pomodoro Technique, jotting down a quick note about what you achieved during each Pomodoro interval. Depending on what type of work you are doing, this can also help you track your time, if that is a requirement. Even if you don’t have that kind of need, though, it can be good to close out the day by looking back on what you have achieved.

Plan for the Long Term

The final reason to think about this topic now is that I suspect that many organisations that were only forced into supporting remote work by this crisis will find that it’s actually a great option, at least as a complement to their ordinary setup. Don’t fall into any bad habits because you think this setup will only last for a few days or weeks. Remote working is going to be much more prevalent in the future, so it’s worth getting it right straight away.

Do share any other tips that you personally know of or that work for you. I can usually be found on Twitter.

🖼️ Photos by Dillon Shook, Harry Cunningham and Andrew Neel on Unsplash, except tomato timer – author’s own

Ominous clouds above the pass

Hello there

Sun peeking through snow clouds at Les 2 Alpes. This was taken with my iPhone 11 Pro, and I’m just amazed at what it was able to do with the light and the snowflakes.

Note taking

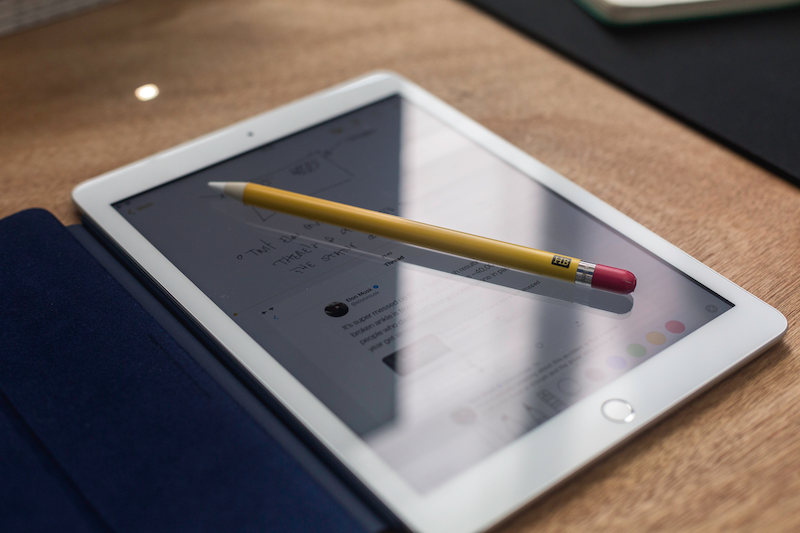

It’s been ten years since the launch of the iPad, so it seems appropriate to reflect back on what effect it has had. The two best retrospectives that I’ve read are by Federico Viticci and Steven Sinofsky.

Personally, I’ve owned three iPads; the original squared-off one was more a proof-of-concept than a fully-fledged device, but I loved it to bits, and hung onto it until the first Retina iPad came out. Again, that was perhaps an early release and was quickly superseded, but I hung onto it until the Pro 10,5 tempted me with its keyboard cover and Pencil. Now I’m just waiting for the current Pro to be refreshed, especially as my keyboard cover appears to have died.

The input devices, whether keyboard or stylus, are what I really wanted to talk about in this post. My work involves a fair amount of note-taking, whether in a meeting, during a presentation, or while brainstorming, on my own or in a group. I find the iPad to be the ideal device in all these situations, but before explaining why, I need to take a step back.

Many people will tell you that there are all sorts of cognitive benefits to taking notes using pen and paper as opposed to an electronic device. Most articles you will find online link back to this study published with the Association for Psychological Science. I don’t have access to the actual paper, but here’s the abstract:

Taking notes on laptops rather than in longhand is increasingly common. Many researchers have suggested that laptop note taking is less effective than longhand note taking for learning. Prior studies have primarily focused on students’ capacity for multitasking and distraction when using laptops. The present research suggests that even when laptops are used solely to take notes, they may still be impairing learning because their use results in shallower processing. In three studies, we found that students who took notes on laptops performed worse on conceptual questions than students who took notes longhand. We show that whereas taking more notes can be beneficial, laptop note takers’ tendency to transcribe lectures verbatim rather than processing information and reframing it in their own words is detrimental to learning.

I should admit up front that I fully agree with this study’s conclusions, based on my own empirical experience.

