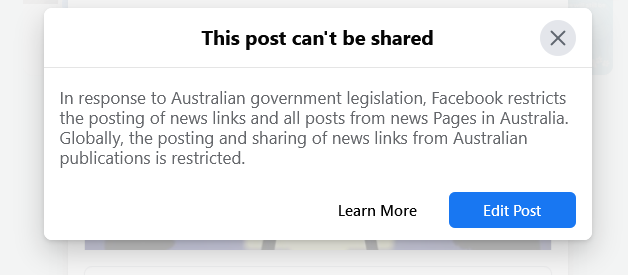

Google and Facebook have been feuding with the Australian government for a while, because in our cyberpunk present, that's what happens: transnational megacorporations go toe-to-toe with governments. The news today is that Google capitulated, and will pay a fee to continue accessing Australian news, while Facebook very much did not capitulate. This is what users are faced with, whether sharing a news item from an Australian source, or sharing an international source into Australia:

I see a lot of analysis and commentary around this issue that is simply factually wrong, so here's a quick explainer. Google first, because I think it's actually the more interesting of the two.

The best way to influence the outcome of an argument is to apply the right framing from the beginning. If you can get that framing accepted by other parties — opponents, referees, and bystanders in the court of public opinion — you’re home free. For a while there, it looked like Google had succeeded in getting their framing accepted, and in the longer run, that may still be enough of a win for them.

The problem that news media have with Google is not with whether or not Google links to their websites. After all, 95% of Australian search traffic goes to Google, so that’s the way to acquire readers. The idea is that Google users search for some topic that’s in the news, click through to a news article, and there they are, on the newspaper’s website, being served the newspaper’s ads.

The difficulty arises if Google does not send the readers through to the newspaper’s own site, but instead displays the text of the article in a snippet on its own site. Those readers do not click through to the newspaper’s site, do not get served ads by the newspaper, and do not click around to other pages on the newspaper’s site. In fact, as far as the newspaper is concerned, those readers are entirely invisible, not even counted as immaterial visitors to swell their market penetration data.

This scenario is not some far-fetched hypothetical; this exact sequence of events played out with a site called CelebrityNetWorth. The site was founded on the basis that people would want to know how rich a given famous person was, and all was well — until Google decided that, instead of sending searches on to CelebrityNetWorth, they would display the data themselves, directly in Google. CelebrityNetWorth's traffic cratered, together with their ad revenue.

That is the scenario that news media want to avoid.

Facebook does the same sort of thing, displaying a preview of the article directly in the Facebook News Feed. However, the reason why Google have capitulated to Australia's demands and Facebook have not is that Facebook is actively trying to get out of dealing with news. It's simply more trouble than it's worth, netting them accusations from all quarters: they are eviscerating the news media, while also radicalising people by creating filter bubbles that only show a certain kind of news. I would not actually be surprised if they used the Australian situation as an experiment prior to phasing out news more generally (it's already only 4% of the News Feed, apparently).

There has also been some overreach on the Australian side, to be sure. In particular, early drafts of the bill would have required that tech companies give their news media partners 28 days’ notice before making any changes that would affect how users interact with their content.

The reason these algorithms important is that for many years websites — and news media sites are no exception — have had to dance to the whims of Facebook and Google's algorithms. In the early naive days of the web, you could describe your page by simply putting relevant tags in the META elements of the page source. Search engines would crawl and index these, and a search would find relevant pages. However, people being people, unscrupulous web site operators quickly began "tag stuffing", putting all sorts of tags in their pages that were not really relevant but would boost their search ranking.

And so began an arms race between search engines trying to produce better results for users, and "dark SEO" types trying to game the algorithm.

Then on top of that come social networks like Facebook, which track users' engagement with the platform and attempt to present users with content that will drive them to engage further. A simplistic (but not untrue) extrapolation is that inflammatory content does well in that environment because people will be driven to interact with it, share it, comment on it, and flame other commenters.

So we have legitimate websites (let's generously assume that all news media are legit) trying to figure out this constantly changing landscape, dancing to the platforms' whims. They have no insight into the workings of the algorithm; after all, nothing can be published without the scammers also taking advantage. Even the data that is provided is not trustworthy; famously, Facebook vastly over-inflated its video metrics, leading publications to "pivot to video", only to see little to no return on their investments. Some of us, of course, pointed out at the time that not everyone wants video — but publications desperate for any SEO edge went in big, and regretted it.

Who decides what we see? The promise of "new media" was that we would not be beholden to the whims of a handful of (pale, male and stale) newspaper editors. Instead, we now have a situation in which it is not even clear what is news and what is not, with everybody — users and platforms — second-guessing each other.

And so we find ourselves running an experiment in Australia: is it possible to make news pay? Or will users not miss it once it's gone? Either way, it's going to be interesting. For now, the only big loser seems to be Bing, who had hoped to swoop in and take the Australian web search market from Google. The deal Google signed with News Corporation runs for three years, which should be enough time to see some results.

🖼️ Photo by Markus Winkler on Unsplash