Faster disruption

There are theories which seem just intrinsically right when you hear them. Clayton Christensen's famous "disruption theory" is one of these. I was recommended to read "The Innovator's Solution" by a friend of mine who had previously worked directly with Professor Christensen, and it definitely shaped my thinking about the technology business.

When the core business approaches maturity and investors demand new growth, executives develop seemingly sensible strategies to generate it. Although they invest aggressively, their plans fail to create the needed growth fast enough; investors hammer the stock; management is sacked; and Wall Street rewards the new executive team for simply restoring the status quo ante: a profitable but low-growth core business.

In sustaining circumstances—when the race entails making better products that can be sold for more money to attractive customers—we found that incumbents almost always prevail. In disruptive circumstances—when the challenge is to commercialise a simpler, more convenient product that sells for less money and appeals to a new or unattractive customer set—the entrants are likely to beat the incumbents.

Disruption theory explains a lot about many markets, although it is not without its critics. In particular, Jill Lepore caused a minor furore with a piece in the New Yorker entitled The Disruption Machine, in which she accused Professor Christensen of cherry-picking his evidence.

There is one famous exception and objection to disruption theory, and that is Apple. According to the orthodox version of the theory, Apple should have been disintermediated by now by smaller, more agile modularised competitors. Every year seems to bring its candidate as the disruptor of Apple: whether it's the Nexus, or Samsung, or Xiaomi, or whoever. Apple somehow survives them all, and not just survives, but goes from strength to strength.

Why is this?

Ben Thompson wrote about how classic disruption theory applies mainly to enterprise products, where the buyer is not the user, and so "feeds & speeds" that can be mapped on a checklist rule the purchasing process. The buyer is looking for a product that can satisfy some simplified criteria. Beyond that binary fit, the decision is primarily based on price.

Apple emphatically does not fit this model, with its focus on design and the user experience. The buyer is the user, and once their basic criteria are met, they can still be swayed by different user experience and personal preferences - of course, up to the budget they have available or are willing to assign to a piace of electronics. Therefore, Apple continues to be able to command much higher prices for devices that are - on paper - comparable to their modularised competitors. Users return again and again for newer versions of their device, every year or two, and Apple's profit margins are legendary.

Enterprise software had always seemed to be on a much more classic track to disruption, with procurement departments working from Request for Proposal (RfP) documents that generally allow yes/no or at most grading on a short scale, typically from one to four. Recently, though, the market has been changing, and incumbent vendors are being disrupted by offerings which bypass the traditional buyer in Procurement and appeal directly to the end user. One model is open-source, where sufficiently technical users have been able to download and use free software without support from central IT for at least the last fifteen years. The main roadblock to this avenue of disruption was in users' willingness to futz around with graphics drivers or whatever. More recently, a new avenue has opened up, namely software as a service. SaaS offerings require much less technical acumen, and much less effort even when the technical acumen is available. Even users who are able and willing to get their hands dirty only have a limited amount of time available to do so, and are quite happy to hand the responsibility off to someone else.

This is how you get the infamous "shadow IT" - enterprise IT's particular incarnation of disruption theory. However, I do wonder whether enterprise software might not also have exceptions to classic disruption theory. Buyer inertia may prevent modularisation, or at least complete modularisation, from taking hold, or delay it for a long time.

From integrated to modular to orchestrated

Apple cannot easily be replaced by modular competitors, even when those competitors offer lower prices and nominally higher performance, because the overall user experience delivered by those competing devices is inferior. There is an equivalent mechanism in enterprise software - although, unfortunately, it does not often manifest in attractive user interfaces and satisfying interactions. Rather, it is the experience of the buyer which is important.

Many mature, established companies have a "vendor rationalisation" initiative of some sort. Some may even go so far as to have an "Office of Vendor Management" or equivalent. One way of looking at this is the "one throat to choke" school of thought taken to its extreme, but there is something else going on here.

As software becomes more complex, and user requirements more varied, there are fewer and fewer one-stop software packages. Even within a single vendor's offerings, users will need to select multiple packages, many of which will have been developed by different teams or even by different companies acquired by the vendor over the years. Customers are looking for a trade-off between best-of-breed solutions from different vendors or open-source tools that require substantial work to integrate with each other, versus vertically integrated solutions from a single vendor that may not excel in any one area but can deliver on the whole task.

The variable that will drive choice in one direction or the other is the rate of change. If the integration between the best-of-breed packages remains valid, once developed, for a significant length of time, then the modularised, disrupting solutions - whether commercial on-premise, open-source, or SaaS - will win. If on the other hand integration is a constant effort that never fully stabilises, requiring never-ending development to chase a constantly moving target, then the benefits of the pre-integrated solution become more attractive in their turn.