Laptops Are Not Good For Notes

The study examined students who took notes on laptops and compared them to students who took notes longhand. These two tools represent fundamentally different modes of thinking, and so it’s not surprising that the results are different. Laptops are linear, constraining users to interfaces that assume sequential text entry. They are great for editing, and for composition of certain types of content, but not great at enabling non-linear jumps and exceptions to structures. More complex options like mind-mapping software add cognitive load without guaranteed benefits. I certainly find I spend more time futzing with the map, especially when trying to follow someone else’s train of thought, than actually taking notes!

Distraction – and the Suspicion of Distraction

The study I mentioned above dismissed distraction as a concern, and certainly if you’re motivated, you’ll find ways to avoid distractions. I will note in passing that iPads are better than any laptop for avoiding distraction, simply because they default to showing a single app taking up the whole screen. Sure, you still get notifications, but those can be filtered out more easily than on a laptop. Almost equally important, though, is the perception of distraction on the part of onlookers. The open laptop screen creates a barrier between speaker and note-taker, where it’s usually not possible for the speaker to know whether their counterpart is distracted by something else.

I actually ran into this back in the day. In the early years of the century I was the only person I knew using a stylus-equipped smartphone, a Sony-Ericsson P800 (and later a P990), and I would sometimes also use them to take notes in meetings.

The handwriting recognition was actually pretty decent (although I’ve never used an Apple Newton to compare the two), so this system worked pretty well. The one drawback was that I would get funny looks from other people in the meeting, and in fact once a more senior colleague told me to "stop playing with the phone" and demanded to see the screen before he would believe I wasn’t playing a game or something!

Write and Forget

The reason I was going to the effort of taking notes using a fairly rigid handwriting recognition system on a small screen is that, while it required a bit of effort in the moment, it made my life easier after the meeting, when I could quickly send notes via email, copy them into a CRM (Siebel or Salesforce), and search them and collate them with other interactions in the past.

Doing that with notes on paper is kind of hard. Notes that start life in electronic form make it trivial.

Back to the iPad

The iPad is the perfect device for all of these reasons and more. Using the Pencil, I can take notes freeform, without worrying too much about context. I can circle things, draw arrows, insert diagrams, and even drop in a photograph I took of a speaker’s slide – and then write and draw on that.

By taking notes like this, I keep all the cognitive benefits of taking notes on paper, but all the notes I take can also be tagged and searched, so that I can easily refer back to them and link them together. An additional benefit is that it’s trivial to share those notes with others after the fact.

Finally, I can do all of this with the iPad flat on the table, without creating a barrier between me and someone I’m speaking to. If we’re face to face, we can even start sketching together, as we might have done in another age with the proverbial cocktail napkin.

The one thing that’s missing, in fact, is a collaborative version of this way of working. I’ve been in group meetings where we use a Google Doc as a combination of note taking and back-channel communications. This approach works best when there is one dedicated note-taker, who is advertised as such, so the speaker is comfortable with their constant typing. Other participants can then dip in and out as needed. It is possible to join in from an iPad, but it’s not ideal, and I would love something like a flexible shared canvas with textual notes pinned to it. Send me a beta code if you decided to build this, won’t you?

Good morning!

