The Changing Value Of Mistakes

The simplest possible definition of experience would equate it to mistakes. In other words, experience means having made many mistakes — and with any luck, learned from them.

This transubstantiation of mistakes into experience does rely on one hidden assumption, though, which is that the environment does not change too much. Experience is only valid as long as the environment in which the mistakes are made remains fairly similar to the current one. If the environment changes enough, the experience learned from those mistakes becomes obsolete, and new mistakes need to be made in the changed conditions in order to build up experience that is valid in that situation.

This reflection is important because there is a cultural misunderstanding of Ops and SRE that I see over and over — twice just this morning, hence this post.

I Come Not To Bury Ops, But To Praise It

Criticising Ops people for timidity or lack of courage because they are unwilling to introduce change into the environment they are responsible for is to miss that they have a built-in cultural bias towards stability. Their role is as advocates against risk — and change is inherently risky. Ops people made mistakes as juniors, preferably but not always in test environments, and would rather not throw out all that hard-earned experience to start making mistakes all over again. The ultimate Ops nightmare is to do something that turns your employer into front-page news.1

If you’re selling or marketing a product that requires Ops buy-in, you need to approach that audience with an understanding of their mindset. Get Ops on-side by de-risking your proposal, which includes helping them to understand it to a point where they are comfortable with it.

And don’t expect them to be proactive on your behalf; the best you can expect is permission and maybe an introduction. On the other hand, they will be extremely credible champions after your proposal goes into production — assuming, of course, that it does what you claim it does!

Let's break down how that process plays out.

Moving On From The Way Things Were Always Done

A stable, mature way of doing things is widely accepted and deployed. The team in charge of it understand it intimately — both how it works, and crucially, how it fails. Understanding the failure modes of a system is key to diagnosing inevitable failures quickly, after all, as well as to mitigating their impact.

A new alternative emerges that may be better, but is not proven yet. The experts in the existing system scoff at the limitations of the new system, and refuse to adopt it until forced to.

On the one hand, this is a healthy mechanism. It’s not a good idea to go undermining something that’s working just to jump on the latest bandwagon. When you already have something in place that does what you need it to do, anyone suggesting changes has got to promise big benefits, and ideally bring some proof too. The Ops team are not (just) being curmudgeonly stick-in-the-muds; you are asking them to devalue a lot of their hard-won experience and expose themselves to mistakes while they learn the new system. You have to bring a lot of value, and prove your promises too, in order to make that trade-off worth their while.

The problem is when this healthy immune response is taken too far, and the resistance continues even once the new approach has proven itself. Excessive resistance to change leads inevitably downwards into obsolescence and stasis. There's an old joke in IT circles that the system is perfect, if it weren't for all those pesky users. After all, every failure involves user action, so it follows logically that if only there were no users, there would be no failures — right? Unfortunately a system without users is also not particularly useful.

The reason why resistance to change can continue too long is precisely because the Ops' team's experience is the product of mistakes made over time. With each mistake that we make, we learn to avoid that particular mistake in the future. The experience that we gain this way is valuable precisely because it means that we are not constantly making mistakes – or at least, not the same obvious ones.

Learning By Making Mistakes

When I was still a wet-behind-the-ears sysadmin, I took the case off a running server to check something. I was used to PC-class hardware, where this sort of thing is not an issue. This time however, the whole machine shut down very abruptly, and the senior admin was not happy to have to spend a chunk of his time recovering the various databases that had been running on that machine. On the plus side, I never did it again…

We look for experts to run critical systems precisely because they have made mistakes elsewhere, earlier in their careers, and know to avoid them now. If we take an expert in one system and sit them down in front of a different system, however, they will have to make those early mistakes all over again before they can build their expertise back up.

Change devalues expertise because it creates scope for new mistakes that have not been experienced before, and which people have not yet learned to avoid.

Run The Book

Ops teams build runbooks for known situations. These are distillations of the team's experience, so that if a particular situation occurs, whoever is there when it all goes down does not have to start their diagnosis from first principles. They also don't need to call up the one lone expert on that particular system or component. Instead, they can rely on the runbook.