Timing is everything

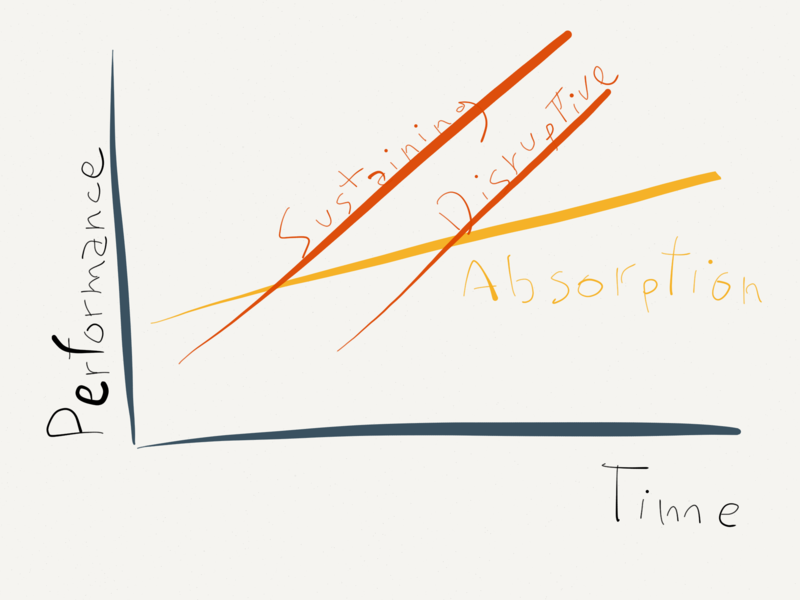

The twist is in the incentives. Developers of the modularised solutions are in a race with other modularised solutions, hired to do the same job, in Christensen's terminology. The way they keep ahead in the race is by evolving faster, adding more functionality sooner than their competitors. They have no direct incentive to stabilise their solutions. For the same reason, they have no particular incentive to stabilise the interfaces to their solutions, as this makes them more easily replaceable by their competitors (less sticky).

The upshot of all this is that a vertically-integrated company can stay ahead of the curve of disruption by innovating just enough to maintain stability for its users, while supporting a certain speed of evolution. This is the job that their customers hire them to do.

The commercial Unix platforms were displaced by Linux because both followed standards (GNU, Posix, and so on) that made them largely fungible from the point of view of their buyers, once Linux had developed beyond its beginnings. iPhones were not displaced by Android phones because they were not fungible to their buyers.

How not to be fungible

What are the characteristics of enterprise software that can make it non-fungible? Simply put, it comes pre-integrated, both with itself (or rather, between different components of itself) and with everything else. This is why content is so important. An API is not enough to avoid being disrupted; any open-source project worth its salt comes with an API - probably RESTful these days, but the principle is independent of technology. What prevents disruption, making the software "sticky", is content: pre-built integrations, workflows, best practices, and data transformations, that make the software work seamlessly for customers' needs.

Enterprise software needs enterprise-grade content that takes advantage of those integrations. Relying on technical capabilities alone leaves enormous vulnerability to motivated developers and agile start-ups. A would-be enterprise vendor must focus on what it can do to prevent disruption. Agility - chasing the bleeding edge - is not the job that buyers hire it to do.

However, there ain't no such thing as a free lunch: those integrations have to keep up with those other fast-moving targets. There is no "we support these two products, and we will add the third-placed platform with the next release of our software in a year's time"1. The integrations themselves have to evolve, and do so in a way that is both backwards-compatible (you can't break everything your users have built every time you upgrade) and fast-moving (you have to keep up with where your users are going, whether to new platforms, or to new versions of existing platforms2).

The bottom line

All of this represents yet another level of abstraction. The competition moves to a different layer of the stack: the content and integrations. Enterprise vendors who refuse to follow along are simply ceding to their competition; users - and importantly, buyers - are there already.

Hardware got commoditised, then operating systems got commoditised, and now it's the next layer up. It's not what you have under the hood, it's what you do with it - and both people and enterprises will buy the tool that enables them to get the most done.

-

Please note the small print around any roadmap estimates. ↩

-

Note that saying "nobody is using X in production yet" doesn't cut it. Users are most certainly using X in testing as a prelude to putting it into production, and as a part of that process they need to test that everything else integrates with X. Missing that wave is the first step to hearing "we went into production with your competitor on all new projects because they were able to support us in our move to X". ↩