View of the Presolana massif at dawn

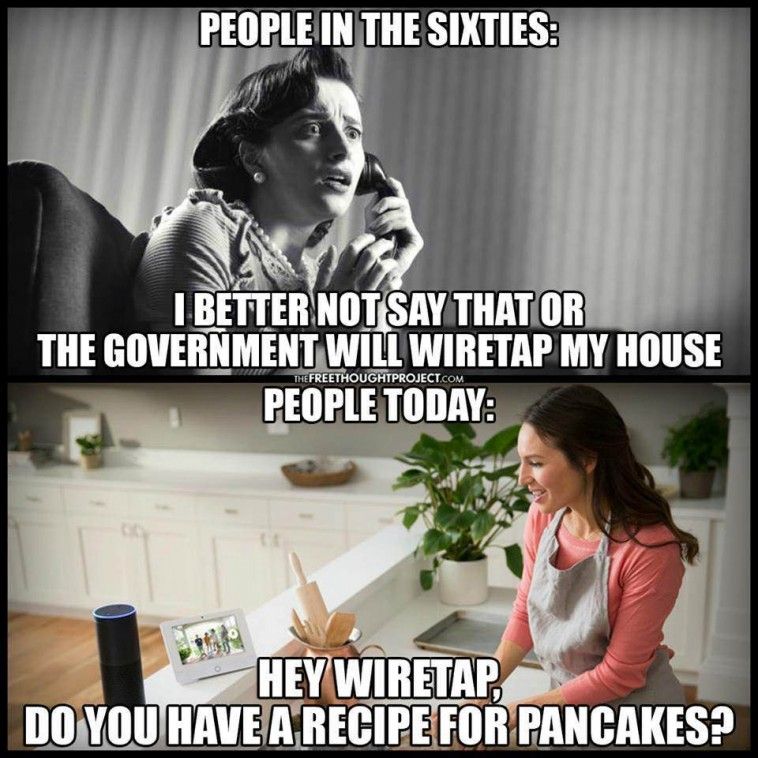

The Internet of Unwelcome Gifts

It’s that time of year when many of us are out buying gifts for ourselves or others – or if you’re tight like me, waiting for the sales in the New Year to buy those big-ticket items. Ahem. Regardless, please do not buy IoT / "smart" devices as gifts for people you care about.

Here’s the thing: at this point in time, most people who want a dedicated assistant-in-a-can device already have one. If they don’t own one already, it may be because they realise they will hardly use it – most of these things are only ever used to play music and maybe set a timer. The first many of us knew about Amazon’s efforts to sell Alexa skills for actual cash money was when they missed their revenue forecast… badly. How badly did they miss? Well, against what I would have thought was a pretty conservative target by Amazon’s standards of $5M, they achieved… $1.4M. That’s 28% attainment, also known in sales circles as "pack up your desk and get out – and be quick about it, I already called Security". In other words, very few people are using Skills at all, and basically none are using for-pay skills.

Of course there are any number of surreptitiously "smart" devices. For instance, these days it is pretty much impossible to buy a consumer TV without an operating system powerful enough to connect to the Internet over wifi and run streaming-video apps. This also means they are powerful enough to snoop on user’s behaviour. You might think this is not too bad – after all, YouTube already knows exactly which cute cat videos you watched – but these days, the state of the art is capturing whatever is displayed on screen, and trying to run analytics on that. If you watch home videos or display your photos, well, the privacy policy you clicked through when you set up the TV says it’s okay for the company to own those now. This is why even staid Consumer Reports is offering advice to turn off snooping features in smart TVs — and yes, they called it "snooping", not me.

If you think TVs are bad, other categories are even worse; see this IEEE report that calls out security risks of drones, vibrators, and children’s toys.

All of this means that there is a good chance that your possible gift recipient, especially if they are technically inclined, considered and rejected smart devices for security reasons. In case you think I’m just a lone crank over here in my tinfoil hat, it’s worth noting that the FBI issued notices about securing smart TVs around Black Friday, while the French government just sent out this warning about internet-connected food processor.

At least someone with some technical skills might have a chance of heading off the snooping at the network edge with something like a Pi-Hole. Definitely don’t buy anything with an Internet connection for your Muggle friends and relatives!

This is the sort of thing that Mozilla’s excellent Privacy Not Included project is designed to highlight. Note that this is not a blanket anti-tech position; if you browse over to the Privacy Not Included site, there are a ton of "smart" devices that are not creepy. But then there are the others, such as the infamous Ring camera, which manages a hat trick of terrible security, accommodation with a surveillance-driven police state, and enablement and reinforcement of racist tendencies.

In light of recent reports about the security of Ring devices, we’re suspending our recommendation of Ring products & updating affected guides as soon as possible. Ring owners should turn on 2FA & update their passwords with a new, previously unused one. https://t.co/96G6bSmxwq

— NYT Wirecutter (@wirecutter) December 19, 2019

In this context, Apple’s announcement that they are joining forces with Amazon, Google, and Zigbee to establish a new, more secure and interoperable IoT standard may be a hopeful sign that the Wild West era of ill-considered experimentation in IoT is coming to an end – or it may be a well-intentioned standard that simply ends up gathering dust on a shelf in Cupertino.

Turn up the heating, I’m freezing!

I’m sorry Dave, I can’t let you do that.

Regardless, don’t buy any devices that are too smart for their own good – or more importantly, yours. If there is no good reason for a thing to be "smart", then stick to the dumb version: it no doubt works better today, and won’t be obsolete tomorrow when the vendor goes out of business or simply terminates support for that product line.