Historically, a runbook would have been a literal book: a big binder with printed instructions for all sorts of situations. These days, those instructions are probably automated scripts, but the idea is the same: the runbook is based on the experience of the team and their understanding of the system, and if the system changes enough, the runbook will have to be thrown out and re-written from scratch.

So how to square this circle and enable adoption of new approaches in a safe way that does not compromise the stability of running systems?

Make Small Mistakes

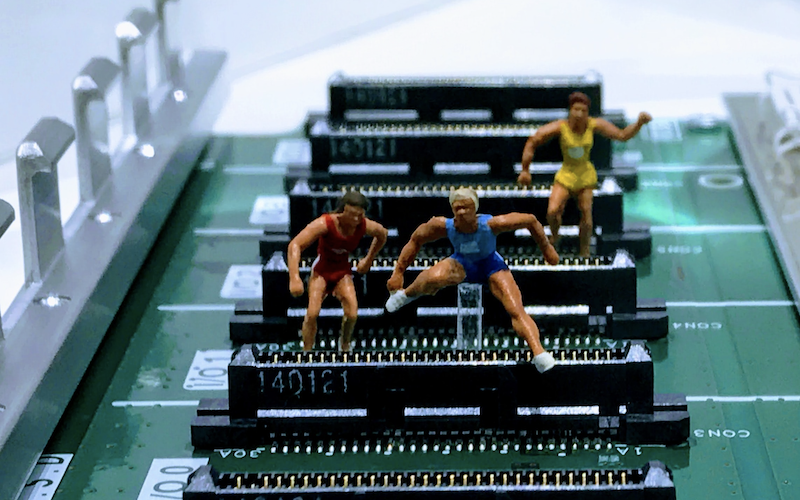

The best approach these days centres on agility, working around many small projects rather than single big-bang multi-year monsters. This agile approach enables mistakes to be made – and learned from – on a small scale, with limited consequences. The idea is to limit the blast radius of those mistakes, building experience before moving up to the big business-critical systems that absolutely cannot fail.

New technologies and processes these days embrace this agility, enabling that staged adoption with easy self-serve evaluations, small starting commitments, and consumption-based models. This way, people can try out the new proposed approaches, understand what benefits they offer, and make their own decisions about when to make a more wholesale move to a new system.

Small Mistakes Enable Big Changes

The positive consequences of this piecemeal approach are not just limited to the intrinsic benefits of the new system – faster, easier, cheaper, or some combination of the three. There are also indirect benefits: by working with cutting-edge systems instead of old legacy technology, it will also become easier to recruit people who are eager to develop their own careers. Old systems are harder to make new mistakes in, so it's also harder to build experience. Lots of experts in mature technologies have already maxed out their XP and are camping the top rungs of the career ladder, so there's not much scope for growth there — but large-scale change resets the game.

On top of that, technological agility leads to organisation agility. These days, processes are implemented in software, and the speed with which software can move is a very large component in the delivery of new offerings. Any increase in the agility of IT delivery is directly connected to an increase in business agility – launching new offerings faster, expending more quickly into new markets, responding to changing conditions.

Those business benefits also change the technological calculus: when all the mainframe did was billing, that was important, but doing it a little bit better than the next firm was not a game-changer. When software is literally running the entire business, even a small percentage increase in speed and agility there maps to major business-level differentiation.

Experience is learning from mistakes, but if the environment changes, new mistakes have to be made in order to learn. Agile processes and systems help minimise the impact of those changes, delivering the benefits of constant evolution.

Stasis on the technology side leads to stasis in the organisation. Don’t let natural caution turn into resistance to change for its own sake.

🖼️ Photos by Daniela Holzer, Varvara Grabova, Sear Greyson and John Cameron on Unsplash

-

On the other hand, blaming such front-page news on "human error" is also a cop-out. Major failures are not the fault of an individual operator who fat-fingered one command: they are the ultimate outcome of strategic failures in process and system design that enabled that one mistake to have such strategic consequences. ↩