AI and machine-learning (ML) are the hot topic of the day. As is usually the case when something is on the way up to the Peak of Inflated Expectations, wild proclamations abound of how this technology is going to either doom or save us all. Going on past experience, the results will probably be more mundane – it will be useful in some situations, less so in others, and may be harmful where actively misused or negligently implemented. However, it can be hard to see that stable future from inside the whirlwind.

Uhoh, This content has sprouted legs and trotted off.

In that vein, I was reading an interesting article which gets a lot right, but falls down by conflating two issues which, while related, should remain distinct.

there’s a core problem with this technology, whether it’s being used in social media or for the Mars rover: The programmers that built it don’t know why AI makes one decision over another.

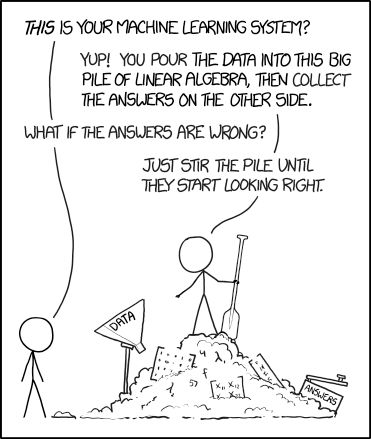

The black-box nature of AI comes with the territory. The whole point is that, instead of having to write extensive sets of deterministic rules (IF this THEN that ELSE whatever) to cover every possible contingency, you feed data to the system and get results back. Instead of building rules, you train the system by telling it which results are good and which are not, until it starts being able to identify good results on its own.

This is great, as developing those rules is time-consuming and not exactly riveting, and maintaining them over time is even worse. There is a downside, though, in that rules are easy to debug. If you want to know why something happened, you can step through execution one instruction at a time, set breakpoints so that you can dig into what is going on at a precise moment in time, and generally have a good mechanical understanding of how the system works - or how it is failing.

I spend a fair amount of my time at work dealing with prospective customers of our own machine-learning solution. There are two common objections I hear, which fall at opposite ends of the same spectrum, but both illustrate just how different users find these new techniques.

Yes, there is an XKCD for every occasion

The first group of doubters ask to "see the machine learning". Whatever results are presented are dismissed as "just statistics". This is a common problem in AI research, where there is a general public perception of a lack of progress over the last fifty years. It is certainly true that some of the overly-optimistic predictions by the likes of Marvin Minsky have not worked out in practice, but there have been a number of successes over the years. The problem is that each time, the definition of AI has been updated to exclude the recent achievement.

Something of the calibre of Siri or Alexa would absolutely have been considered AI, but now their failure to understand exactly what is meant in every situation is considered to mean that they are not AI. Certainly Siri is not conscious in any way, just a smart collection of responses, but neither is it entirely deterministic in the way that something like Eliza is.1

This leads us to the second class of objection: "how can I debug it?" People want to be able to pause execution and inspect the state of variables, or to have some sort of log that explains exactly the decision tree that led to a certain outcome. Unfortunately machine learning simply does not work that way. Its results are what they are, and the only way to influence them is to flag which are good and which are bad.

This is where the confusion I mentioned above comes in. When these techniques are applied in a purely technical domain - in my case, enterprise IT infrastructure - the results are fairly value-neutral. If a monitoring event gets mis-classified, the nature of Big Data (yay! even more buzzwords!) means that the overall issue it is a symptom of will probably still be caught, because enough other related events will be classified correctly. If however the object of mis-categorisation happens to be a human being, then even one failure could affect that person’s job prospects, romantic success, or even their criminal record.

The black-box nature of AI & ML is where very great care must be taken to ensure that ML is a safe and useful technique to use in each case, in legal matters especially. The code of law is about as deterministic as it is possible to be; edge cases tend to get worked out in litigation, but the code itself generally aims for clarity. It is also mostly easy to debug: the points of law behind a judicial decision are documented and available for review.

None of these constraints apply to ML. If a faulty facial-recognition algorithm places you at the heart of a riot, it’s going to be tough to explain to your spouse or boss why you are being hauled off in handcuffs. Even if your name is ultimately cleared, there may still be long-term damage done, to your reputation or perhaps to your front door.

It’s important to note that, despite the potential for draconian consequences, the law is actually in some ways a best case. If an algorithm kicks you off Google and all its ancillary services (or Facebook or LinkedIn or whatever your business relies on), good luck getting that decision reviewed, certainly in any sort of timely manner.

The main fear that we should have when it comes to AI is not "what if it works and tries to enslave us all", but "what if it doesn’t work but gets used anyway".

Photo by Ricardo Gomez Angel via Unsplash

-

Yes, it is noticeable that all of these personifications of AI just happen to be female. ↩